He recalls the young preacher pulling up to the curb in a blue Pontiac and then entering the Montgomery, Alabama barber shop, ready for a haircut. “Heck,” the barber, Nelson Malden, remembers thinking. “I could knock him out in 15 minutes.” He asked the customer for his name. “Martin Luther King,” the young man replied.

In the months that followed, Malden would cut King’s hair seven or eight more times, noticing that the minister always left the shop without leaving a tip. Humorous cajoling followed, to no avail. “We had a very good relationship,” Malden recalls with amusement.

That memory, dating from 1954, is among the poignant stories recounted by veterans of the Civil Rights Era in Voices of Alabama, an online digital platform of videos, vintage photographs, maps and timelines launched today by the World Monuments Fund, the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute and the Alabama African-American Civil Rights Heritage Sites Consortium.

The stories flow from 20 sites championed by the consortium for having played significant roles in the African American struggle for freedom, from the Civil Rights campaigns of the 1950s and 60s on back to the Reconstruction era. In 2018, the World Monuments Fund added the consortium to its biennial watch list of sites around the globe whose heritage needs protection.

“There’s a sense of urgency in collecting these stories,” says Priscilla Hancock Cooper, the project director for the consortium. “The Civil Rights generation is aged and dying.” By amplifying voices like Malden’s through the online platform, she says, “the hope is getting a new generation engaged.”

Some of the 20 sites are not yet open for tours or lack a website, Cooper noted. The consortium hopes that the online platform will spread awareness so that each one is nurtured and finds the financial means to become sustainable.

Malden’s barber shop is on the ground floor of the Ben Moore Hotel, which opened its doors to African American customers soon after it was built in 1945 and was the site of historic meetings between representatives of the black and white populations of Montgomery. Malden notes that performers like Duke Ellington, Ray Charles and Ike and Tina Turner would stay there when they came to town, and that Civil Rights campaigners used it as a starting point for a massive march to the local courthouse.

Marchers gathering outside the Ben Moore Hotel in Montgomery, Alabama Spider Martin

Another video offers testimony from Joyce Parrish O’Neal, a member of the Brown Chapel AME Church in Selma, Alabama, built in 1908 and the gathering point for the Selma-to-Montgomery Civil Rights marches. After hearing chilling screams and horses’ hooves, O'Neal recalls watching state troopers on horseback, armed with clubs and tear gas, pursuing protest marchers fleeing toward the church during the Bloody Sunday crackdown on 7 March, 1965. “I remember seeing the horses ride up the steps, which was terrible for me because this was a sacred place for me,” she says. “I was baptised as an infant right at that altar.”

Demonstrators beginning the march from Selma to Montgomery outside Brown Chapel AME Church James Barker

Valda Harris Montgomery reminisces in anther video about growing up in the Dr Richard H. Harris Jr House in Montgomery, dating from the turn of the 20th century. She remembers her father hosting figures like King, the Reverend Ralph Abernathy and the Reverend Joseph Lowery. “It was a safe place to come and discuss, someplace they could relax,” Montgomery says. The Civil Rights leaders would troop to the top floor of the house, draft plans for protests and take them down to students waiting below, she says.

