Vincent van Gogh is always said to have failed to sell his paintings during his lifetime, but a letter appears to record the sale of a self-portrait to two London dealers. No such painting is known, but it is just possible that it might survive, unrecognised as a work by the Dutch master.

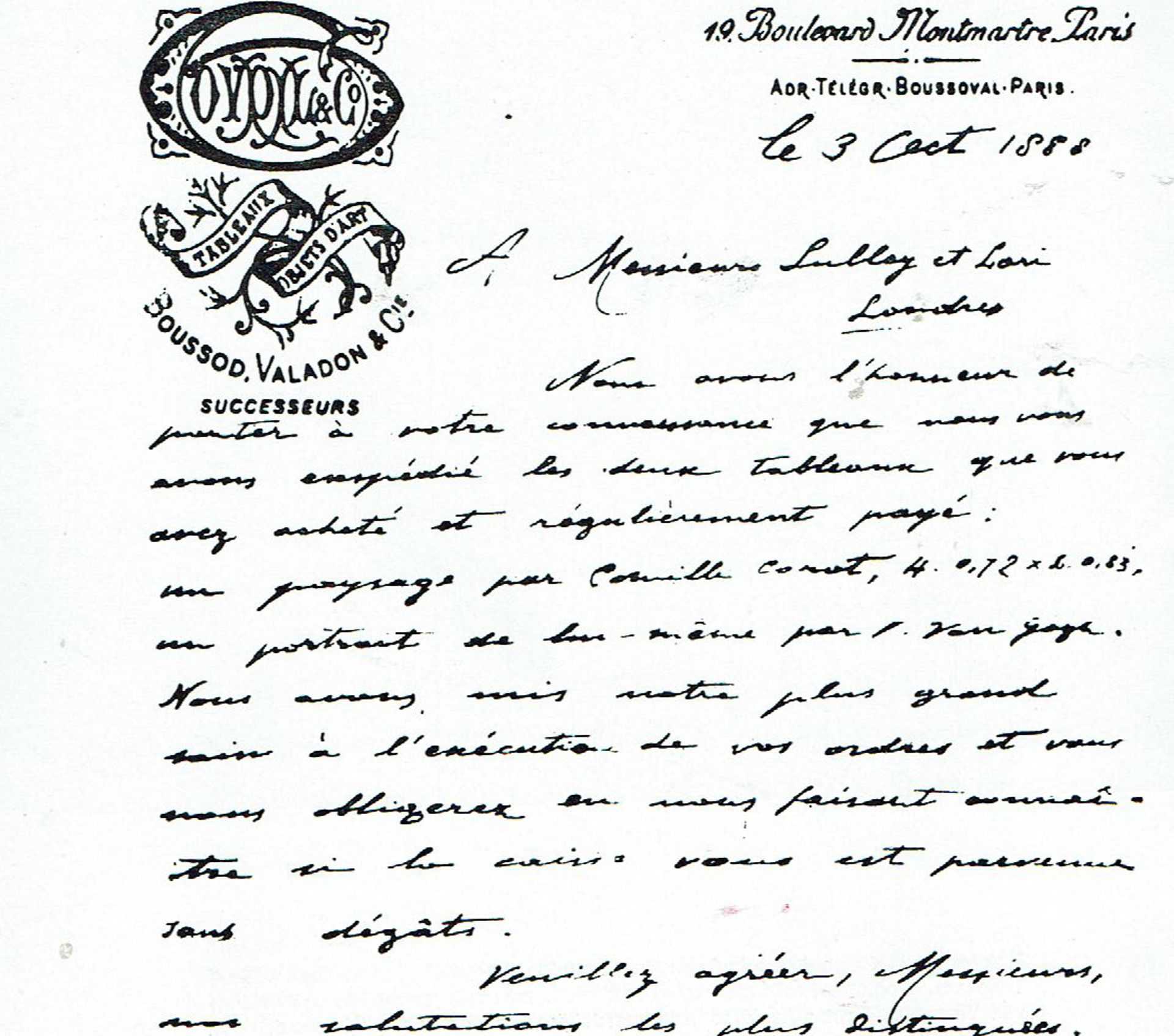

The letter recording the sale was written by Vincent’s brother Theo, who was a dealer at the Goupil gallery (also known as Boussod, Valadon & Cie) in Paris. Dated 3 October 1888, when Vincent was living in the Yellow House in Arles, it says (in translation): “We have the honour to inform you that we have sent you the two pictures you have bought and duly paid for: a landscape by Camille Corot, H [height] 0.72 x W [width] 0.83, and a self-portrait by V. van Gogh. We have put our greatest care into the execution of your orders and would be grateful if you could let us know if the box has arrived safely.”

Letter from Theo van Gogh to “Messieurs Sulley et Lori/Londres”, 3 October 1888 Published in Tralbaut, De Gebroeders Van Gogh, Uitgave van het Gemeentebestuur, Zundert, 1964, p186

This letter was reproduced in a relatively obscure Dutch book on Van Gogh, published in 1964 by the distinguished Belgian specialist on the artist, M.E. Tralbaut (who died in 1976). The location of the original letter remains a mystery.

It certainly comes as a surprise that Van Gogh succeeded in selling his first painting in 1888—and that it went to England, where his art remained relatively unappreciated until the early 1900s. So one’s immediate thought is that the letter might be a fake. But a detailed examination suggests that it is likely to be authentic.

The letter is on the headed gallery notepaper used by Theo and the handwriting appears to be his. However, without access to the original letter, it is impossible to authenticate the handwriting and be sure that the text has not been tampered with.

