The exhibition on Vincent van Gogh and Germany, which opened on Wednesday in Frankfurt, is one of the finest shows on the artist in recent years (other than those at the Amsterdam museum dedicated to the painter). The Städel Museum’s Making Van Gogh: A German Love Story focuses on Germany’s early infatuation with the Dutch artist.

Although Van Gogh was almost unknown outside avant-garde circles on his death in 1890, by 1914 he was—astonishingly—“by far the most popular modern artist in Germany”, according to the exhibition’s co-curator Felix Krämer. (In Britain, he remained barely known until the 1910 Post-Impressionist exhibition at London's Grafton Galleries, when he was widely ridiculed.)

The Städel exhibition is centred around 50 Van Goghs, which were either acquired by German collections or exhibited in Germany before the First World War. These are accompanied by 70 works by later German artists, painted up until the 1920s under the influence of the Dutch master—graphically illustrating his impact on early 20th century art in Germany.

The presentation is elegant, with a strong story line—although the exhibition title does come as rather a surprise. The main title is Making Van Gogh, using the English word, which is curious for an exhibition focussing on Germany. “Making” here refers not so much to the artistic process, but more to the creation of the Van Gogh legend and the deep appreciation of his work by German collectors and painters.

Just over half the show comprises paintings by early 20th century German artists—mostly of the Die Brücke group and the Expressionists—who were inspired by the Dutchman. This strong display includes works by Max Beckmann, Ernst Kirchner, Alexej von Jawlensky and Paula Modersohn-Becker.

Vincent van Gogh’s Farmhouse in Nuenen (1885), bought by the Städel Museum, Frankfurt in 1908 © Städel Museum-U. Edelmann

The show’s subtitle is “Geschichte einer deutschen Liebe” (A German Love Story). Considering the impact of Nazism on German collectors, most of whom were Jewish, along with the confiscation of “degenerate” Van Gogh paintings from German museums, the “love affair” could hardly have had a more apocalyptic ending.

The figures speak for themselves. By 1914 there were 150 Van Gogh paintings and drawings in Germany, two thirds of which were owned by Jewish collectors. Germany’s interwar financial problems and, much more seriously, the intense persecution of the Jewish community between 1933-45 meant that all the privately owned Van Goghs left the country: in 1945 there was not a single work left in a German private collection. Even today, there are no German collectors who own any paintings from the artist’s French period, when he produced his finest pictures.

The Städel is a most appropriate venue for Making Van Gogh, since it was the first German public museum to acquire his works. In 1908 it bought the painting Farmhouse in Nuenen and the drawing Peasant Woman planting Potatoes (both 1885), paving the way for museums in Berlin, Munich and other cities.

Following extensive research (and intensive loan negotiations), the Städel exhibition is able to provide a strong display emphasising the scope of Germany’s pre-1914 Van Gogh holdings. These are mainly presented in the first section of the show, giving an excellent overview of the development of Van Gogh’s work.

