It is 17 years since the last Vincent van Gogh exhibition in Germany, but last week two quite different shows opened in Frankfurt and Potsdam. On the Wednesday it was Making Van Gogh: A German Love Story at the Städel Museum in Frankfurt. Just three days later Van Gogh: Still Lifes opened at the Museum Barberini in Potsdam, just west of Berlin.

Curators at the two venues insisted that they had each been working on their own shows for five years, so it is most bizarre that both arrived in the very same week. What went on behind the scenes remains cloudy, but there must have been delicate discussions between the two museums about their dates—and which would get in first.

Although keen international visitors could travel to Germany to view both exhibitions, the two cities are over 400km apart, which hardly makes that easy. There must have been competition to obtain loans that would have been relevant to both exhibitions (that is, still lifes that had been or still are in German collections). Critics are likely to review both shows together, reducing the coverage that the museums will get had the exhibitions not coincided.

And there is a risk that some members of the public will be confused, although the exhibitions are very different: Frankfurt examines Germany’s love affair with Van Gogh, while Potsdam focuses on the genre of still lifes. Both are very good shows, although in terms of size Frankfurt’s is by far the larger. Last week I discussed the Frankfurt exhibition on Van Gogh and Germany—so this week I am turning to the still life show in Potsdam.

Museum Barberini, Potsdam Photo: Martin Bailey

Van Gogh: Still Lifes is presented in the Museum Barberini, Frederick the Great’s 1770s palace. This was virtually destroyed by bombing during the Second World War and the software billionaire Hasso Plattner funded the recent complete rebuilding of the palace, which opened in 2017. The facade was totally reconstructed and the lost interior rebuilt as a museum. The Barberini (modelled after a Baroque palace in Rome) is now a major attraction in the heart of Potsdam’s historic centre.

Surprisingly, the Barberini’s exhibition is the first ever to focus on Van Gogh’s still lifes. Curated by Michael Philipp, it shows 27 paintings, presented simply and elegantly in a chronological display, divided into rooms covering the different places where the artist worked. The show ranges from the dark paintings of his Dutch period (1881-86) to the exuberantly coloured pictures of his final French years (1886-90).

So the exhibition starts rather quietly, with works painted in muddy brown tones, but quickly reaches his Paris stay—with a group of exciting flower still lifes. These include Vase with Poppies (1886) from the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art in Hartford, Connecticut. Long dismissed as a fake, earlier this year it was reattributed to the artist by specialists from the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam. They examined the canvas, ground layer and pigments, as well as undertaking stylistic and provenance research. The loan to Potsdam provides a very unusual opportunity to see the picture outside the Wadsworth Atheneum, since it has not been lent to an exhibition since 1913 (when it went to New York’s famed Armory show).

Vincent van Gogh’s Vase with Zinnias (1886) Private collection. Photo: Martin Bailey

Another important flower still life in Potsdam is the privately owned Vase with Zinnias (1886), which was shown with the Goulandris collection in Greece in 1999. (After that, the only time it has been seen was at the Van Gogh Museum, in its Sunflowers exhibition last summer.) Another magnificent loan to Potsdam is Grapes, Lemons, Pears and Apples (1887) from the Art Institute of Chicago, with its dizzying perspective.

Vincent van Gogh’s Grapes, Lemons, Pears and Apples (1887) Courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago, gift of Kate L. Brewster. Photo: bpk/The Art Institute of Chicago/Art Resource, NY

