Decades ahead of her time, the French artist and society figure Anne Marguérite Joséphine Henriette Rouillé de Marigny, Baroness Hyde de Neuville (1771-1849) grabbed life by the horns, enthusiastically sketching landscapes and people as an exile and outsider in a young America. An exhibition opening this Friday at the New-York Historical Society will track her adventures, presenting a visual memoir in the first thorough examination of this intrepid observer’s seemingly charmed life.

Through the display of 115 watercolours, drawings and other works, Artist in Exile: The Visual Diary of Baroness Hyde de Neuville, evokes a time when New York, Washington and other locales in the US of the early 19th-century were expanding rapidly, creating diverse opportunities for the baroness to cross paths with people from different occupations and economic backgrounds. Captivated by urban and rural landscapes, this largely self-taught artist roamed the city and the countryside recording buildings, streets and bridges that no longer survive, creating a crucial record of a burgeoning republic’s early days.

The show has been long in the making, with the New-York Historical Society’s drawings curator and the show's organiser, Roberta J.M. Olson, gradually discovering and acquiring caches of Neuville’s drawings for the institution and filling in gaps in the historical record of the baroness’s life. Loans from other museums flesh out the exhibition.

The show opens with a miniature self-portrait of Neuville executed in France roughly between 1800 and 1810. According to Olson, it was probably created for Neuville’s peripatetic husband Jean Guillaume Hyde de Neuville, whom she had married in 1794. Olson describes their union as a love match that endured throughout many challenges. After the baron, a royalist, became implicated in a plot to restore the French monarchy, the couple went into hiding while assuming a series of aliases; later, after Napoleon assumed power and the baron was accused of conspiring to assassinate him, they found themselves again on the run.

Anne Marguérite Joséphine Henriette Rouillé de Marigny, Baroness Hyde de Neuville, Self-Portrait from around 1800 to 1810 New-York Historical Society

Ultimately, Olson relates, the courageous baroness, travelling only with a lady’s maid, pursued Napoleon across the European continent during one of his military campaigns to seek a pardon for her husband. Catching up with Napoleon in Vienna, she managed to sway him, obtaining permission for the couple to hold onto a château that she owned near Sancerre in France's Loire Valley on the condition that they go into exile. Thus began their first sojourn in America from 1807 to 1814.

