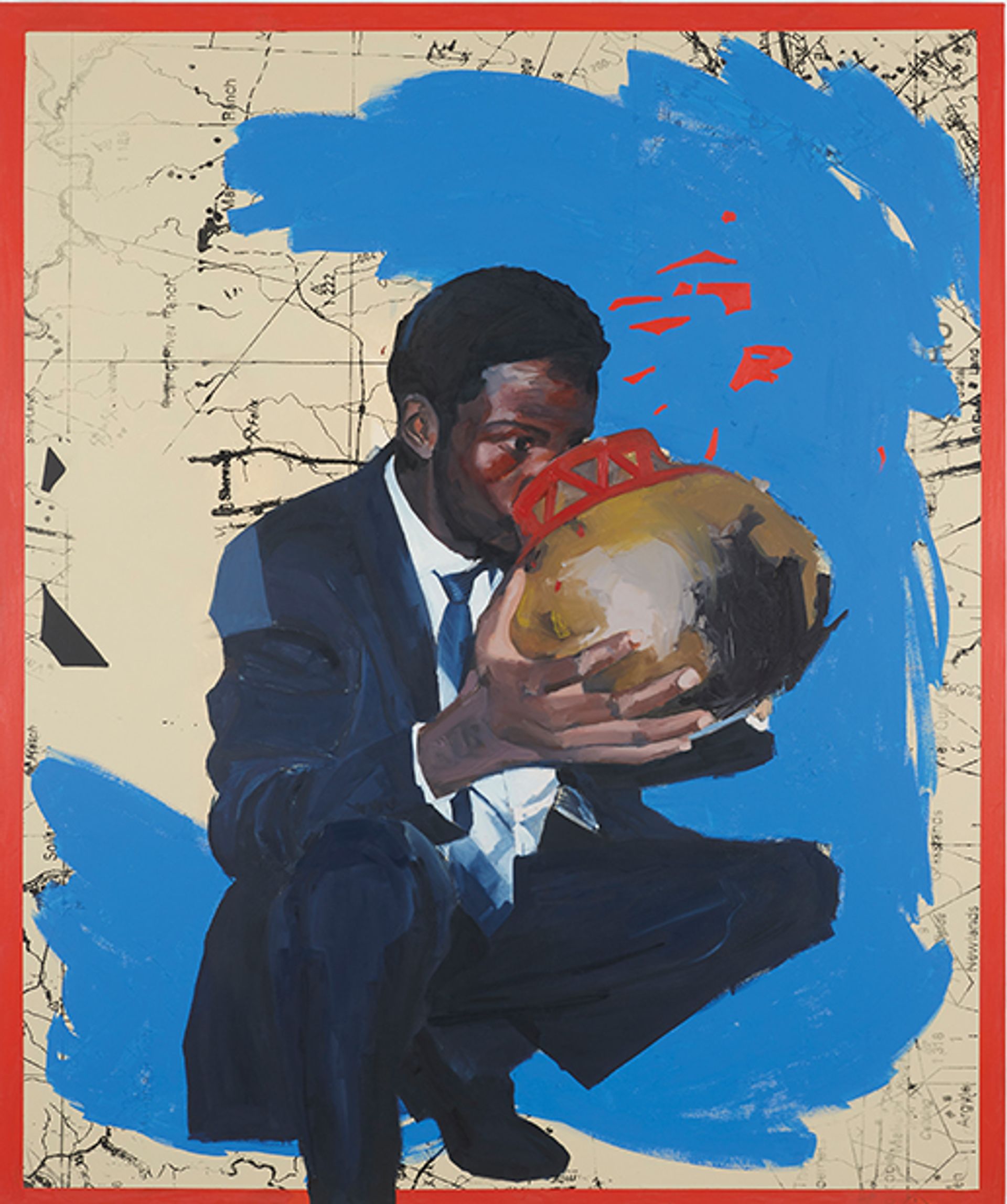

Bira (2019) by Kudzanai-Violet Hwami appears in the artist’s first institutional solo show at Gasworks Photo by Andy Keate, Courtesy of the artist and Tyburn Gallery

Recent research suggests that, for African artists, it pays to be female. Contrary to markets in the US and Europe where male artists command higher prices, four women lead the auction table: Marlene Dumas ($6.3m), Julie Mehretu ($5.6m), Irma Stern ($4m) and Njideka Akunyili Crosby ($3.4m). This correlates with an ArtTactic report, published in July, on auction sales of Modern and contemporary African art between 2016 and 2019, which found that the average price for female artists was consistently higher than for males. In 2019, women fetch on average $91,338, compared with $19,555 for men. However, the number of lots sold by male artists in 2019 far outweighs those by women: 680 versus just 131.

