Wright Morris (1910-98), the famous US novelist but little-known photographer, who is about to have a major posthumous survey at Fotografiemuseum Amsterdam (Foam), wrote in his semi-autobiographical book The Territory Ahead (1958): “Life, raw life, the kind we lead every day… has the curious property of not seeming real enough.”

Whilst Morris’s art succeeded in elevating reality, his actual life did not lack for drama. Morris was born in Central City, Nebraska. His mother died six days after he was born, so he was raised by a stepmother who, in his words, “was closer to my age than to my father’s”. They moved frequently as his father searched for work. Each summer, he would labour as a farmhand for his uncle in the midst of dust bowl America. “He didn’t have a stable home, he never had a mother figure. I think he started to wonder: ‘Who am I? Where am I from?’” says the exhibition curator, Hinde Haest.

Morris, then, was not a poverty tourist. He lived what he photographed. Decades before such phrases became current in photographic discourse, Morris’s images were actively authored, relational and self-conscious.

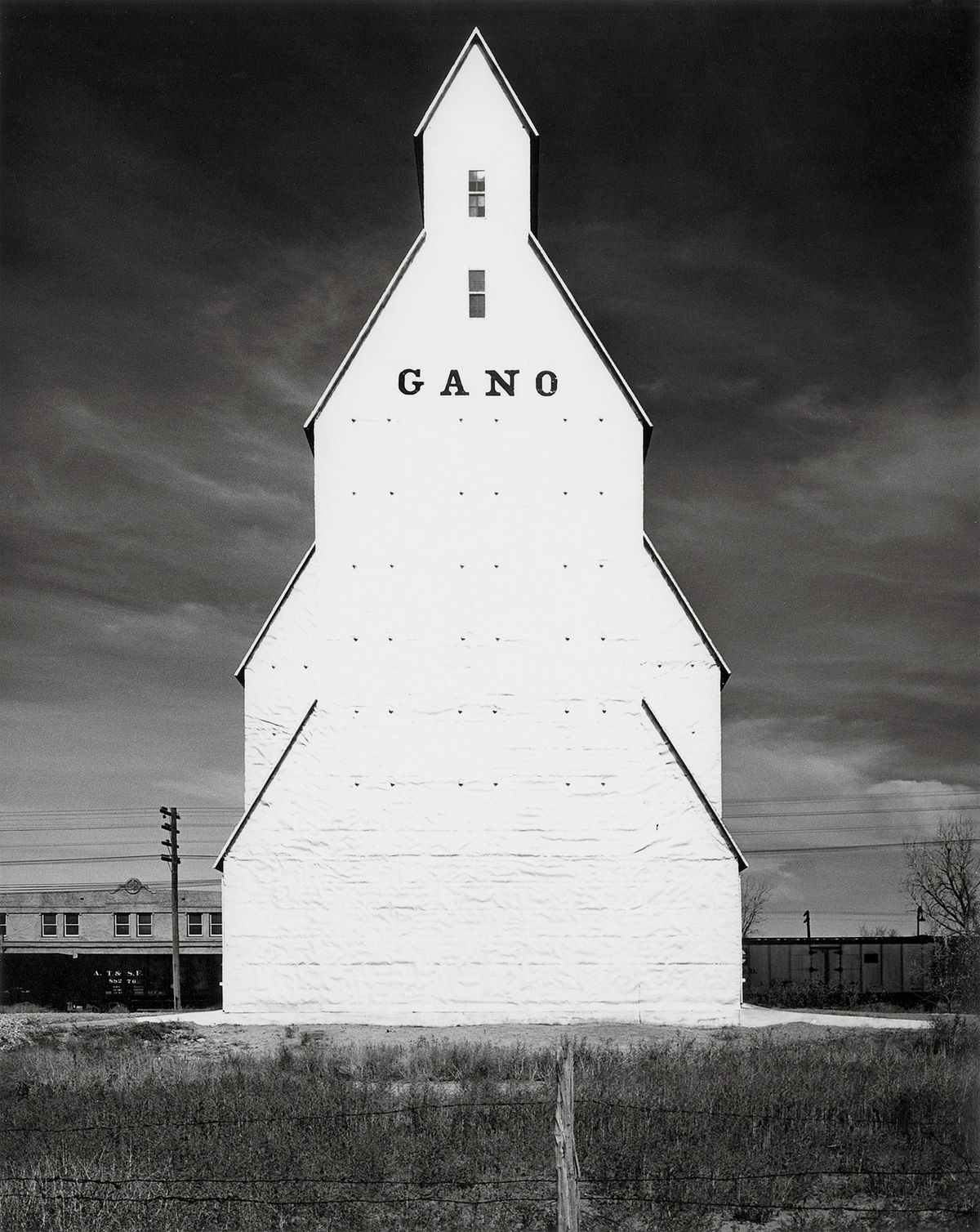

Wright Morris's Tombstone, Arizona (1940) © Estate of Wright Morris

“His work is unique for the era,” Haest says. “He was from Nebraska, he was from a dirt farm; his images weren’t a documentary endeavour. They were a search for his roots.”

As he grew older, Morris started to become estranged from his father, and, at the age of 23, he left Nebraska in search of something more real. Without anything in the way of money, Morris managed to hoodwink his way to Europe, where, by his own account, he spent a year “wandering”. Walking around Europe inspired a craving for a nomadic lifestyle, and on his return to the US, Morris travelled across the Great Plains, eventually settling in California, where he lived until his death in 1998.