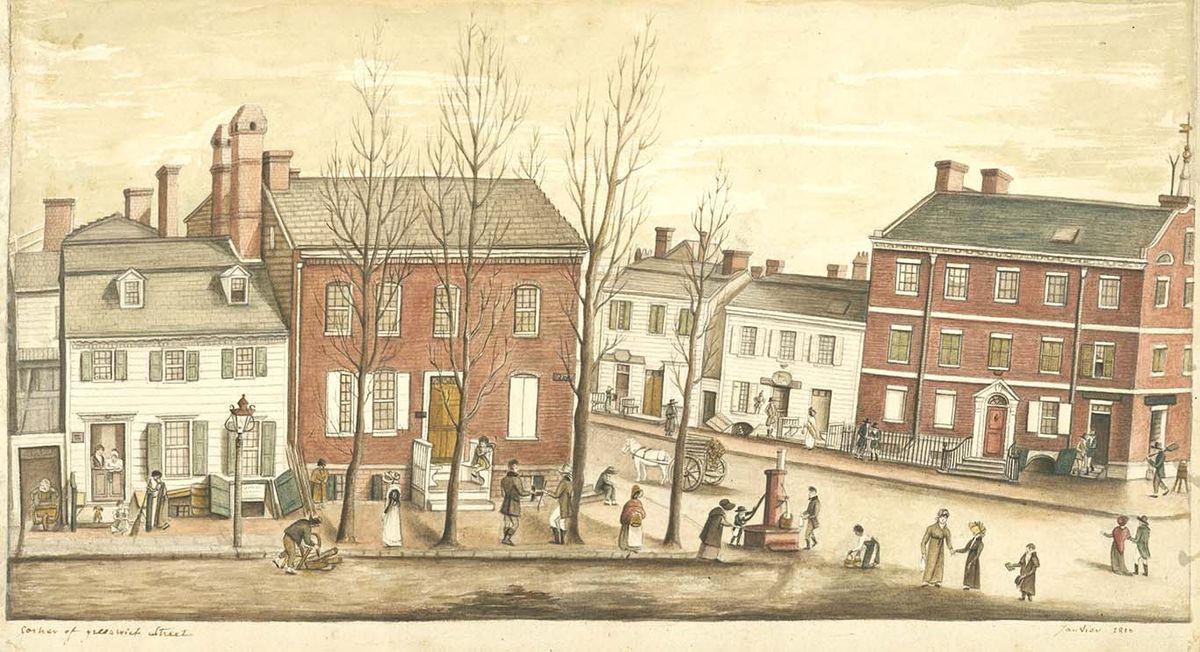

Adjusting to New York, Neuville captured busy street corners in Lower Manhattan (among them Corner of Greenwich Street from 1810) as well as institutions like churches, a prison and a rising City Hall. She and her husband also travelled through the Hudson Valley to Albany and Ballston Springs and summered in western New York while visiting a range of towns there as well as Native American settlements. (Among her portraits is a sketch of a Seneca tribesman, Peter of Buffalo.) Eventually, the couple also acquired a working farm in New Jersey where they raised sheep.

Anne Marguérite Joséphine Henriette Rouillé de Marigny, Baroness Hyde de Neuville, Peter of Buffalo, Tonawanda, New York (1807) New-York Historical Society

Anne Marguérite Joséphine Henriette Rouillé de Marigny, Baroness Hyde de Neuville, The Cottage, New Brunswick, New Jersey (1815), a rendering of the small house that the artist and her husband acquired along with a working farm New-York Historical Society

“They become part of the intelligentsia and sort of movers and shakers in downtown New York,” Olson says. “And they also have a house in the country because they are very much Enlightenment people and they both believe in the nobility of work—they celebrate labour.”

