In the past decade, gun violence has reached crisis levels in the US, with an estimated 500 mass shootings in 2019, according to the Gun Violence Archive, an organisation that tracks data nationally on shootings in which four or more people were injured or killed. In Florida alone, there have been at least 11 such incidents this year. Communities and individuals impacted by gun violence are now having pressing conversations about the role public memorials play in honouring the victims and survivors of mass shootings. And in their designs, monument-makers must accomplish the difficult task of visualising the magnitude of such violence while respecting the individual lives lost.

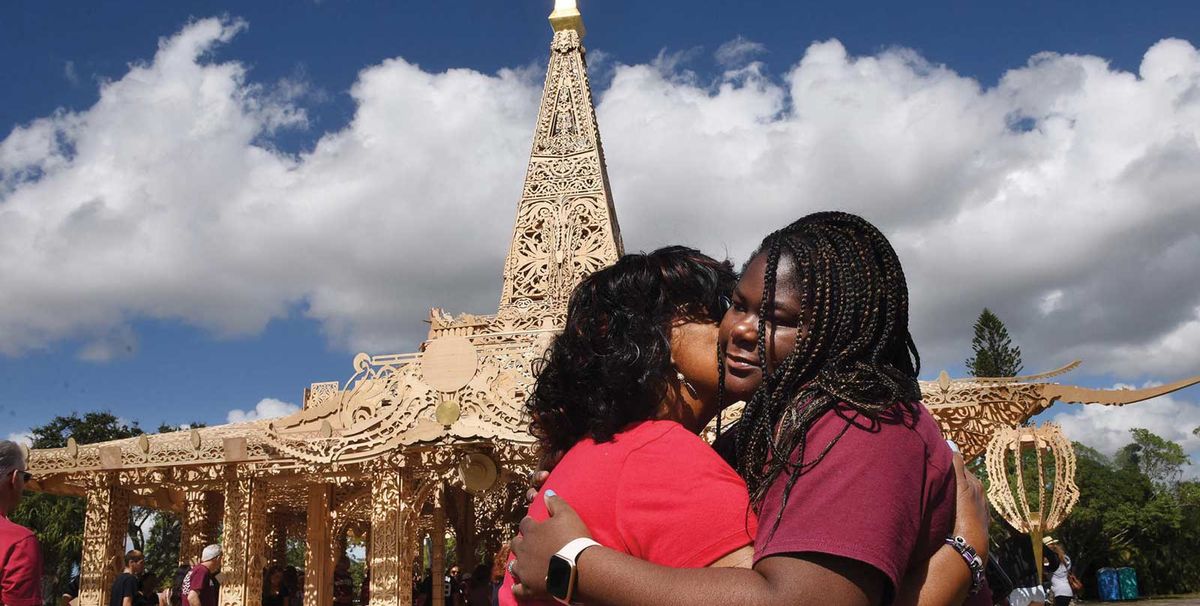

Less than an hour outside Miami, Coral Springs residents affected by the shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School observed the massacre’s one-year anniversary on 19 May by burning a monument to the ground. The temporary plywood structure, called Temple of Time, was designed by the artist David Best as a cathartic release for a community mourning the loss of 17 lives. The project received $1m from Bloomberg Philanthropies as part of its nationwide Public Art Challenge initiative to fund art works “that address important civic issues”.