But what adds further credibility to the letter is that it is addressed to “Messieurs Sulley et Lori/London”. No such firm existed, but my research reveals that this must refer to two British dealers: Arthur Joseph Sulley (1853-1930) and William Duff Lawrie (1849-1909). Although the second name is misspelt by Paris-based Theo, Lawrie would be pronounced like Lori in French.

By the 1890s the two dealers were working together, with their gallery known as Lawrie & Company and specialising in modern French and Dutch art. Gallery records from Goupil and Lawrie show that both regularly handled Corot landscapes, although there is no trace of the two pictures named in the letter. No portraits of the two British dealers survive, but Lawrie’s wife Jessie was painted by the Scottish artist William McTaggart.

William McTaggart’s Portrait of Mrs William Lawrie (1881) Courtesy of National Galleries of Scotland. Presented by Madame Violante Lawrie, 1952. Photo: Antonia Reeve

If someone had set out to forge the 1888 letter about the Van Gogh self-portrait, it would be very curious that they would have misspelt Lawrie as Lori. This still leaves open the possibility that the text has been tampered with. But Tralbaut, an experienced Van Gogh specialist who was well versed in using archives and must have known about the source of the letter, wrote that handwriting experts had convinced him that the authenticity of the letter should “not be disputed” and the spacing of the words did not indicate any tampering.

Van Gogh’s own correspondence does not refer to the sale of a self-portrait, but there is a reference to another Parisian dealer who had been interested in acquiring his work, Athanase Bague. On 8 October 1888, only five days after Theo’s letter to Sulley and Lawrie, Vincent commented to his brother about Bague: “I’m very pleased that he’s bought this study”, but without identifying the subject of the painting. This suggests that Bague may have acted as some sort of agent for the London sale.