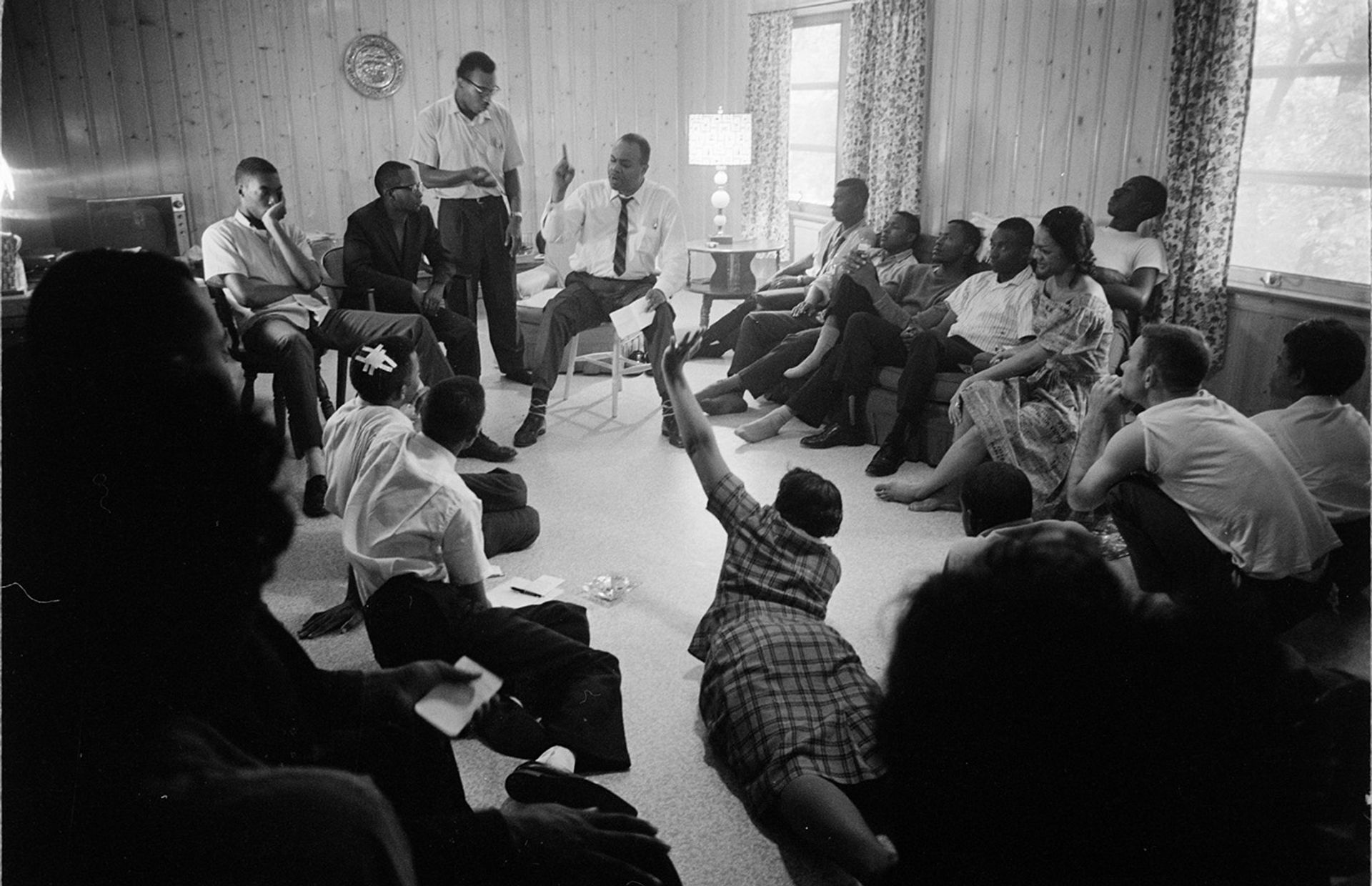

Most vividly, she recalls how 33 Freedom Riders—the activists who rode interstate buses into segregated Southern cities—took refuge in her home after the National Guard rescued them from a white mob at the Greyhound bus station and transported them to safety in a truck.

Freedom Riders plan their next step at the Dr. Richard H. Harris House in Montgomery Paul Schutzer/The LIFE Picture Collection via Getty Images

Another video centres on the 1889 Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, where King became pastor in 1954 and rallied churchgoers behind the local bus boycott by African Americans late the following year. Ralph Joseph Bryson, a longtime member of the church, recalls King applying for the pastor’s job. “We interviewed a number of young men, but when Martin came, he gave a sermon—when he finished, we said: there’s no sense in going any further. He was our man.”

The Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in the pulpit at Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery Courtesy of Alabama Department of Archives and History

The online platform was launched with support from Jack Shear and the Ellsworth Kelly Foundation as well as Friends of Heritage Preservation.