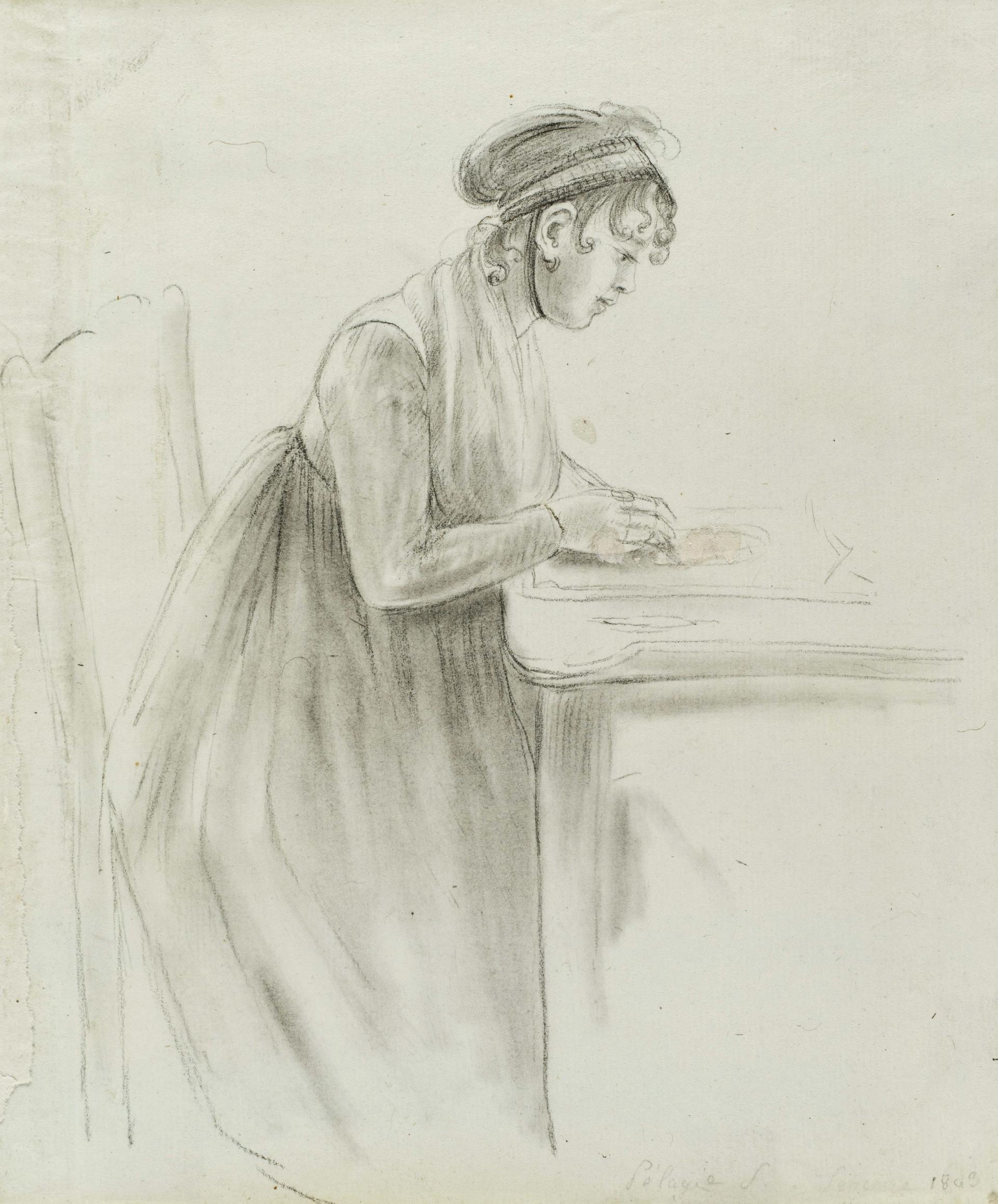

The Neuvilles were also instrumental in establishing a bilingual Economical School in New York for French and Caribbean emigrés and for adults and children who could not afford an education. Neuville executed a series of sketches of the students, among them Pélagie Drawing a Portrait (1808). “One of the main courses that they taught there, other than history, math, reading and writing, was drawing, because drawing was one of the major forms of communication,” Olson notes.

Anne Marguérite Joséphine Henriette Rouillé de Marigny, Baroness Hyde de Neuville, Pélagie Drawing a Portrait, from the Economical School Series (1808) New-York Historical Society

Napoleon’s defeat and exile to Elba in 1814 prompted the couple to return to Europe. (Always in the thick of things, the Neuvilles at one point travelled to Italy on a secret mission to warn of Napoleon’s plan to escape from Elba.)

After the second Restoration brought Louis XVIII to the throne, the baron was rewarded for his royalist labours and was appointed a minister plenipotentiary to the US. Returning to America in 1816, this time the Neuvilles set up a diplomatic residence in Washington, DC and became acquainted with President James Madison and his wife, Dolley.

Anne Marguérite Joséphine Henriette Rouillé de Marigny, Baroness Hyde de Neuville, Washington City (1820), a view of the White House and other federal buildings New York Public Library, Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs

“Washington was muddy and there were farmhouses and cattle were running around in the street, which everyone complained of,” Olson says. “It was really a wasteland. So they became the nexus of the cultural, political and social world there.” Eventually, Neuville’s Saturday night suppers and balls came to replace Dolley Madison’s Wednesday night “jams” or “squeezes” at the White House, the curator notes. Neuville’s drawings and watercolours of the presidential mansion and other federal buildings meanwhile captured the city’s still-undeveloped quality.

After another stay in France in 1820, the couple returned to the US for the final time, arriving in 1821. Again they become social magnets, received at the White House and hosting their own soirées. Armed with her drafting tools, Neuville recorded an Indian War Dance performed for President James Monroe with thousands in attendance during a visit by a delegation of Plains Indian leaders. In the upper background she sketched President Monroe with four of his guests, including the baron with a feathered bicorne hat.

Anne Marguérite Joséphine Henriette Rouillé de Marigny, Baroness Hyde de Neuville, Indian War Dance for President Monroe, Washington, DC (1821) Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum

“There are several different written records of it, but hers is the only visual record” of the dance, Olson says. “These people were dressed in Plains Indian gear, and that really excited her because it was so authentic.”

In 1822, the couple left the US to resettle in Paris and at the baroness’s country estate at L’Estang, near Sancerre.

Much of Olson’s information about Neuville’s life was drawn from a memoir that the baron left behind that was subsequently published by his nieces. He seems to have drawn heavily from a diary belonging to his wife that apparently did not survive, and other gaps are filled in by the artist’s letters.

“She was really, really quite amazing,” Olson says. “In a mixed discussion of female rulers [with the future president John Quincy Adams and his wife, Louisa], she once said the only thing she was waiting for was for an American lady to become president of the US. So, quite a woman.”

Olson finds it significant that men and women mixed so freely on social occasions, allowing Neuville to have a voice. “At this point there was a fluidity” in American society, she says. “Remember the country was under discussion—about what forms it would take, where it was going. Things were debated a great deal and women were considered partners.”

“That would change in the late 1820s and the 30s, when they begin to separate and the men took their cigars while the women went and looked at the flower paintings or whatever,” she adds.

In the end, what may be most striking about Neuville was her tenacity in recording her observations. “She found an eloquence in her works of art to communicate what she saw—the New World, the Old World, what people she encountered, what really piqued her interest,” Olson says.

“It’s what set her on fire, what really pulled at her soul.”

• Artist in Exile: The Visual Diary of Baroness Hyde de Neuville, New-York Historical Society, 1 November–26 January 2020