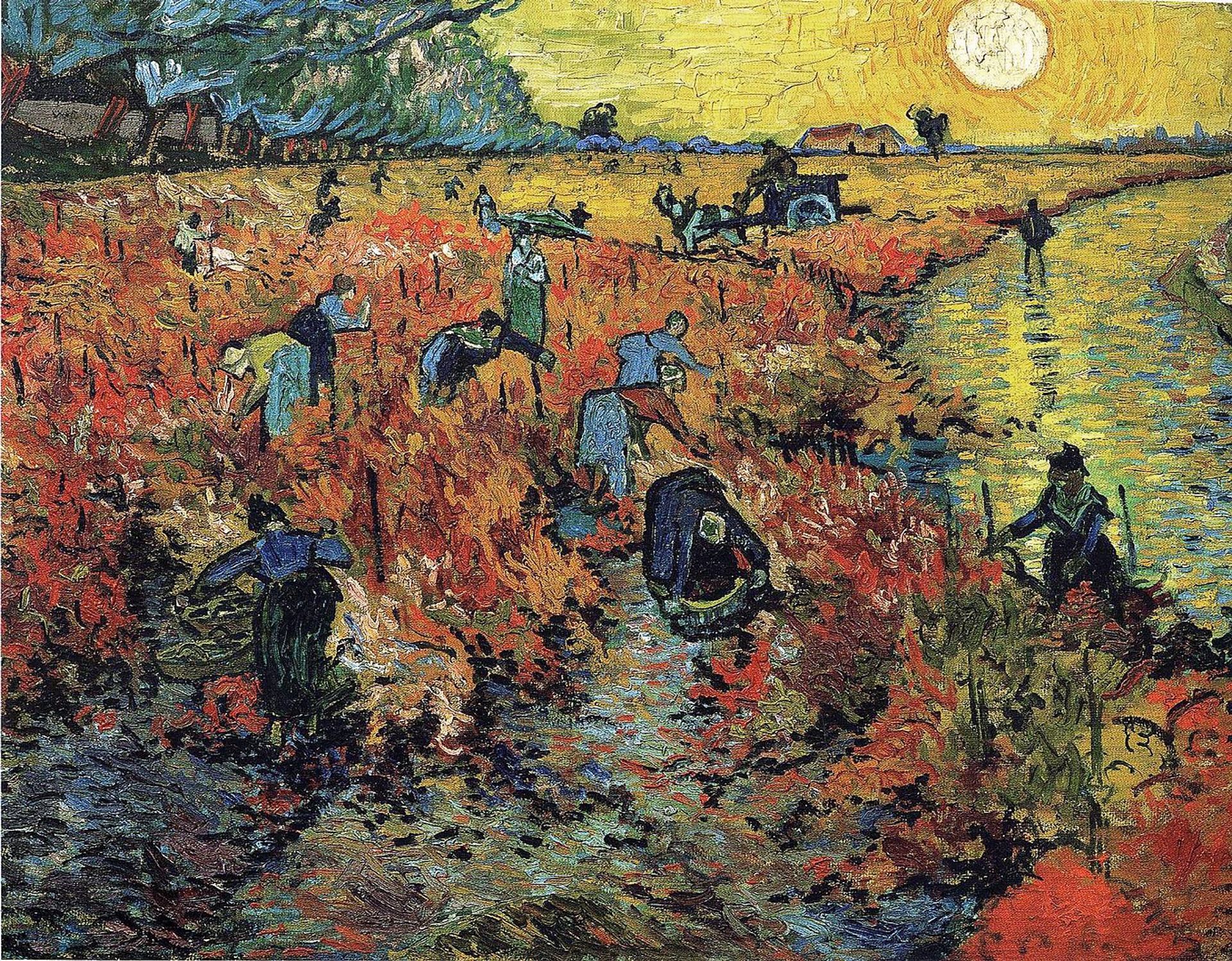

Vincent van Gogh’s The Red Vineyard (1888) Courtesy of the Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow

The only painting that Van Gogh is certain to have sold during his lifetime was The Red Vineyard, painted in Arles in 1888. Exhibited in Brussels in February 1890, it was bought by Anna Boch, a Belgian artist. If there was indeed an October 1888 sale, it suggests that Van Gogh was closer than we thought to winning commercial success during his own lifetime.

And as for the self-portrait, which may well have ended up with the two London dealers, it has disappeared without trace. There is a remote possibility that it survives, unrecognised as a work by one of the world’s greatest artists. Hopefully further publicity may cast more light on this most intriguing letter.