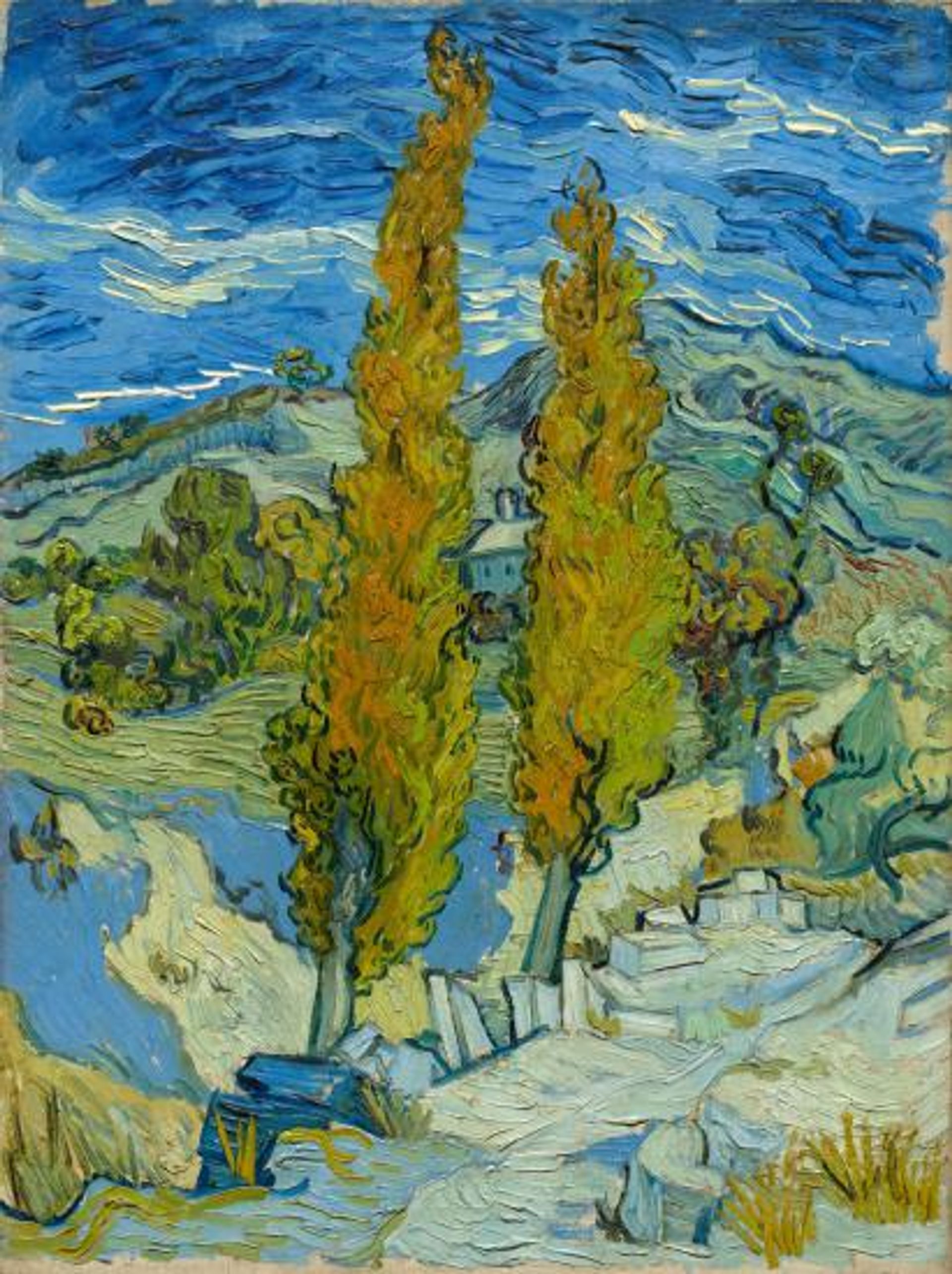

Vincent van Gogh’s The Poplars at Saint-Rémy (1889), bought by the Barmen collector Max Silber in 1912 Courtesy the Cleveland Museum of Art

Highlights include three 1889 paintings: View of Arles (Neue Pinakothek, Munich), The Ravine (Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo) and The Poplars at Saint-Rémy (Cleveland Museum of Art).

