During the summer of 1955 in the south of France, Pablo Picasso was filmed boldly sketching flowers that morph into a fish, then a cockerel, before finally using ink to colour the picture and transform the bird’s body into the head of a faun. This fluid creative process was captured in Henri-Georges Clouzot’s experimental film Le Mystère Picasso (1956), which aimed to portray the artist at work.

“They devised this quite ingenious technique so that Clouzot could actually film Picasso in the act of painting and drawing,” says Ann Dumas, the co-curator of Picasso and Paper, which opens on 25 January at the Royal Academy of Arts in London. Two recently restored drawings and a huge collage from Le Mystère Picasso will feature in the exhibition, which explores the myriad ways the artist used paper throughout his long career.

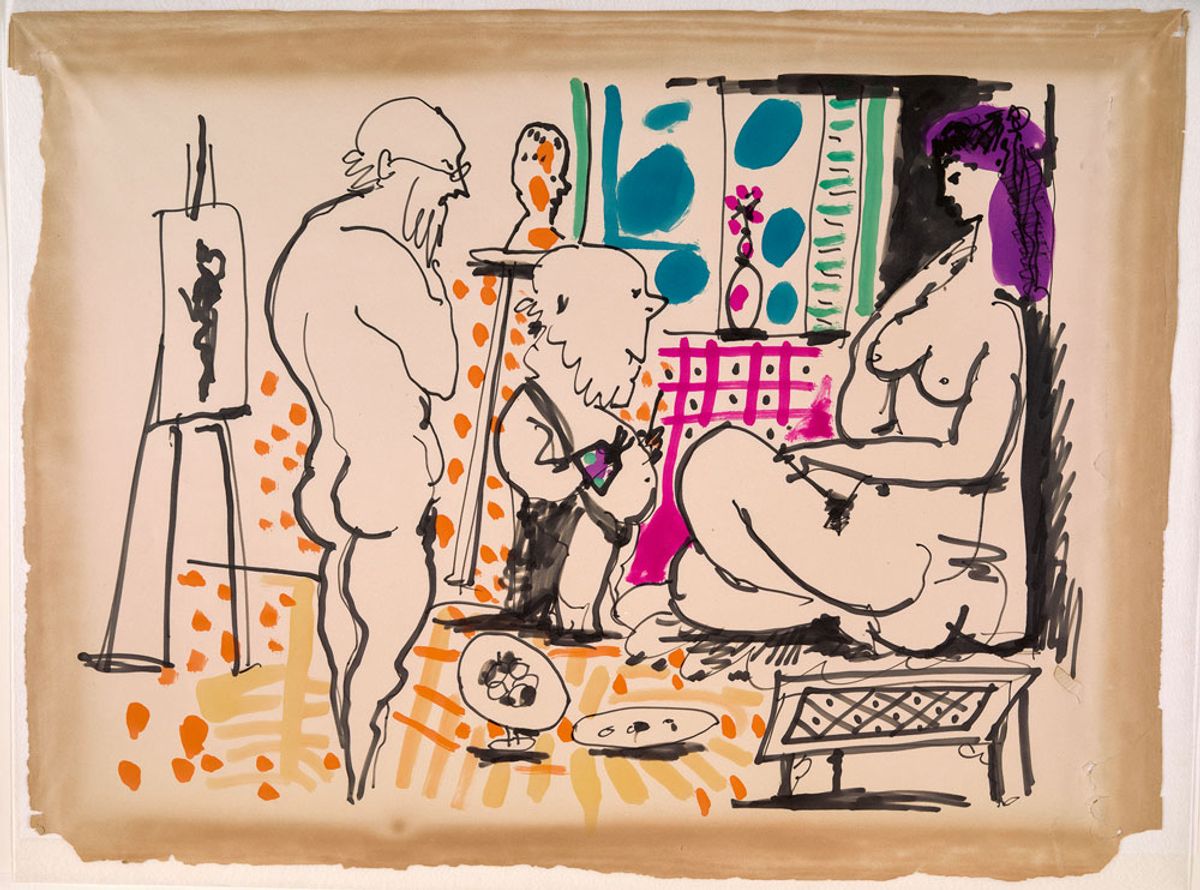

For the making of the film, newsprint paper was stretched on an easel, with the artist drawing on one side and the camera filming on the other as the ink bled through. “One reason they were able to do it was that Picasso had started using felt tip pens, which were a novelty at the time and were being imported from America,” Dumas says. “The strong colour seeped into this blank newsprint paper but didn’t drip.”

Clouzot combined stop-motion and time-lapse photography “so the images that Picasso created appear before our eyes as if by magic”, Dumas says. “It’s as if the cinema screen becomes his canvas.” The filmmaker was aided by the cinematographer Claude Renoir, the nephew of the famous director Jean Renoir and grandson of one of Picasso’s favourite artists, Pierre-Auguste Renoir.

