What a year of disruption. Not disruption in the tech PR speak sense of 2017–remember all those blockchain companies trying (and failing) to “disrupt” the art market? No, 2019 has been one of actual, physical disruption, from the Hong Kong protests to the shock $3.7bn buy of Sotheby’s by the French-Israeli businessman Patrick Drahi, to Brexit wreaking havoc with the UK as it is kicked ever further down the road.

And then to top the year off, last week's unforgettable #bananadrama. Maurizio Cattelan's $120,000 banana duct-taped to the wall of Perrotin's stand at Art Basel in Miami Beach went viral causing such a frenzy that it was first eaten by the peckish "performance artist" David Datuna (he was escorted from the fair) and then its replacement, another banana, was removed from display on the final day of the fair due to “several uncontrollable crowd movements" which "compromised the safety of the art works around us, including that of our neighbours,” said the gallery.

As so often with the art market, you could not make it up.

But 2019 has been a year of fair drama across the globe with the cancellation of events worldwide, starting with Art Stage Singapore in January, followed by the announcement that the city’s new fair Art SG, scheduled to take place last month, has also been pushed back to 2020. In March, New York’s Armory Show was abruptly booted out of part of its venue days before it was about to open, when one of the Chelsea Piers was deemed structurally unsafe. The Armory pulled rank over its sister fair Volta, which forfeited its space in order to house a third of the Armory’s displaced exhibitors. Another Armory Week fair for younger galleries, Nada, had also been cancelled as its venue was suddenly redeveloped. And the Brussels edition of Independent was scrapped due to both venue and scheduling difficulties in the cramped fair calendar.

Meanwhile, the organiser of Art Berlin has announced today that the Modern and contemporary art fair, which has taken place in hangars belonging to the now-defunct Tempelhof airport for the past two years, will no longer take place. Koelnmesse, a company that organises around 80 trade exhibitions a year including Art Cologne, says the use of Tempelhof from 2020 is not secured and that the financial results of the previous editions were “not satisfactory.”

An evolutionary pressure is pushing everybody to the same end: grow or dieMarc Glimcher, Pace Gallery

It’s tough to be a smaller fish in the art industry, but David “Robin Hood” Zwirner swept in to the rescue of some of the displaced Volta galleries, offering up his 525 West 19th Street location by way of a replacement. This pocket of Manhattan’s Chelsea has embodied the expanding gulf between the haves and have nots of the gallery world this year, with competitive building between the mega galleries—most notably Pace, which opened its eight-storey monolith in September. But the space race within these few blocks continues apace—Gagosian, Hauser & Wirth and Marlborough are all expanding (all completing next year) and, not to be outdone, Zwirner is building a 50,000 sq. ft, Renzo Piano- designed tower in a formerly vacant plot. Expected to open in 2021, it is budgeted for “$50m-plus” according to a gallery spokeswoman. Pace’s president and chief executive, Marc Glimcher, cites an “evolutionary pressure” in the art world that is “pushing everybody in this business toward the same end: grow or die”. But where will this Darwinian survival of the fittest/richest end? And who are all these thousands of square feet for? “The artists,” the galleries will tell you, but, when it comes down to it, a bulging starchitect-designed gallery is a primal assertion of dominance.

Hauser & Wirth’s €4m art centre on Isla del Rey in Menorca, due to open in 2020, includes a programme of artists’ residencies Photo: Damian de Clercq, Courtesy Hauser & Wirth

Another city is on the up in 2019 too–Paris, helped by Brexit taking the lustre off London. Zwirner opened a gallery there during Fiac in October and White Cube will open an office soon. Rumours swirl that Hauser & Wirth is also looking for a premises, but a spokesman says "non": “There is no news regarding a potential Hauser & Wirth location in Paris.” Too obvious—instead, in June the ever capricious gallery announced it will open an art centre on Menorca’s Isla del Rey, off the coast of Spain, next year. Marc Payot, a partner and vice president of the gallery, says “such big decisions are really artist-driven. We go where they go and where they want to be”. It’s all about keeping hold of artists, and artists, it seems, want to be in the Balearics. Cue art world Love Island.

The “megas” were more in evidence than ever at this year’s (supposedly non-commercial) Venice Biennale, sponsoring shows of their artists and hosting lavish parties in their honour. As one observer puts it, ten years ago commercial galleries would have kept a low profile, but now they practically “have desks out front [of the pavilions] and are hosting the whole bloody thing”. The assiduous engineering of artists’ markets is increasingly palpable, not least in the support of museum shows. Take, for instance, the German artist Albert Oehlen, whose solo show at the Serpentine (until 2 February) is sponsored by Sotheby’s and three galleries, Gagosian, Skarstedt and Galerie Max Hetzler, all of which held exhibitions of Oehlen’s work–in Hong Kong, New York and London–to coincide with the show.

Our contributor Scott Reyburn identifies the Oehlen push as an attempt to mould new blue-chip names as supply is squeezed. “The whole market is treading water,” Reyburn says, reviewing last month’s “gigaweek” sales in New York on The Art Newspaper Podcast. This has been a relatively muted year for auctions, particularly in London where the air was sucked out by Brexit fears. But there has also been a lack of major estates, the lifeblood of auctions—thank heavens, then, for the divorce of Harry and Linda Macklowe, who have been told to liquidate their collection worth more than $700m. That will come through next year and the gloves are off for the consignment—expect some hefty guarantees.

