Twenty-five years after the Rwandan genocide, in which one million people were murdered by Hutu extremists, mostly members of the Tutsi tribe but also moderate Hutus, Alfredo Jaar’s project about the 100-day massacre goes on show in the UK for the first time today.

The Chilean artist, who fled Pinochet’s regime for New York in 1982, recalls how, in August 1994, he became so incensed by the “barbaric indifference” of the world’s media to the mounting death toll, he decided to travel to Rwanda.

“I remember feeling the rage taking over my body and I thought, I have to go,” Jaar recounts. “Of course, everyone around me thought I was totally insane. They said to me: ‘You’re not going Alfredo’.”

But the artist remained firm. Having signed a release form issued by the UN, who said they could not protect him if something happened, Jaar and his assistant set off. “It was the craziest thing I have ever done, but it changed my life,” he says. “I always felt that, in my work, there is a before Rwanda and an after Rwanda.”

When you have a tragedy of a million deaths, it’s meaningless, it’s too abstract. So it’s important to reduce the enormity of the tragedy to one story, to one name.

Jaar spent three weeks in the violence ravaged country, meeting people in refugee camps and listening to their stories, as well as travelling to neighbouring Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of Congo), Uganda and Burundi where millions of Rwandans had fled.

“I took more than 3,000 pictures, the most horrible images I have ever seen and taken in my life,” he says. But he has never shown them, nor will he (some he has hidden in ash-grey linen boxes, creating memorial sculptures out of the blocks). “That was the ethical position I took as an artist,” he explains. “I’m not going to show this, I’m not going participate in this pornography of violence. I’m going to do something else.”

That something else is what Jaar has described as his “most difficult project”, a series of 21 pieces created over six years, between 1994 and 2000. Six of the works are now on show at London’s Goodman Gallery, as well as one new neon work, And Yet (2019), based on a poem by the Russian poet Anna Akhmatova. It is, Jaar says, his response to the recurring violence of contemporary politics.

The earliest piece on show, Untitled (Newsweek) (1994), comprises 17 covers of the US magazine installed in a row on light boxes. The first is dated 11 April 1994. As Jaar’s caption points out, this was five days after a plane carrying the presidents of Rwanda and Burundi, both Tutsis, was shot down above Kigali. Their deaths sparked widespread massacres. But Newsweek’s cover shows a bear tearing through a sheet of financial stocks and shares, with the strap line: “how to survive in a scary market”.

It was not until 1 August—17 weeks later—that the magazine dedicated its first cover to Rwanda, at which point the monstrous death toll had reached one million people. “Hell on earth: Racing against death in Rwanda” read the headline, which Jaar says was inaccurate. “There was no race, it was too late,” he says.

