Around ten years ago, Martin Parr bought a small flat by the beach in Tenby, the seaside resort in Pembrokeshire, South Wales. This, he says, is where he plans to retire once one of the most important documentary photography careers in the history of the medium finally draws to a close.

“I’ve visited and photographed all the seaside resorts in the UK over the years,” Parr says when we meet at his new exhibition, Martin Parr in Wales (until 4 May 2020), at Wales’s National Museum in Cardiff. “Tenby is the best. It’s like a postcard. But, unless you’re in Wales, you don’t know about Tenby. All the British middle classes go to Padstow. But Tenby’s a secret, so keep it quiet.”

In preparation for his retirement, Parr has started to use a telephoto lens—like Jimmy Stewart in Rear Window—to capture Tenby’s beach-goers at a distance. “I sit in my living room, with my long-distance camera, preparing for old age,” he says. He pictures the snaking queues for the ice cream van, the accidental patterns of deck-chair loungers, the old ladies with their fish and chips and ’99 Flakes and circling sea gulls, the children shivering in the sea. “They’re a precursor of things to come,” he says.

Parr loves Wales, and has lived just over the border, in Bristol, for more than 30 years. Since the mid-1970s, Parr has travelled to and photographed the country’s unique national character, from the bingo afternoons and disco nights at Llanharry Working Men’s Clubs, to the sonorous gaping mouths of Llantrisant Male Voice Choir, to the cakes of Merthyr Tydfil’s tea-rooms and the pies of Abergavenny. Most movingly, he photographed from within Wales’ last deep pit coal mine at Tower Colliery, capturing the last vestiges of Wales’ proud coal mining heritage; the men cleaning the soot off each other in the showers, or drinking tea, caked in dirt, between shifts.

Martin Parr, Tower Colliery, Glamorgan, Wales (1993) © Martin Parr/Magnum Photos/Rocket Gallery

Parr’s evocation of Wales is one of three major exhibitions to open at the same venue in Cardiff last month. Fittingly hung alongside Parr’s work is Bernd and Hilla Becher’s Industrial Visions (until 1 March 2020); a topographical study of Welsh industry.

This exhibition has been a long-time in the making. The show's co-curator Russell Roberts was working with Hilla Becher in the months prior to her sudden death in 2015. The exhibition has now been finally realised with the help of the Becher’s son, Max.