“He saw weathered objects as having a bodily imprint, of being more of a portrait than a face”

Throughout his US travels, Morris became a contemporary of fellow road-trippers who became the renowned documentarians of the country’s Great Depression: Walker Evans and Dorothea Lange. “I think Wright Morris’s work is on par with those great photographers—[but] they have gone on to become iconic, and Wright Morris has not,” Haest says. “Yet he takes a very different and much more authored approach.”

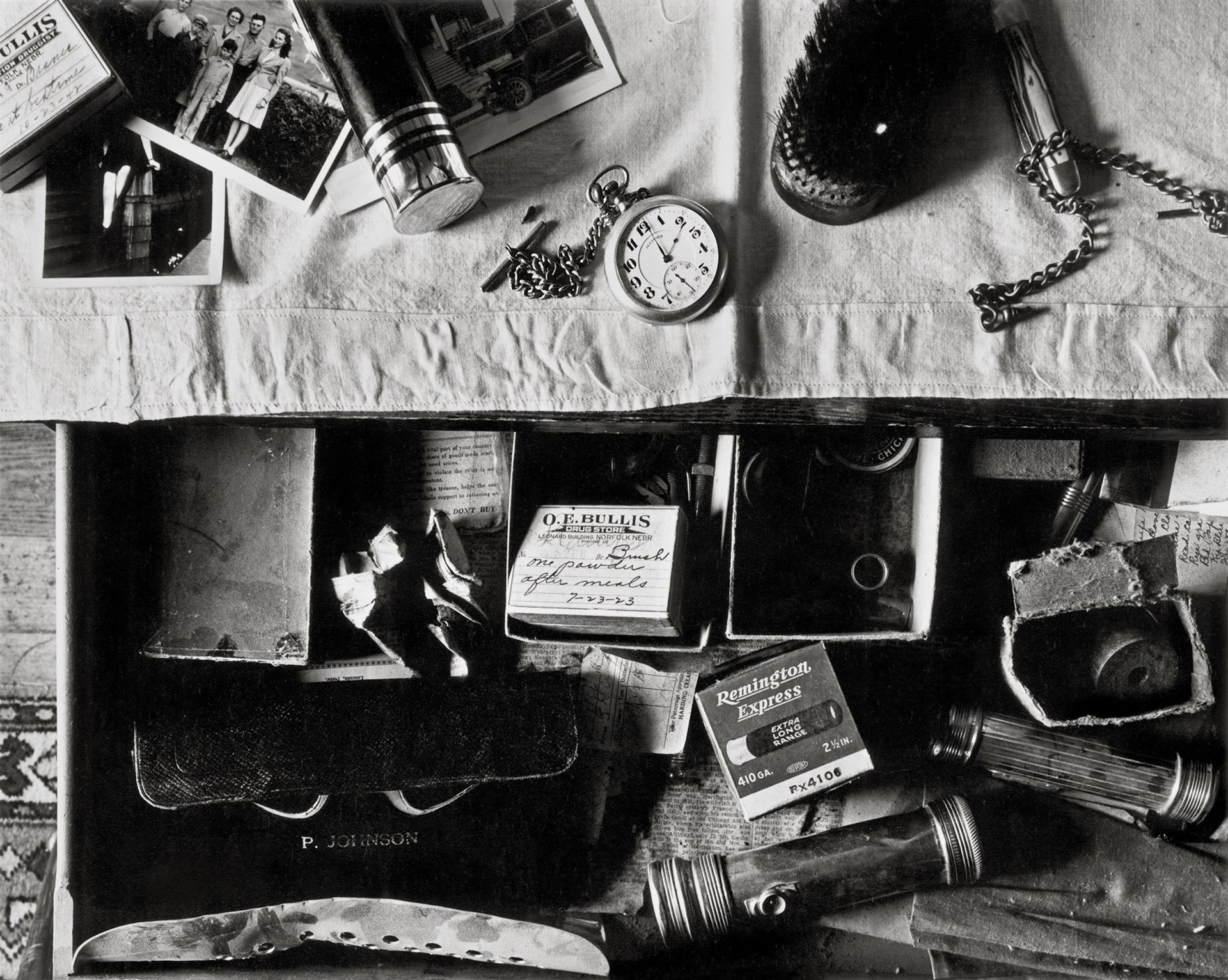

The death of Morris’s father inspired his return to Nebraska—and an incredibly fertile artistic period followed. His images from this time are characterised by themes of abandonment. He photographed empty domestic spaces and discarded objects—rusting farm equipment, old shoes, ragged clothes, moulding beds—that bore the imprint of their former owner. “He believed that a photograph of a chair, or a bed, or farm machinery, told you more about its owner than any other image,” Haest says. “He saw these weathered objects as having a bodily imprint, of being more of a portrait than a face.”

Wright Morris's Dresser Drawer (1947) © Estate of Wright Morris

In The Home Place, a “photo-text” that will feature in the exhibition, Morris wrote: “What is it that stirs you about a vacant house? I supposed it has something to do with the fact that any house that’s been lived in, any room that’s been slept in, is not vacant anymore.”

Many of the images taken during this productive time in his life will be on show at Foam. “He spent his whole life trying to recover his own past,” Haest says. “Sometimes he would make things up—his memory and his imagination seemed to intertwine. He seemed to be searching for a fiction that might become his new reality; a reconstruction of his childhood. It was a search for his identity, and an attempt to reconcile his life with himself.”

The exhibition is sponsored by the Terra Foundation for American Art.

• Wright Morris: the Home Place, Fotografiemuseum (Foam), Amsterdam, 24 January-5 April