Despite the positive strides being made by women in this field, though, Hannah O’Leary, the head of Modern and contemporary African art at Sotheby’s, sounds a note of caution. “This story is more about African artists being undervalued. If you look at the market as a whole, Africa is still so underrepresented: it’s less than 1%,” she says. “We have a long way to go before we actually see a true representation of diversity, but we are witnessing the beginnings of that.”

Indeed, being pale and male still wins in the art world. But, if the number of exhibitions on women from Africa on show this week in London is anything to go by, significant steps are being made to redress the glaring imbalances.

Mary Sibande has her UK debut at Somerset House, which features I’m a Lady (2009) © The artist

The South African photographer Mary Sibande has her first solo show in the UK at Somerset House (until 5 January 2020), while the non-profit space Gasworks is hosting Kudzanai-Violet Hwami’s first ever institutional solo show. She is one of four artists to represent Zimbabwe at the Venice Biennale this year and has just been signed by Goodman Gallery. Further afield, Nigerian-born Otobong Nkanga has her first UK museum show at Tate St Ives.

As the established parameters of culture are dispatched with, private collectors are also looking to fill the gaps in their collections. Prices are duly rising for female artists from Africa. The young Nigerian artist Njideka Akunyili Crosby is a case in point. According to the Wall Street Journal, her paintings—usually executed on paper—were selling for $3,000 just five years ago. Two years after being signed by the Victoria Miro gallery, Akunyili Crosby first appeared at auction in September 2016, when an untitled work from 2011 sold for nearly $100,000 with fees. Within two months she broke the $1m mark and within six months her work was selling for more than $3m. She achieved her record for a richly layered botanical collage, Bush Babies (2017), at Sotheby’s in New York in May 2018.

Such a leap at auction does not always equal long-term success, however, and, for women in particular, it can be difficult to thrive in mid career. Even with institutional support, Akunyili Crosby told the Wall Street Journal last year: “My friends tell me I should just be happy my works are selling, and I am. It’s scary how vulnerable I still feel.”

Akunyili Crosby appears in an all-female group exhibition, organised by the British artist Isaac Julien, at Victoria Miro’s space in Hoxton. Its title, Rock My Soul (until 2 November), is borrowed from a book by the black feminist scholar Bell Hooks on black people and self-esteem. Other artists include the South African visual activist Zanele Muholi, the Kenyan artist Wangechi Mutu and the Gambian-British photographer Khadija Saye, who died in 2017 in the Grenfell Tower fire in London. Victoria Miro is offering a portfolio of nine silkscreens by Saye, priced between £10,000 and £25,000, with proceeds benefiting the Khadija Saye IntoArts Programme.

Silkscreens from Kadija Saye’s series Dwelling: In this Space we Breathe (2017-18) © The Estate of Khadija Saye

The exhibition combines new and historical works. Julien points out that while some of these artists have been working for an incredibly long time, what is new is “the presence of black, women and non-binary artists in exhibitions at this scale”. He adds: “Are these exhibitions correctives? Or merely stating the obvious?”

For Liza Essers, the director of South Africa’s Goodman Gallery, which opens its first space in London this week, it is a question of visibility. Since taking the helm ten years ago, she has signed 34 artists, 19 of whom are women. She is also championing parity at Frieze London, with half her six-artist stand devoted to work by women: Sue Williamson, Tabita Rezaire and Kapwani Kiwanga. Prices start at an affordable €8,000.

Goodman gallery’s first London show is an exhibition centred on the idea of social repair. Here, too, the gender split is roughly even—ten of the 22 artists are women. The show’s title, I’ve grown roses in this garden of mine, takes its moniker from the South African artist Gabrielle Goliath’s latest work, This song is for… (2019), priced at $70,000). The 12-channel video consists of a cycle of songs chosen by survivors of rape.

