When we visit a career-surveying exhibition of a canonic artist, it is not necessarily the case that the approach would have seemed familiar or appropriate to that artist. In the case of William Blake, he belonged to the first generation of British artists who presented their work solo, in the form of what we would call a retrospective. Most of the artists of the time who did so were driven to it out of resentment and self-justification. The first to have done so appears to have been Nathaniel Hone in 1775, after the Royal Academy rejected his vicious satire on its president, Reynolds. In 1804, Turner opened a permanent gallery to display his own works behind his house on Harley Street and Queen Anne Street.

Blake, perhaps inspired by the great success of Turner’s enterprise, gave way to long-standing resentment at the principles by which the academy hung his works. He mounted an exhibition in 1809 of 13 works. It proved one of the most famous disasters in British art, attracting hardly any visitors and no buyers. The public was put off by the lowly setting of Broad Street, by the absurdly high price Blake insisted on charging, and by the eccentricity of Blake’s art. The solitary review called Blake a madman. An artist who comes off worse by insisting on his worth in the face of a sceptical or uninterested market is nothing new in British art. Hogarth, in the 1750s, had had a grand history painting, Sigismunda Mourning Over the Heart of Guismondo (1759), rejected by a patron and refused to sell it for less than the huge sum of £500. What is new in the relationship between Blake and us, as it were, is that for the first time we appear to be able to look at an artist’s work in the way that he clearly aspired to.

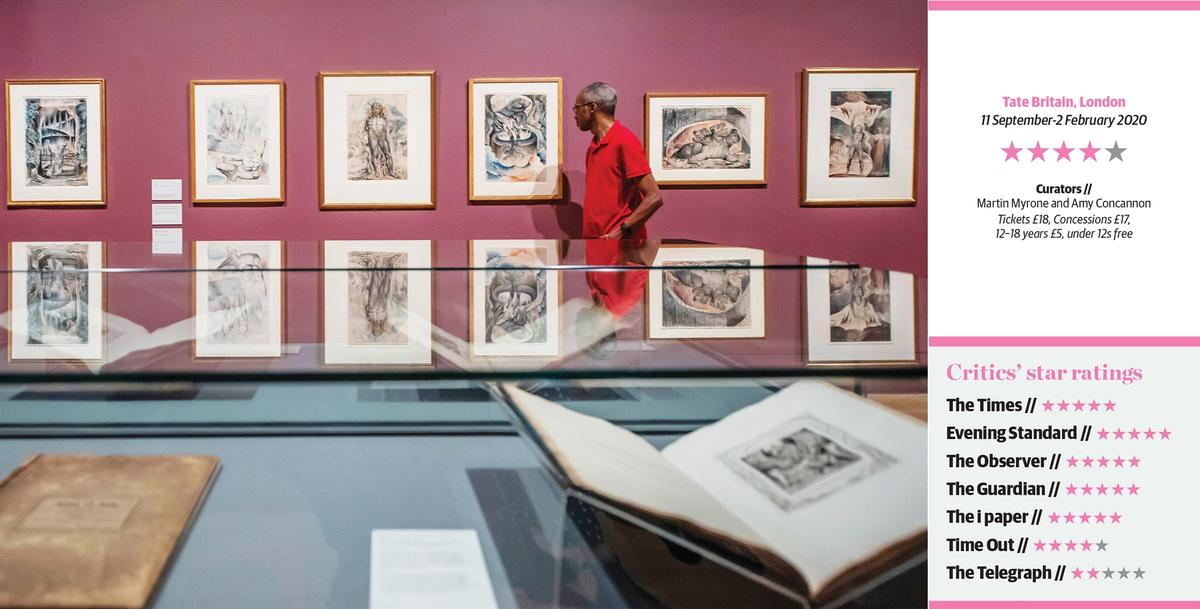

The intention of Tate’s substantial Blake survey is to show us the artist in his own time, as a product of specific circumstances. In places, we are to look at the work as Blake’s contemporaries might have looked at it. A partial reconstruction of the exhibition of 1809 is attempted, with daylight effects plunging some of Blake’s darkest paintings into stygian gloom, occasionally interrupted by projections showing the more brilliant colours the works originally might have possessed. There is an excellent commitment to show Blake’s work as it originally came to an audience, not just in framed works hanging on a wall. People would have bought Blake’s engravings after different artists, or original works; would have read printed books with his engraved illustrations, original or otherwise; would have bought the luxurious and densely idiosyncratic illuminated books, turning the pages very carefully. They would have seen his work as part of miscellaneous exhibitions at the Royal Academy and other institutions, or, if very lucky, in a solitary display in 1809.