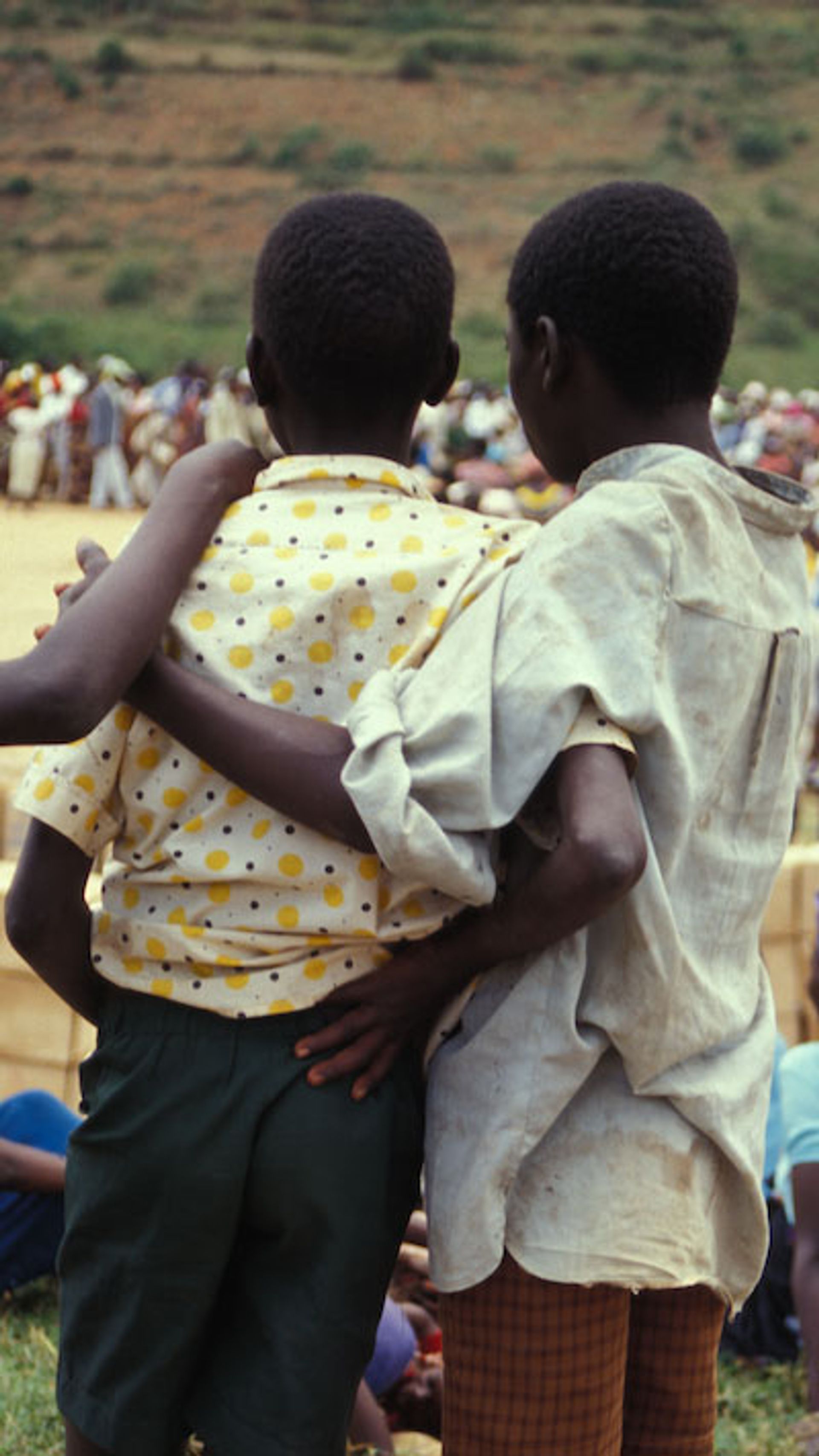

Alfredo Jaar, Embrace (1995)

Children feature in several of Jaar’s photographic works, although he never reveals their faces, choosing instead to use cropped or blurred images. Six Seconds (2000), an out of focus shot of a girl with her back to the camera, is the final work in the project.

Jaar encountered the girl in 1994 in the Nyagazambu refugee camp, but, after just six seconds, she turned and left. Jaar’s camera was hanging from his neck so he hurriedly photographed her back, resulting in the blurry image. For six years, Jaar held onto the picture, convinced he could not use it, but later realised that the fuzzy quality exactly expressed his “incapacity to represent a certain reality—everything is always out of focus”.

The centrepiece of the exhibition is The Silence of Nduwayezu (1997), a pile of one million slides heaped on a light table, all featuring a close-up of the eyes of one boy: Nduwayezu, a five-year old Tutsi whom Jaar met at a refugee camp in Rubavu. Nduwayezu, like many children, had witnessed the brutal murder of his parents, and had been so traumatised he had not spoken for four weeks.

Alfredo Jaar, The Silence of Nduwayezu (1997)

The aim of the piece, Jaar says, is to humanise the genocide, to bring Nduwayezu’s story into focus; viewers are encouraged to scrutinise the images through magnifying glasses on the table. “When you have a tragedy of a million deaths, it’s meaningless, it’s too abstract,” Jaar says. “So it’s important to reduce the enormity of the tragedy to one story, to one name.”

He adds: “This way people can identify with that person, and feel solidarity or empathy. Once you know the story, you cannot dismiss this image.”

It would seem people have indeed felt a sense of solidarity. Over the past 22 years, more than 150,000 slides have been pocketed from the installation; something Jaar does not actively encourage, but turns a blind eye to.

“We have an insurance system where at the end of the show, we count the slides and put them in their boxes and if there are some missing the insurance pays us and we replace them,” he says. “I don’t see it as stealing. Maybe people feel guilty or maybe they feel empathy, but it seems people want to keep the eyes close to them. And now they are in people’s homes all around the world.”

I don’t think that we should condemn to invisibility these realities because we do not belong to these realities.

Questions of representation, particularly of black bodies, have become increasingly pertinent in recent years. So what place does Jaar’s project have in relation to that particular discourse?

“I think it’s my duty and my privilege and my responsibility as an artist to try to bring some light to these realities that are being ignored by the media,” he says. “I don’t think that we should condemn to invisibility these realities because we do not belong to these realities.”

There are ways, Jaar says, to “talk about violence without exercising violence again on the victim, you can talk about racism without actually committing an act of racism”.

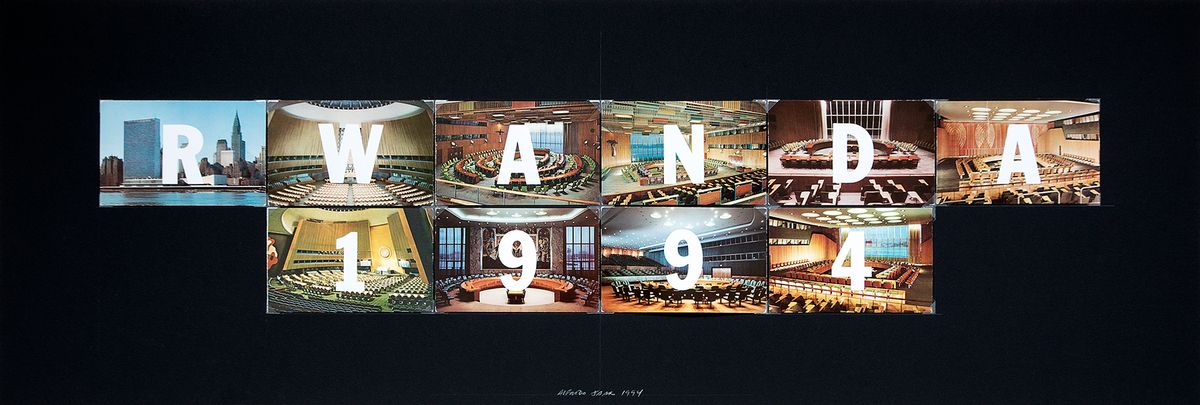

Twenty-five years on and Rwanda is still grappling with the legacy of the genocide. World leaders have expressed regret over failing to stop the massacre, but it is too late, Jaar says. One of his works refers to the decision by members of the UN’s Security Council to not intervene despite having knowledge of the atrocity before it happened.

There were plans for Jaar to create a memorial in Rwanda, but a lack of funds has put the project on hold indefinitely. “I hope one day it happens,” Jaar says. For now, his project exposes the West’s failure to respond 25 years ago—and the racism that still persists.