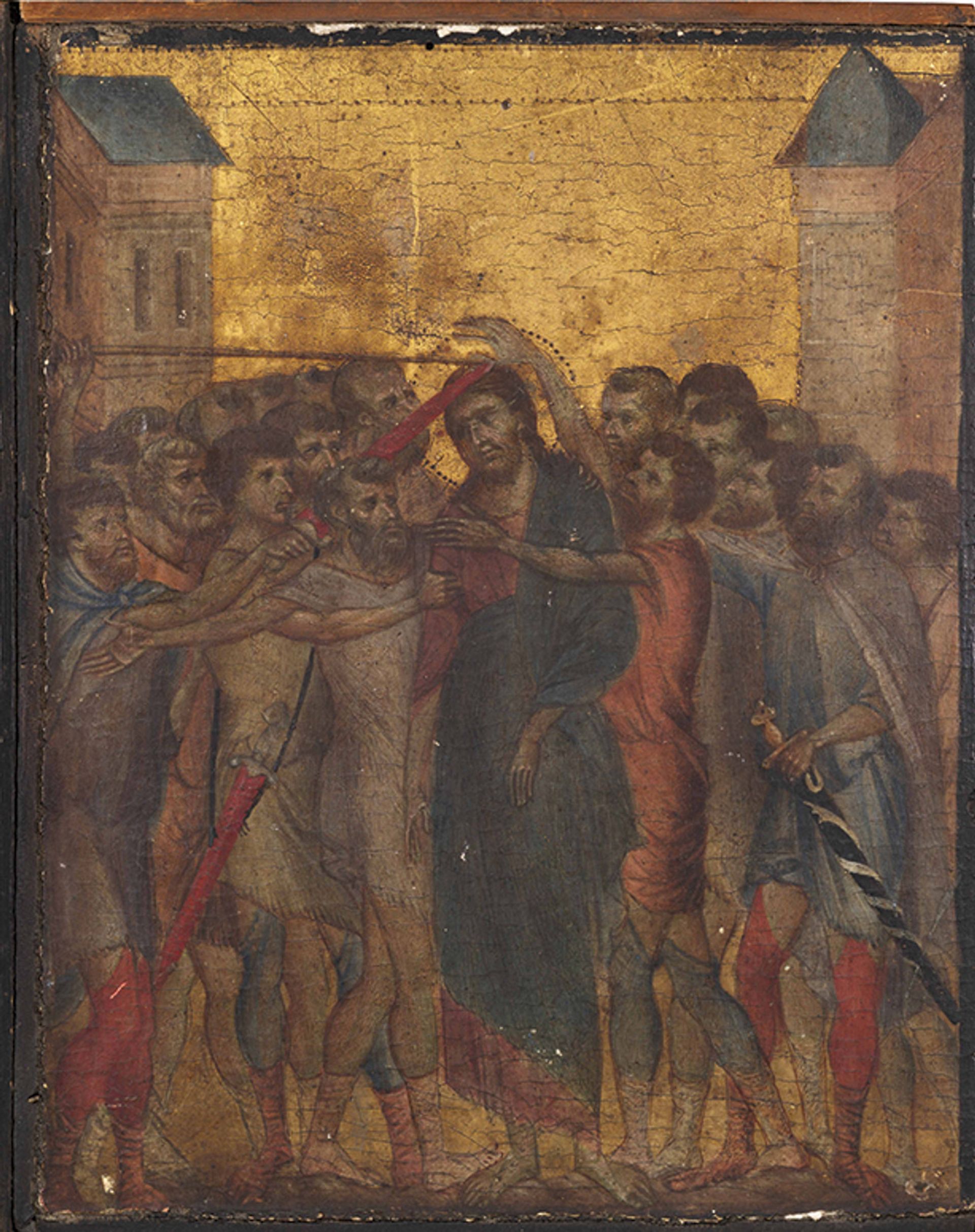

A good year for Old Masters discoveries: Cimabue's 13th-century Mocking of Christ

While confidence in the contemporary, Impressionist and Modern markets is down, according to ArtTactic, Old Masters continue on their own enigmatic path and this has been a good year for discoveries–the three notables all found in France and none sold by Christie’s and Sotheby’s. First, the so-called “lost Caravaggio”, the contentiously attributed Judith & Holofernes that was found in a Toulouse attic and scheduled to be auctioned in June with an estimate of €100m-€150m. But then it was sold privately, apparently to the US collector J. Tomilson Hill. Then came the sale of a little 13th-century painting of the Mocking of Christ, found in a kitchen and attributed to the Florentine artist Cimabue, for €24.1m (with fees) in the northern French city of Senlis. A fortnight later and a new record for another “new” work by the 17th-century (female) artist Artemisia Gentileschi, which had been in a private collection in Lyon for the past 40 years and sold for €4.8m (with fees) at Artcurial to a British buyer.

Consumers as opposed to collectors are, perhaps, the real disruptors now

It seems absurd to consider such old-school rediscoveries—and the accompanying scholarly backbiting—as part of the same amorphous art market as the craze for Banksy and Kaws. Yet we do, and 2019 has been a big year for the street artists taking the auction rooms by storm—and putting the taste police’s noses out of joint. First in March, The Kaws Album (2005) by the US artist Kaws (aka Brian Donnelly) sold for a staggering $14.7m at Sotheby’s in Hong Kong. Then in October, Sotheby’s sold Banksy’s chimp populated Devolved Parliament for £9.9m (a rare moment of sparky bidding in London). Both caused outrage, even disgust, among the establishment–the curator Francesco Bonami wrote a tirade in response to the Banksy sale in La Repubblica, signing off by dubbing Banksy and Kaws “the nothings that threaten everything”. And perhaps that’s the thing—theirs is a populist market being driven by (dirty word) consumers, those outside the industry club, with a little help from social media. This is the elusive new audience that the art market needs and claims to want, but it’s an audience that doesn’t know or much care about accepted conventions. Consumers as opposed to collectors are, perhaps, the real disruptors now.

Populist power: Kaws' NYT (Companion Close Up) was snapped up at Christie's © Guy Bell/Alamy Stock Photo