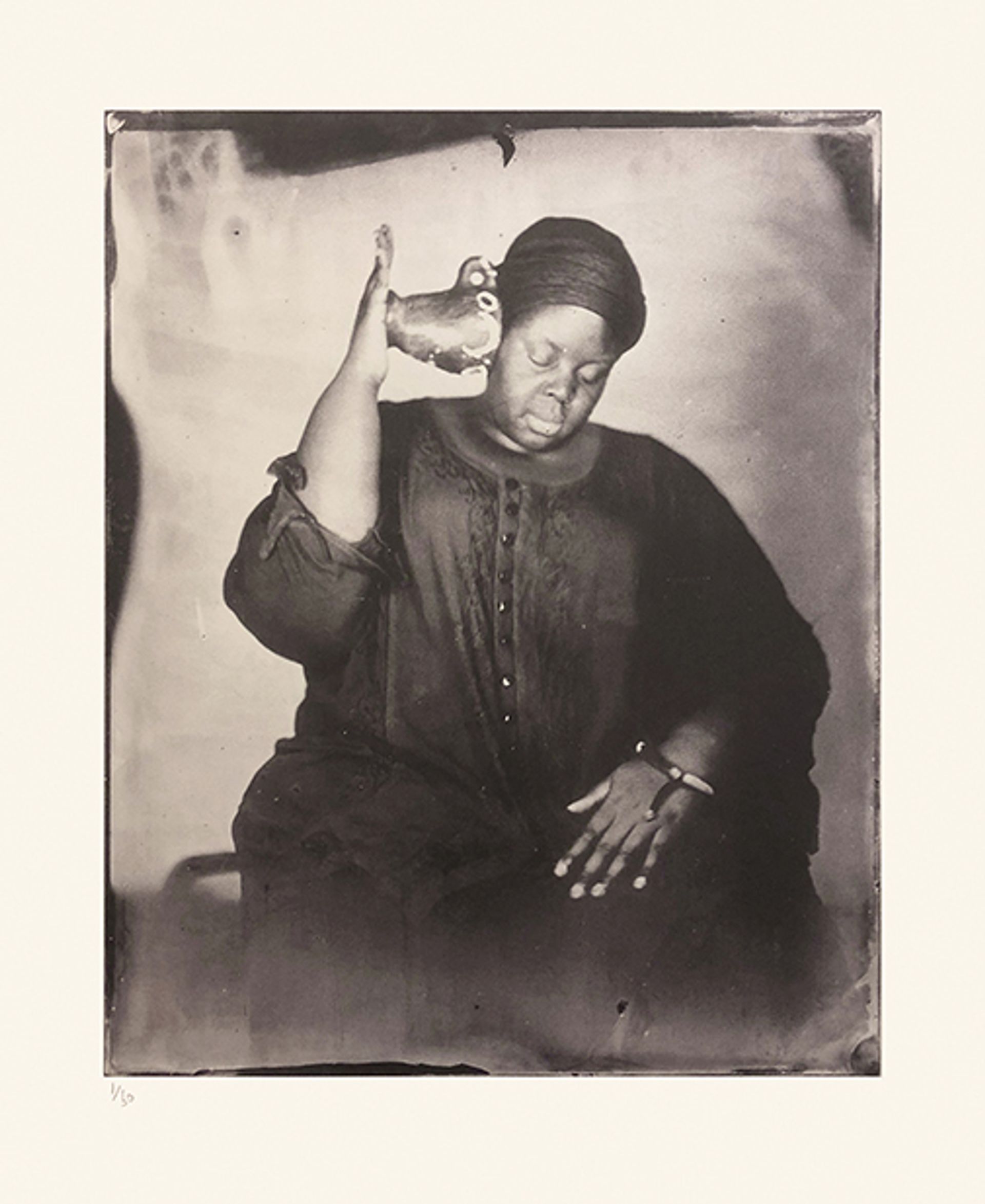

Zanele Muholi’s Cebo II; Philadelphia (2018) will feature in Isaac Julien’s all-female show Rock My Soul at Victoria Miro gallery Courtesy of Stevenson, Cape Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York

Gender-based violence is an urgent issue in South Africa and many artists are grappling with it in their work. Speaking last month at the home of the Johannesburg collector Pulane Kingston, who estimates that 90% of her collection consists of works by female artists, Mary Sibande described her depression in the days following the brutal rape and murder of 19-year-old Uyinene Mrwetyana in a post office in Cape Town. “For the first time I felt scared to be a woman,” she says. “South Africa is a violent place and I’m at the point where I want to know why.”

Sibande’s Somerset House exhibition, I Came Apart at the Seams, hosted in partnership with the 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair, marks the first time a woman has been chosen for the main exhibition. The fair’s founder Touria El Glaoui is striving for balance; this year 1-54 has a roughly equal number of solo shows by female and male artists, including a special commission of photographs by the Ethiopian artist Aida Muluneh. But inequality still persists in the overall number of artists at the fair, as just 31% are women. But “these numbers are improving each edition”, El Glaoui says.

There is a genuine sense that institutions now want to build global connections

At Frieze London, female African artists are becoming more visible. London’s Tiwani Contemporary makes its debut at the fair with a solo presentation of figurative paintings by Dagenham-born Joy Labinjo that draw on her British-Nigerian heritage. Labinjo has a show due to open at the Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art in Gateshead on 19 October.

Lagos-born Maria Varnava, who founded the gallery in 2011, cites the Tate establishing its Africa Acquisitions Committee the same year as a turning point. “There is a genuine sense that institutions now want to build global collections,” she says.

Growing a pan-African collector base for contemporary art is a necessary next step, Varnava believes. “We need that local patronage. It’s not a matter of survival: it’s a matter of growth and growth happening equally,” she says.