When Queens Museum curators learned that a travelling Rube Goldberg exhibition was in the works in the US, they quickly resolved to host it. What better place than a museum that celebrates New York, where Goldberg came to fame as a cartoonist drawing zany, deliberately overengineered contraptions? they reasoned. “We felt it would be too painful not to bring the show here,’’ says the curator Larissa Harris.

The exhibition, The Art of Rube Goldberg, traces Goldberg (1883-1970)’s trajectory from his turn-of-the-century drawings, including the first glimmerings of his comic style, on through his years as an extremely popular syndicated cartoonist sketching outlandish inventions from the late 1920s to the 1940s. Political cartoons from the 1930s, 40s and 50s ridiculing targets like Stalin and political corruption help round out the picture.

Also examined is the influence that vaudeville had on Goldberg’s frenetic work, and how he in turn influenced Hollywood through collaborations on sets and scripts with Charlie Chaplin and The Three Stooges. Videos, family photographs and ephemera from advertisements he drew for companies like Pepsi, Pennzoil and Lucky Strike in later years complete the portrait.

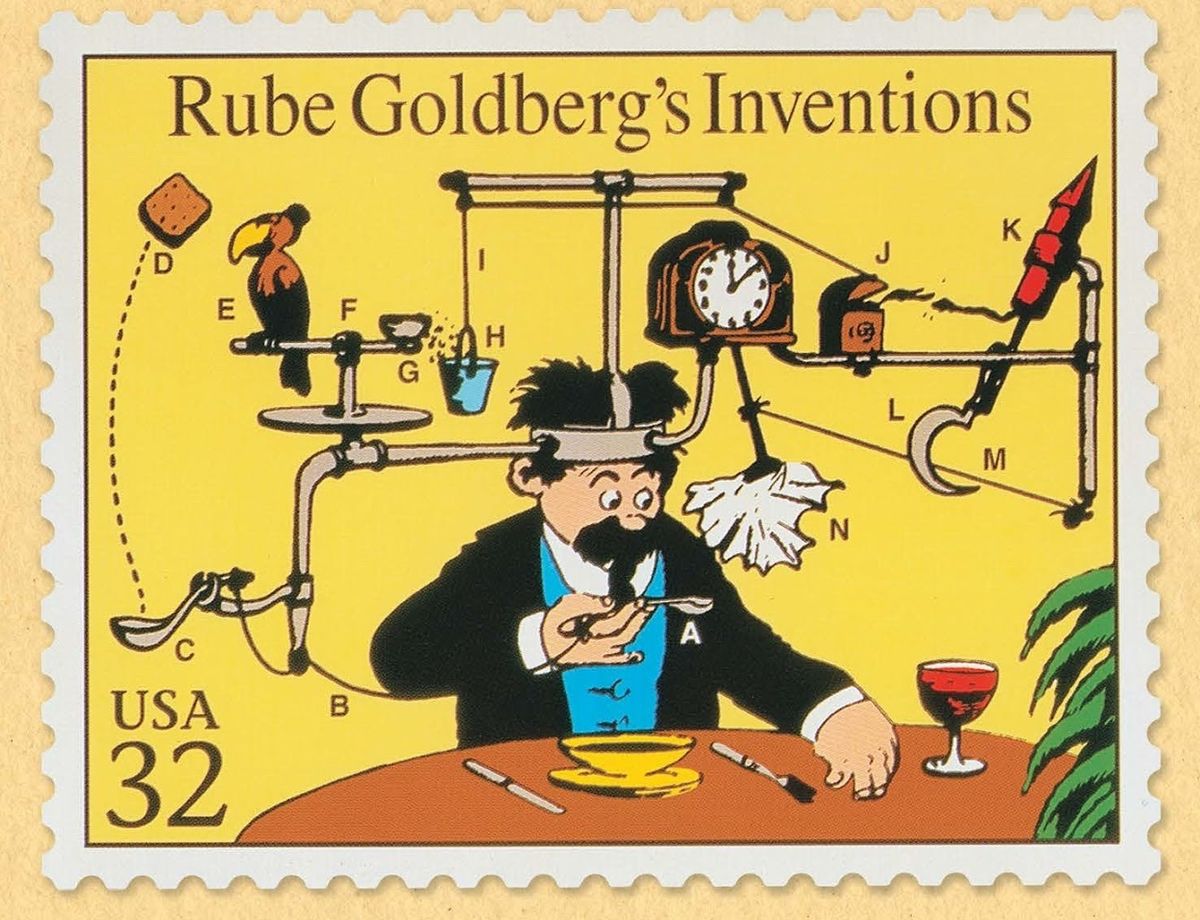

But front and center are those invention cartoons, which gave rise in the US to the label “Rube Goldberg” to describe any gadget accomplishing simple tasks in absurdly convoluted ways. According to Harris, part of the artist’s aesthetic was rooted in patent drawings minutely labelling the components of inventions from A to Z.

Galvanised by the show, the Queens Museum has commissioned its own special exhibit, an interactive machine inspired by Goldberg’s cartoons. “People think that Rube Goldberg designed machines—he did not, he made drawings,” Harris says, although the artist did earn an engineering degree before embarking on his cartooning career. “It was us thinking that they [the machines] would be impossible in reality.”

A multimedia Rube Goldbergian apparatus that the Queens Museum commissioned from Partner & Partners along with the designers Greg Mihalko, Stephan von Muehlen and Ben Cohen. Hai Zhang/Courtesy of the Queens Museum

The curators put that assumption to the test, turning to the design practice Partner & Partners along with the designers Greg Mihalko, Stephan von Muehlen and Ben Cohen. What resulted is a multimedia creation titled A Machine for Introducing an Exhibition that blends video animations with actual mechanical chain reactions.

First the user presses a big green button. An animated bird flies on a flat screen, which then triggers a real electric fan that blows on a pinwheel and activates a boot through a motor. The boot kicks over a watering can, which leads to a video of a cat leaping up and triggering yet another physical reaction. (And so on.)

The Queens Museum curator Sophia Marisa Lucas sees a link between Goldberg's inventions and creative thinking on the Internet today. “It’s the idea of limitless possibilities to almost an absurd degree,” she says. “The core idea is that in pursuit of endless convenience, new languages and new sensibilities have to be orchestrated. We have to learn how to manoeuvre in the world differently.”

Harris suggests that the show ties in well to works at the Queens Museum like its popular panoramic model of New York City and its futuristic holdings from the 1939 or 1964 World’s Fair. “We have a spirit of playfulness at the museum that this show really brings out,” she says. “Like the model of the city, it brings joy.”

• The Art of Rube Goldberg, Queens Museum, New York, until 9 February 2020