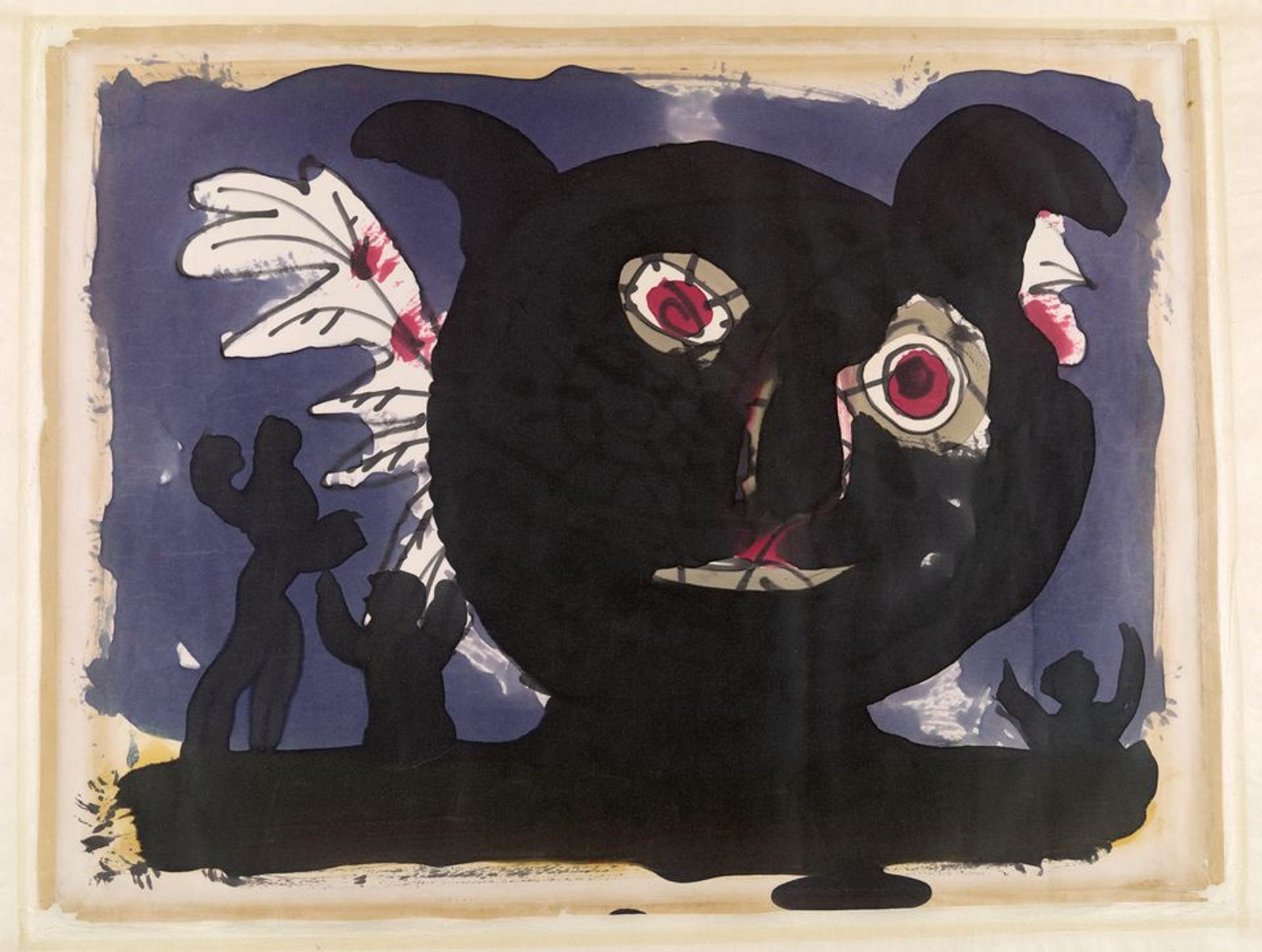

Picasso's Visage: Head of a Faun (1955) was created in Nice for the film Le Mystère Picasso Musée national Picasso-Paris; © Succession Picasso/DACS; photo: Adrien Didierjean/RMN, Grand Palais

Although most of the drawings from the film were destroyed, 39 remain in the collection of the Musée National Picasso-Paris, the main lender for the Royal Academy show. The Paris museum was founded to house Picasso’s personal art collection and archive upon his death. “Picasso would never throw anything away,” Dumas says. One section of the exhibition will include examples of the paper ephemera he kept.

Two of the drawings from the film, In the Studio and Visage: Head of a Faun, have been especially restored for the exhibition. Although newsprint was perfect for the filming process, its tendency to tear and fade means that time has taken its toll on the works. “The lighting during filming has contributed to the chemical degradation of the newsprint, which is by nature unstable,” says the co-curator from the Musée Picasso-Paris, Emilia Philippot. “Many tears have appeared.”

Conservators removed the yellowed adhesive tape that had previously been used to fix the tears in the newsprint, as well as the Japanese backing paper added to shore up the delicate newsprint. The removal of the backing paper means that the drawings can now be viewed from both sides, as originally intended, and therefore regain their “specific identity”, Philippot says. The museum has also worked with picture framers to display the newly restored works recto and verso.

Of the 39 surviving newsprint works, eight have been restored in preparation for exhibitions with support from the host institutions. One appeared at the Musée Masséna in Nice last summer, and another four will go on show this spring in the exhibition Picasso: the Bathers (18 March-3 July) at the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Lyon. The restoration of the two drawings coming to London was also supported by the Cleveland Museum of Art, where the Picasso and Paper show will travel in May.

The Royal Academy will screen clips from Le Mystère Picasso in the same gallery as the newsprint drawings and the large collage Reclining Nude Woman (1955), a portrait of Picasso’s second wife Jacqueline Roque that the artist made for Clouzot’s film using wallpaper and woven paper tacked on canvas.

• Picasso and Paper, Royal Academy of Arts, London, 25 January-13 April; Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland, 24 May-23 August