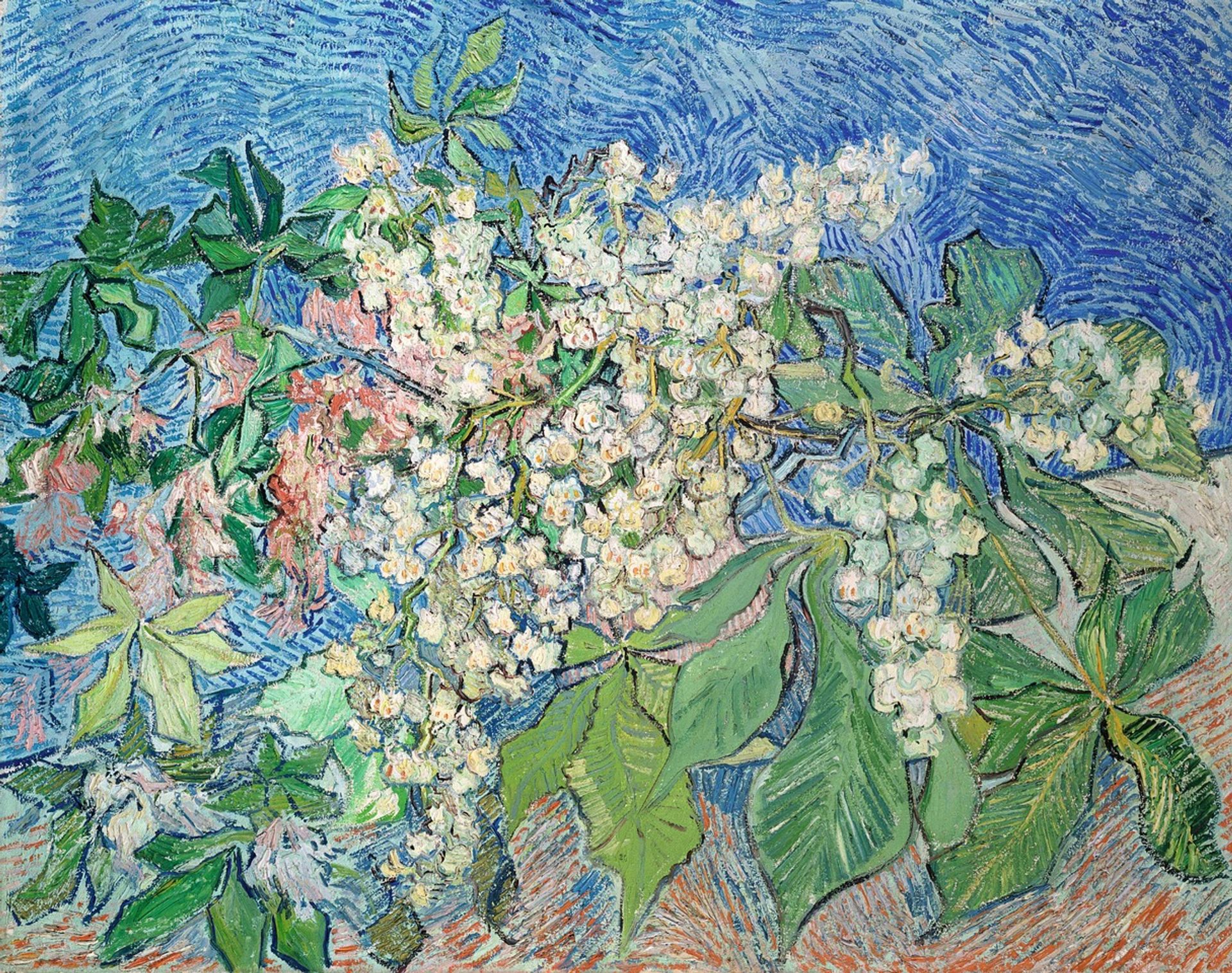

The Potsdam exhibition finishes with a single painting from Auvers-sur-Oise, hung at the end of the last room, almost like an altarpiece in a chapel. Blossoming Chestnut Branches (1890) positively explodes with colour and vibrant brushstrokes—the whitish-pink blossoms set against a swirling blue background. It is difficult to imagine that this optimistic work was completed just a few weeks before the artist’s suicide. Seeing a substantial sequence of Van Gogh’s still lifes hung together, for the first time, once again emphasises the enormous strides that the artist made during his tragically short career.

Vincent van Gogh’s Blossoming Chestnut Branches (1890) Courtesy of Sammlung Emil Bührle, Zürich. Photo: © SIK-ISEA, Zürich (J.-P. Kuhn)

Van Gogh: Still Lives, Museum Barberini, Potsdam, until 2 February 2020. The catalogue, which is available in English, includes a fully illustrated record of all 127 of Van Gogh’s still lifes.