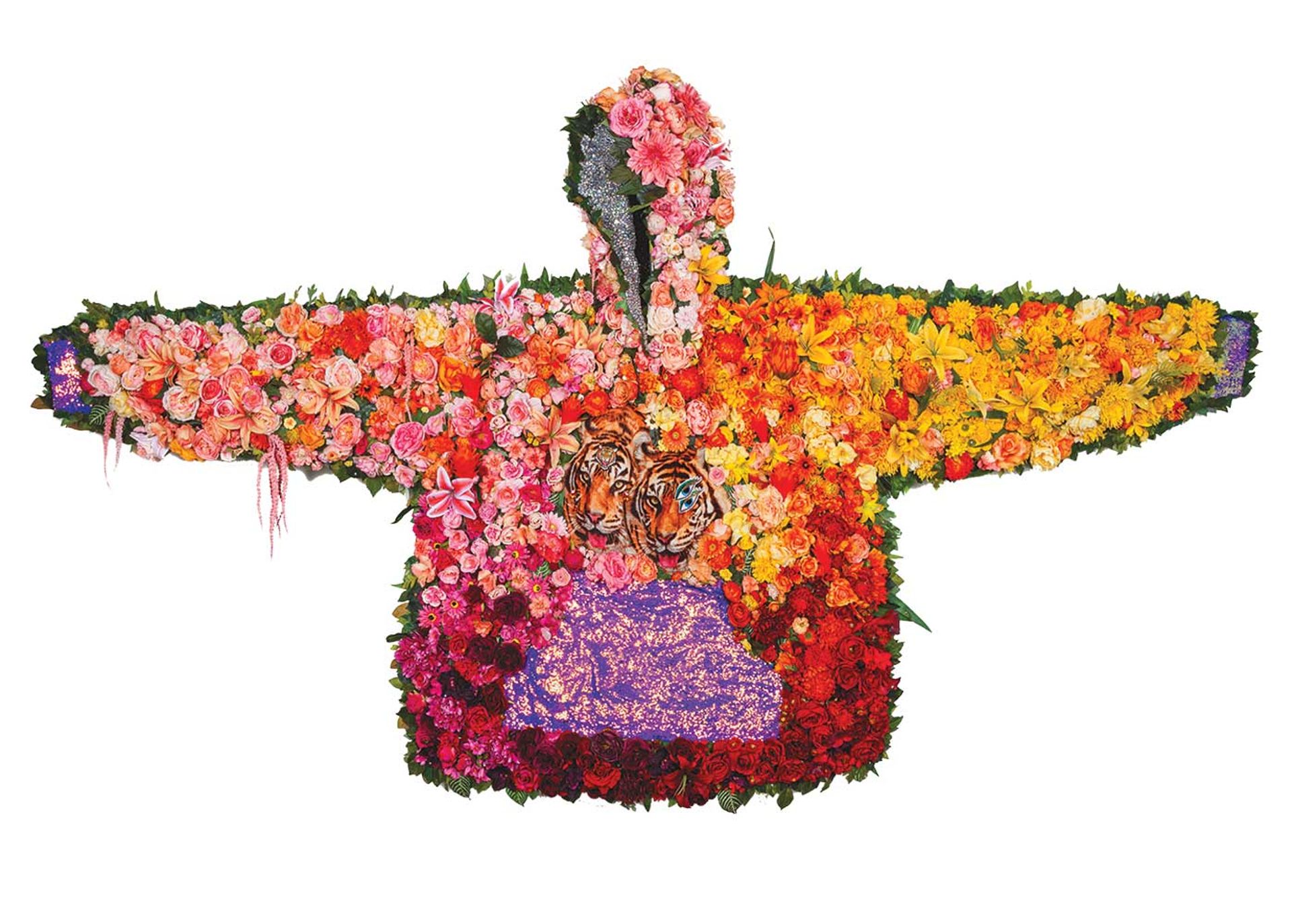

Gun violence is such a prevalent cultural motif in the US that it has become its own subgenre of art and can even be found at fairs. At Art Basel in Miami Beach, for example, the Chicago dealer Kavi Gupta is showing an untitled hoodie sculpture by the artist Devan Shimoyama that references young black shooting victims like Trayvon Martin, while at Design Miami, Philadelphia’s Wexler Gallery is presenting an installation of large funerary urns and teddy bears by the ceramicist Roberto Lugo that call to mind the makeshift memorials to victims found on community streets.

Devan Shimoyama’s Untitled (2019), referencing black shooting victims such as Trayvon Martin, whose killer was exonerated under Stand Your Ground © John Lusis

But large-scale memorial efforts such as a planned $45m cultural complex in Orlando near the site of the 2016 Pulse nightclub shooting, where 48 people were killed, have seen significant pushback from survivors, victims’ families and lawmakers. They have accused the organisers—the LGBTQ club’s former owner, Barbara Poma, and the OnePULSE Foundation she leads—of profiting from a national tragedy with a lurid tourist trap.

“A mass shooting is being used to generate money—none of which is going to the survivors,” says Zachary Blair, an organiser with the Community Coalition Against a Pulse Museum, noting the chasm between the museum’s multi-million-dollar budget, and the financial and physical hardships of Pulse victims. “Three survivors in our coalition have been in and out of the hospital while protesting the proposed museum. One has a colostomy bag, another has metal rods in his leg; and another still has to go to the hospital’s emergency room because the nerves [in his back] get so inflamed.”