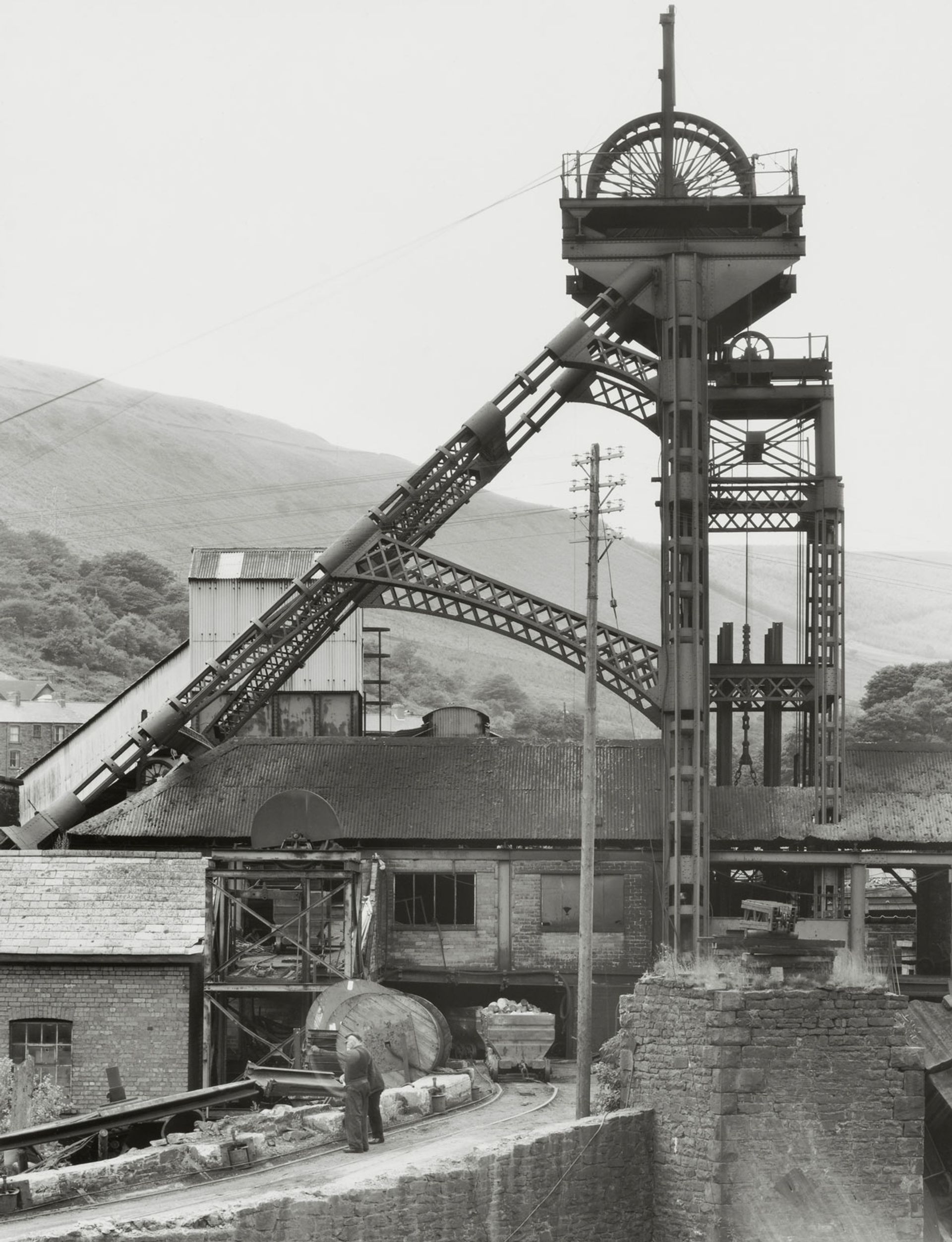

The married German couple, whom spent their 50 years together documenting industrial structures across Europe and America, viewed Wales’ winding towers, blast furnaces, cooling towers, gasometers, grain elevators, water towers and lime kilns as something akin to religious architecture. In the book What Beauty Is I Know Not, a catalogue for the 1971 Nuremberg Biennale, which is referred to in the exhibition, they note: “Just as cathedrals came out of the medieval world view and castles embody the feudal system, these edifices are to be seen as emanations of our time, a self-representation of our society.”

Bernd and Hilla Becher's Deep Dyffryn Colliery, Mountain Ash, South Wales, GB (1966) © Estate Bernd & Hilla Becher, represented by Max Becher, courtesy Die Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur – Bernd und Hilla Becher Archive, Cologne, 2019

The Bechers first visited Wales in 1965. Fascinated with the structures that under-girded the economy and culture of The Valleys, they applied for funding from the British Council, returned the following year in 1966 and based themselves in a campsite in Glynneath. For three months they drove from one town to the next, carefully recording each and every industrial structure in South Wales via exacting and meticulous large-format photographs. In all, 225 images were created, and are on show in Cardiff today.

The Bechers spoke of their want to create “the perfect chain” - each photograph was produced in exactly the same way, from one of three pre-planned perspectives. The structure would take up the whole frame of the picture, and be taken in shadowless conditions before being carefully proceeded as a silver gelatin print.

Despite their uniformity and neutrality, the images possess a power “that won’t be easy” for many of the exhibition’s visitors, predicts co-curator Dr Russell Roberts. The images, he says, “carry with them a sense of lament or melancholy. It is a landscape that has now, in many cases, been erased and repurposed. They are monuments to a lost world of labour.”

August Sander, August Sander, Pastrycook, Konditor (1928) © Die Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur - August Sander Archiv, Cologne / DACS 2019 Photo © National Galleries of Scotland

Finally, The National Museum Cardiff shows over eighty portraits by the German photographer August Sander’s monumental project People of the Twentieth Century (26 October - 1 March 2020), the German artist’s lifelong effort to catalogue ethnic and class diversity of German society in the decades after the First World War, under the democratic experiment of the Weimer Republic, and in the years before the rise of Nazism which led to World War Two. The German historian Golo Mann described the work as: “The twilight era between war and war.”

Sander once said of the series: "I hate nothing more than sugary photographs with tricks, poses and effects. So allow me to be honest and tell the truth about our age and its people."

In 1936, the Nazi government, which had recently come to power, destroyed the printing blocks for ‘People of the 20th Century’ and impounded unsold copies of the book. Sander’s representation of a heterogeneous German society was seen as degenerate. For that alone, it should be celebrated today.

The Sander exhibition is part of Artist Rooms, established in 2008 by the d’Offay Donation and jointly owned by National Galleries Scotland and Tate.