Two of Paul Gauguin’s Tahitian paintings were buried in the grave of a young boy in 1892. Although this little-known fact is mentioned briefly in the National Gallery’s exhibition Gauguin Portraits, which opened in London last month, we can report the precise source of this astonishing story.

In 1891, a few days after his arrival in Tahiti, Gauguin found lodgings in the capital, Papeete. His neighbours, with whom he shared a veranda, were Jean-Jacques Suhas, a French naval pharmacist, and his wife Mareta Helena Teura Nivanui Burns, who had British and royal Tahitian blood. They had married four years earlier and had a one-year-old son, Aristide (affectionately known as Atiti) .

Gauguin was there when the infant later took his first steps on their veranda. The artist loved playing with Atiti and painted two pictures to adorn his nursery. Although Gauguin was regarded as selfish among his peers, the artist’s concern for the young child reveals a caring side to his personality. Decades later, the Suhas family recalled that Atiti “marvelled” at his paintings—although few other Tahitian residents did.

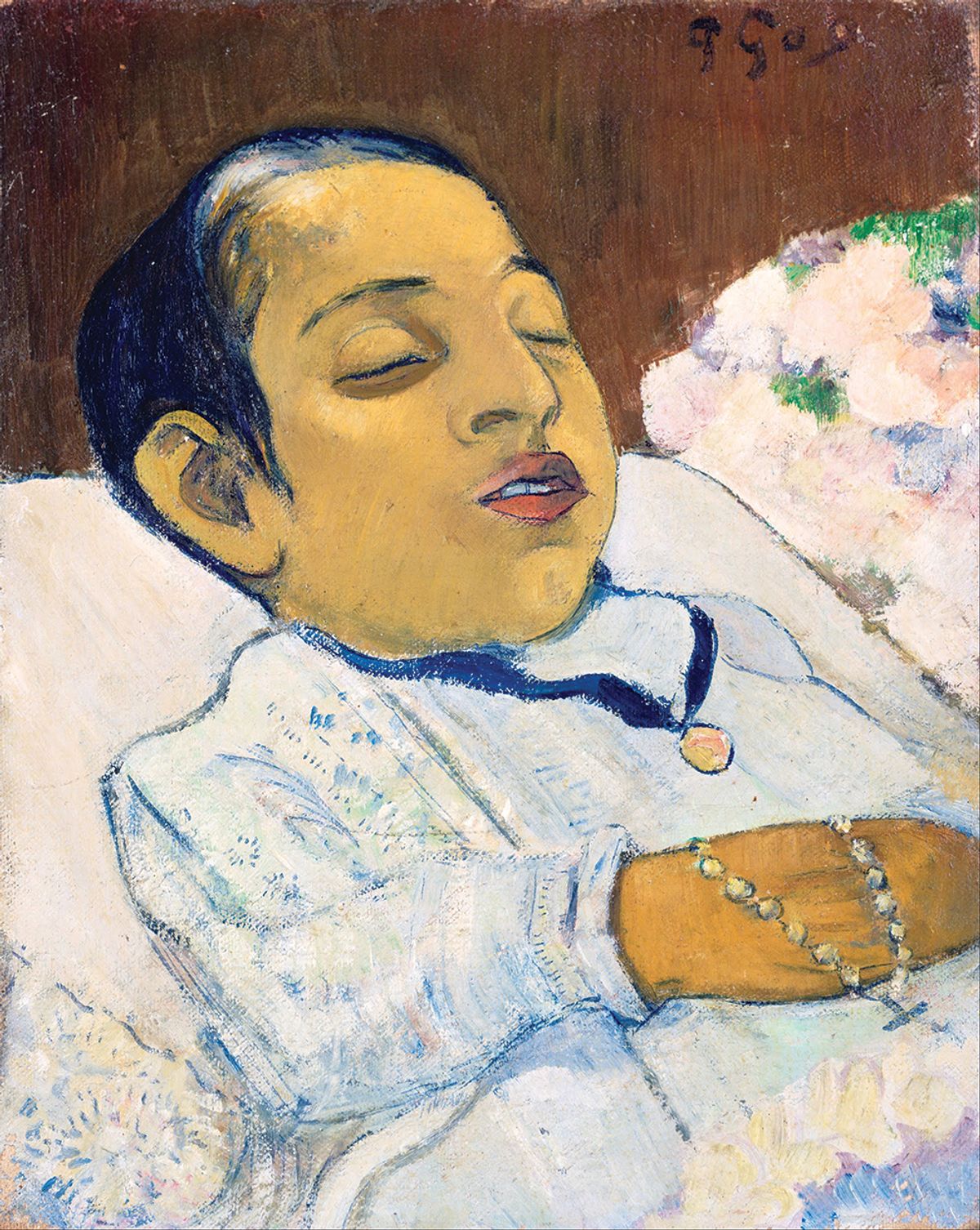

Tragically, Atiti later developed a stomach illness and died on 5 March 1892, when Gauguin was staying in Papeete. According to local Catholic custom, the body of the young boy was laid out, with his eyes closed and formally dressed. A rosary was draped over his right hand and he was surrounded by tropical flowers.

It was common in Polynesian culture to bury relatives with objects highly valued by the family

Standing beside the tiny body, Gauguin painted a deathbed portrait for the grieving parents. Atiti’s mother kept it as a treasured object in a special wooden box, later taking it to France when the family moved to Aix-en-Provence in the early 1900s. The painting was eventually inherited by Atiti’s sister, Florida Suhas, and sold to the Kröller-Müller Museum in the Netherlands in 1951.

The two pictures that Gauguin painted for Atiti’s nursery were interred with his body. This was reported in a long-forgotten article by the writer and art collector Louis Giniès in the Marseille-Matin newspaper of 21 December 1937 (copy in the Kröller-Müller files), following an interview with an unnamed child of Florida Suhas. Giniès wrote that “the two canvases of Gauguin which had decorated the room of the infant were buried with him”.

Elizabeth Childs, an American Gauguin specialist who contributed to the National Gallery catalogue, has seen the Giniès account and accepts it as very plausible: “It was common in Polynesian culture, even into modern times, to sometimes bury relatives with objects which were highly valued by the family.”

But the two Gauguin canvases will not have survived—like the body of the young Atiti, little will now remain of them after having been buried for well over a century.