Memorial to honour the 49 shooting victims of Pulse nightclub in Florida © Red Huber/Orlando Sentinel/TNS/Alamy Live News

The National Pulse Memorial and Museum concept design from Coldefy & Associés, which features a reflecting pool Courtesy Coldefy & Associés with RDAI/onePULSE Foundation

Instead of pouring millions into a high-profile museum, activists say, a memorial garden would be more appropriate. And because it would be cheaper, money left over could be directed towards a fund for survivors. Many other communities affected by gun violence have opted for healing green spaces—including El Paso, Thousand Oaks, Sandy Hook, San Bernardino and Las Vegas. “How can we put our loved ones to peace when we are constantly climbing over their bodies to build this damn tourist attraction?” asks Jessenia Marquez, whose cousin Brenda McCool was killed in the shooting, while her daughter Kassandra Marquez survived by hiding in a bathroom stall. Three years after the attack, Kassandra still cannot work full-time because of intense anxiety, and funds that support her therapy have run out. The closest free clinic, meanwhile, is more than an hour away. “What we need is greenery, not a gift shop. Something that will create peace and harmony,” Marquez says.

Advocates of the museum project say that its exhibitions and educational resources will have a positive impact on the city’s healing process. “The National Pulse Memorial and Museum will honour the 49 lives taken and all those affected, while also educating visitors and future generations on the profound impact the tragedy had on Orlando, the US and the world,” said Poma, OnePulse foundation’s chief executive, in a statement. The foundation also announced it would be awarding 49 annual scholarships, of up to $10,000 each, in honour of the victims, to “empower students who share similar dreams, ambitions and goals”. Applications opened on 1 December, with preference given to candidates “who are immediate family members of the 49 victims, as well as all the survivors of the tragedy”, according to a release.

But the intense public scrutiny over memorials to gun violence have left some arts professionals asking: What can these monuments offer to victims of an epidemic as widespread, ongoing and incomprehensible as gun violence? “There is a rush to memorialise,” says Harriet Senie, an art historian who has written extensively on the topic. “We now have a situation where people aren’t taking their time; they are distorting history and making questionable aesthetic decisions. Permanent memorials need more time to develop. We can’t expect people to take the long view when they’re in mourning.”

There is a rush to memorialise. We now have a situation where people aren’t taking their time; they are distorting history and making questionable aesthetic decisions.Harriet Senie, art historian

“Today, memorials are seen as an expression of our cultural values,” says Michael Murphy, the executive director of MASS Design Group (MSG), an architecture firm that has come to specialise in the monuments field with critically recognised projects such as the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Alabama and the Kigali Genocide Memorial in Rwanda. “We must ask how these monuments might affect systemic change,” he adds. “And there does seem some need for contemporary memorials to allow the public to engage.”

Participation and collaboration are two key elements of the design group’s Gun Violence Memorial Project at this year’s Chicago Architecture Biennial, which closes in January. Comprised of four glass houses made of 700 hollow white bricks, the installation—a collaboration between MASS, the artist Hank Willis Thomas, and the advocacy groups Purpose Over Pain and Everytown for Gun Safety—includes audio from victims’ families and mementos from loved ones.

MASS also submitted a proposal to design the National Pulse Memorial in Orlando, partnering with artists including Sanford Biggers and Richard Blanco on a proposal that aimed to “put the Pulse massacre in a global context of the fight for equality”. A competing design by the architectural firms Coldefy & Associés, with RDAI and the Orlando-based HHCP Architects, the French artist Xavier Veilhan, and other partners, was ultimately chosen for the project. “Together, we have an opportunity to reclaim a place from terror and darkness and create a new reality, one that brings people together in celebration of joy and love,” Thomas Coldefy said in a statement.

Many survivors and victims’ families still feel steamrolled by the OnePULSE Foundation’s plans for the complex. “This was originally supposed to be a museum about gun violence, but in order to access state money, OnePULSE decided it should be about gay inclusion and diversity,” explains Zachary Blair from the Community Coalition Against a Pulse Museum.

Florida has few restrictions on gun ownership and a controversial 2005 law known as “Stand Your Ground”, which allows residents to use deadly force to defend themselves or others and provides them immunity from criminal prosecution or civil action for doing so. “They are pivoting because of Florida’s conservative politics,” says Blair.