The different ways in which an audience came to Blake through Stedman’s Narrative of a Five Years’ Expedition, the Canterbury Pilgrims print, the Jerusalem illuminated volume and the Ghost of a Flea (1819-20) painting is difficult for a modern display to reproduce. Everything tends to be flattened into what was the smallest, though most prestigious, part of Blake’s professional life, the framed image hanging on the wall. Tate has done very well to show the full range of pictorial endeavour, in vitrines containing opened books, as well as projections of unrealised work.

Of course, it is impossible to return a 2019 audience to the state, at once more innocent and more knowing, of a Georgian one. The “daylight” in the 1809 room here is, of course, powered by electricity, and the disagreeable, brilliant illuminations make two of Blake’s greatest paintings look like nothing on Earth. (The Satan Calling up his Legions adjacent is left in total darkness.) Some of the factual aspects we are enlightened about, such as Blake’s fees and earnings, would have been known to very few people at the time. I doubt that many people, either, would have known or much cared about the processes of creation, or what, exactly, Catherine Blake contributed—how many visitors to Tate Modern’s Olafur Eliasson show currently could give a confident account of how the artist’s work is funded, to what extent, and how it is put together and by whom?

What the contemporary audience would have been able to discuss was Blake’s position in relation to the art of his time. The Tate exhibition, tending towards historical elucidation rather than critical judgement, rather neglects this. Although the exhibition nods towards some contemporaries, and notes that Fuseli owned one of Blake’s books, his pictorial language is still presented as a unique and unprecedented creation. In fact, a carefully chosen selection of works, not just by Fuseli but by James Barry, James Jeffereys, perhaps John Hamilton Mortimer, the sculptor Thomas Banks and others, would show that advanced taste would have found much of Blake’s invention palatable. The anatomical distortions and painful posing in abstruse mythological contexts can easily be paralleled in works from Fuseli’s circle from the 1770s onwards. How Blake worked, and how much he was paid, would have been less important than what he, evidently, had looked at. This, however, comes lower down in this exhibition’s priorities.

Blake then and now

The critical response to the exhibition has divided neatly into those who engage with Blake in his time, and those who want to draw lessons for our historical moment. For Jonathan Jones in the Guardian, Blake was not just a “self-taught genius who comes out of the popular culture of 18th-century London” but a “feminist”, an “anti-racist” and a “pacifist”. For Matthew Collings in the Evening Standard, one image evoked “a Jeremy Corbyn god who rolls a sun along the ground as if he’s rolling away Boris Johnson’s no deal”. (Considering the image is of Blake’s cosmic tyrant Urizen, the Leader of the Opposition may have a case here for gross defamation). On the other side, Rachel Campbell-Johnston of the Times stressed “the radical politics of his revolutionary era” and characterised him as an artist of London, as much as of mythologies. Laura Freeman in the Spectator presented him as an artist who balanced historical realities and his own fantasy, “Nelson and Lucifer, Pitt and the Great Red Dragon, chimney sweeps and cherubim, the Surrey Hills and Jerusalem in ruins, the alms houses of Mile End and the vast abyss of Satan’s bosom.” Almost all the reviews regarded Blake with rapture. Only Alastair Sooke of the Daily Telegraph criticised the idea that Blake might be an “artist for the 21st century” and suggested this aim might not be compatible with the exhibition’s historicising goals. Nowhere in the critical response was there an appropriate humble acknowledgement that when a great artist rises in unpropitious circumstances, the critic is quite likely to fail to notice, to praise a Martin Archer Shee instead of a Blake, or, still, to observe like the solitary critic of Blake’s 1809 exhibition that these are “badly drawn… wretched pictures…[by] an unfortunate lunatic”. It’s quite easy to recognise greatness, two centuries on.

We are never going to look at Blake with innocent eyes. One interesting development of the exhibition: Tate has thought it necessary to warn us that one vitrine contains an image of “the brutal treatment of an enslaved person”. Moral judgements on art’s decency are nothing new, but this one is so remote from anything the anti-slavery movement might have considered as to make one wonder whether we can, in fact, be said to be looking at these images at all rather than our own projections.