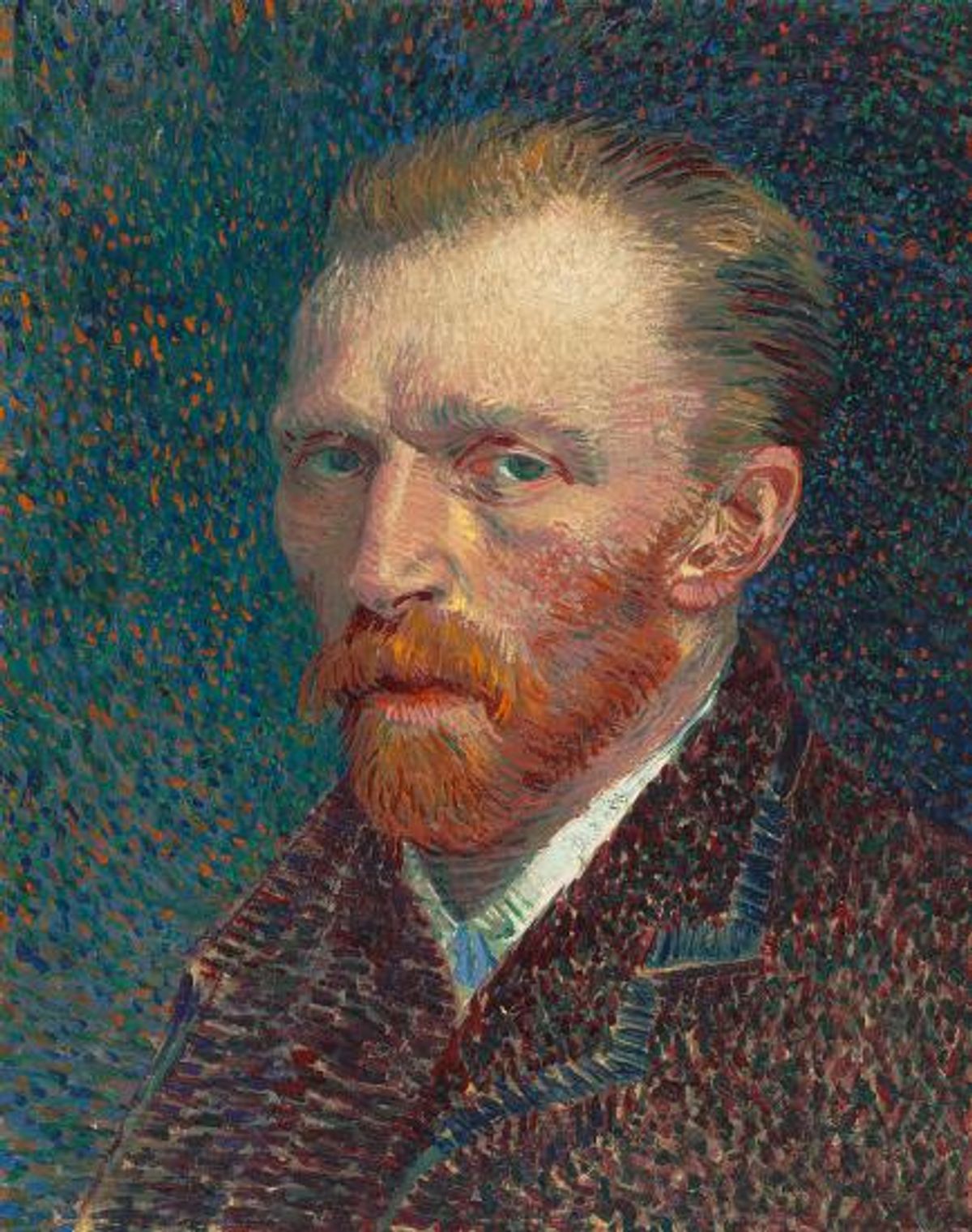

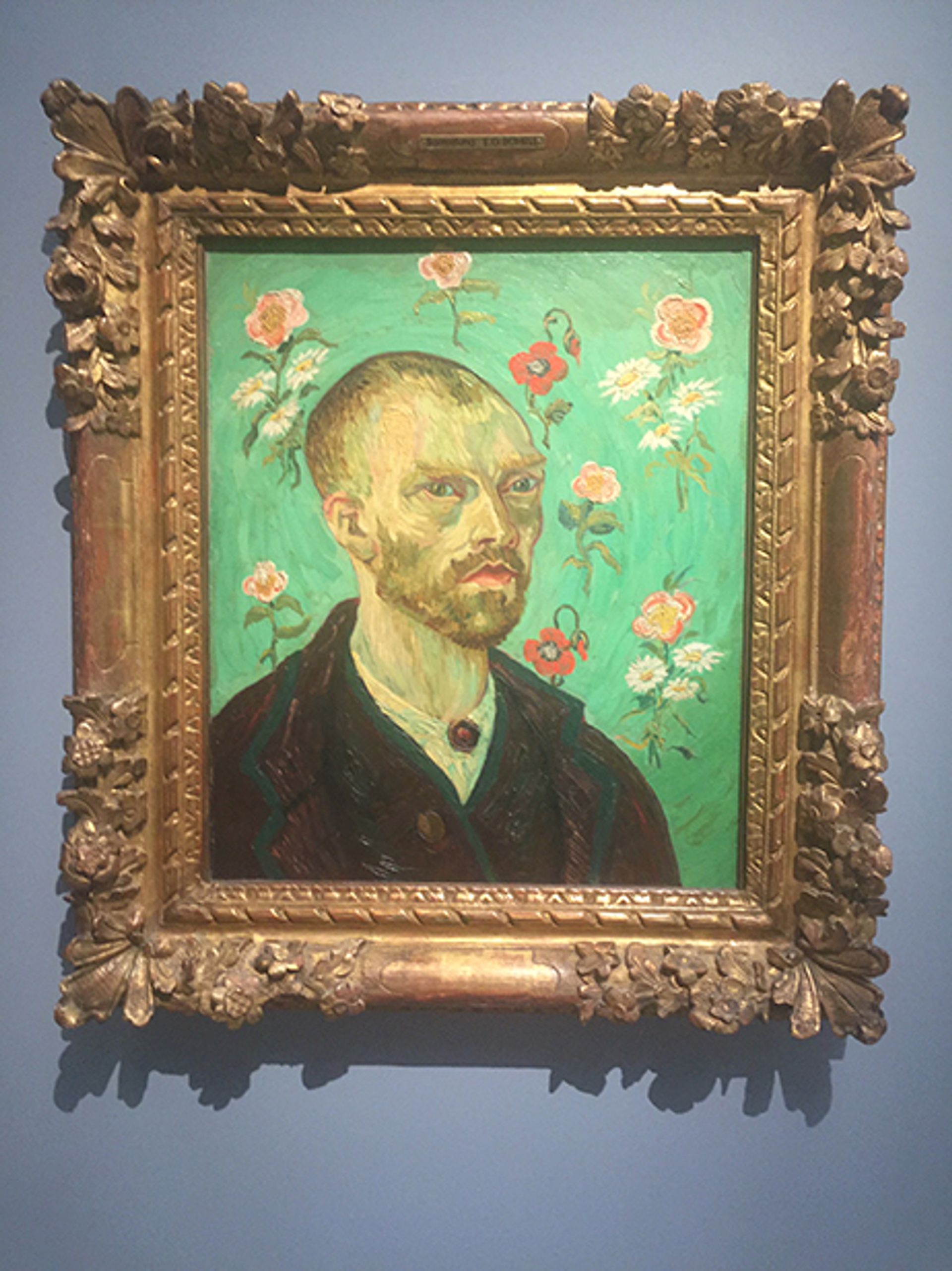

Van Gogh was so popular in Germany that this is where the first fakes appeared on the market. Among the surprises in the Städel show is an apparent self-portrait which is similar to the one which Van Gogh painted for Paul Gauguin (the original is now at the Fogg Art Museum, Cambridge, Massachusetts), but with an added background of flowers. Although this second “self-portrait” was painted as a homage by an admiring artist, Judith Gérard, it was subsequently reworked, with the added flowers, probably by Emile Schuffenecker and then marketed (without Gérard’s knowledge) as an authentic second version of the self-portrait. The Städel is now displaying it as a “fake”.

Judith Gérard and others, copy after Van Gogh’s Self-portrait for Gauguin (1897 and later) © Emil Bührle Collection, Zurich. Photograph by Martin Bailey

The tragedy is that Germany’s love story was brought to an abrupt end by Hitler’s hatred of the Jews (and his dislike of modern art). The Städel catalogue cites the only known comment made by Hitler about Van Gogh. I had found this quote for them in an unlikely English source, the memoirs of his former friend Ernst Hanfstaengl. In 1925, early in his political career, the Führer saw a reproduction of the Sunflowers and complained to Hanfstaengl that “the colours are too loud”.

Alexander Eiling, the exhibition’s other co-curator, comments on their show’s subtitle, saying that “with all love affairs, it starts with enthusiasm, but sometimes it cools”. Despite the utter disaster of the 1930s, Germany played a key role in developing a love for the artist whom we admire today—a story so well told on the walls of the Städel.

Making Van Gogh: A German Love Story, Städel Museum, Frankfurt, until 16 February 2020