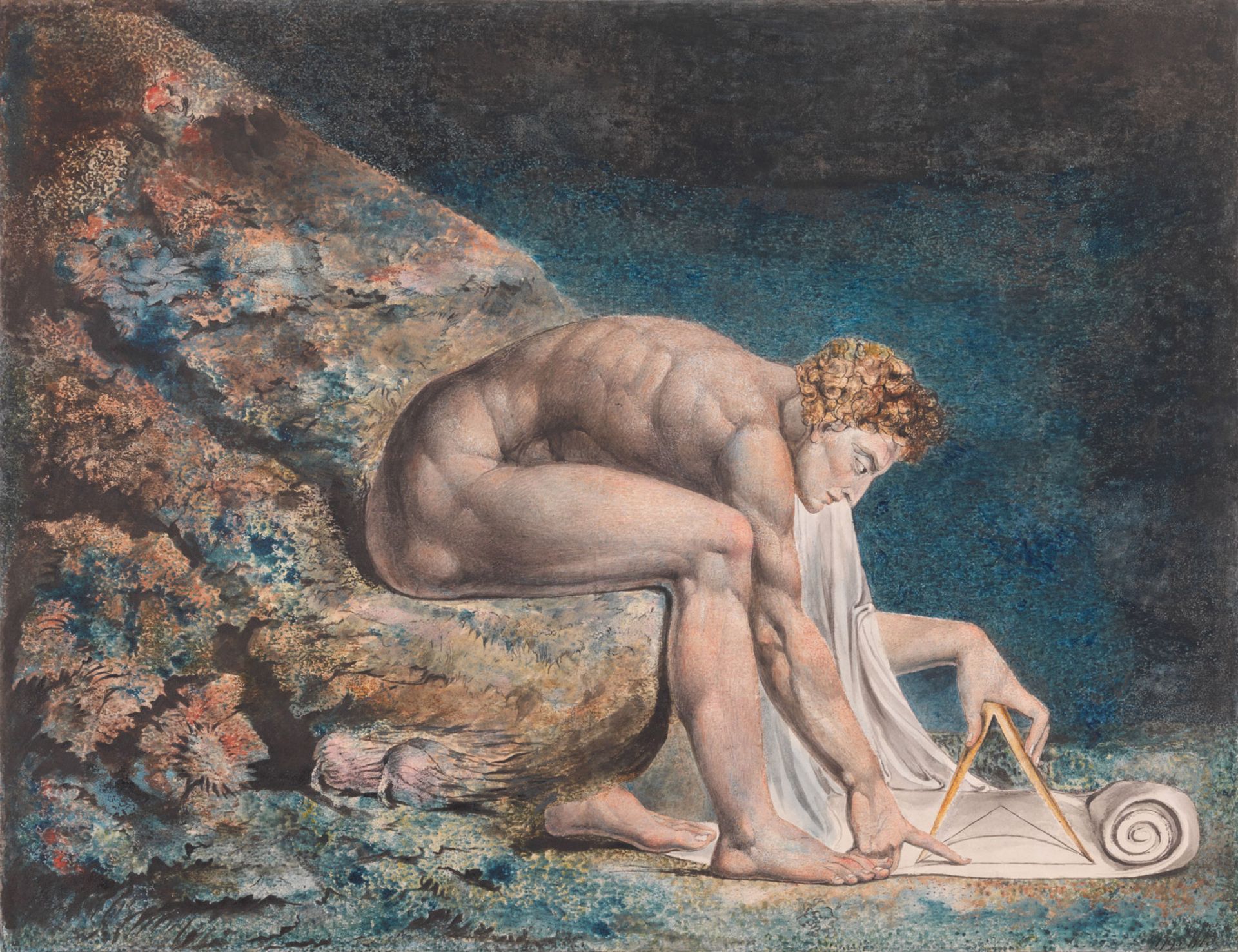

Perhaps the most successful of the rooms in this exhibition is an apparently unambitious one: the 12 large colour prints made for Thomas Butts, including the famous Nebuchadnezzar and Newton. Unobtrusively well-lit, hanging on an ideal dark colour, they present their echoes and meaning without comment, for us to contemplate and engage with on our own terms, whether that is historicising or modern day, learned or innocent. I guess that’s all that Blake ever managed to do.