ImageNet, one of the largest, publicly accessible online databases of pictures, has announced that it will remove 600,000 images of people stored in its system.

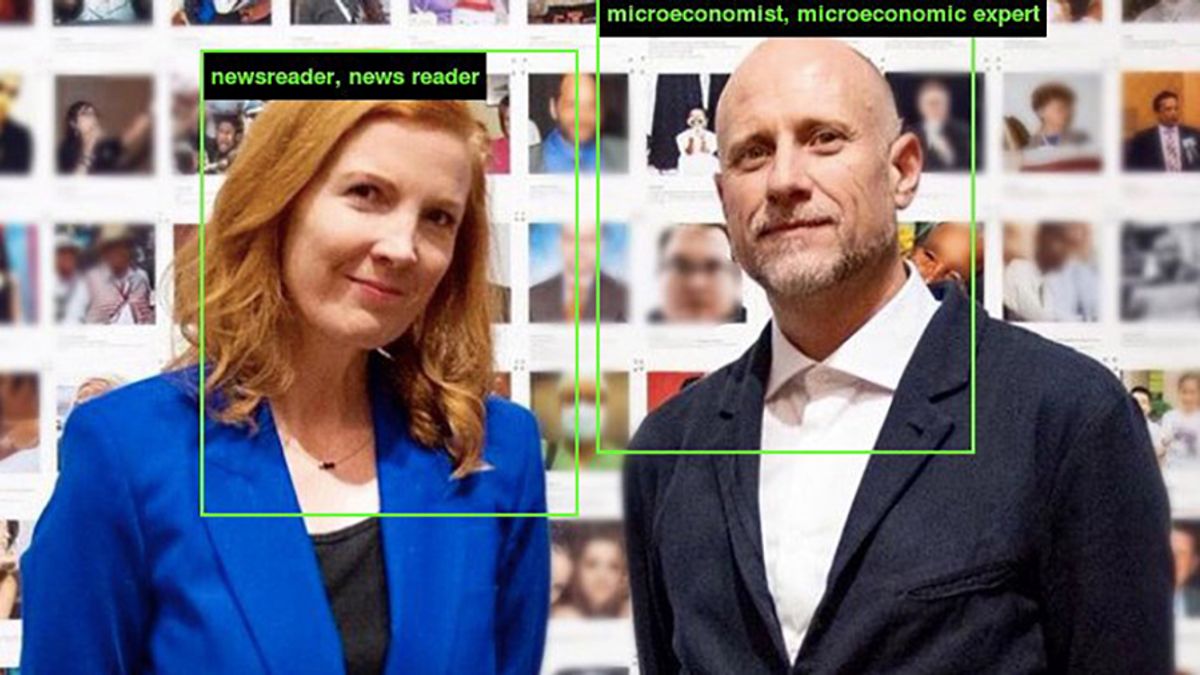

The news follows the launch of an online project by the artist Trevor Paglen and the AI researcher Kate Crawford who revealed the troubling and often racist ways in which the artificial intelligence used by ImageNet categorises people.

Paglen and Crawford’s ImageNet Roulette went viral this month as users uploaded photographs of themselves which were then classified by ImageNet technology.

While white people are regularly assigned wildly inaccurate job descriptions—one editor for the Verge, for example, was categorised as a “pipe smoker” and a "flight attendant"—for people of colour, the technology is far more sinister with social media users reporting that they had been described with racist slurs and other highly-offensive terms.

As the database is widely used to train machines how to “see” and law enforcement agencies, private employers and schools in the US are increasingly using facial-recognition technologies for security purposes, the implications are far-reaching.

“As AI technology advances from research lab curiosities into people’s daily lives, ensuring that AI systems produce appropriate and fair results has become an important scientific question,” ImageNet says in a statement posted on its website.

Although the statement does not refer to Paglen and Crawford’s online art project, it was published just five days after the opening of the duo’s Training Humans exhibition at the Fondazione Prada’s Osservatorio venue in Milan (until 24 February 2020), which brought renewed attention to ImageNet’s flawed categorisation systems.

“This exhibition shows how these images are part of a long tradition of capturing people’s images without their consent, in order to classify, segment, and often stereotype them in ways that evokes colonial projects of the past,” Paglen says.

Racist technology

ImageNet was created in 2009 by researchers at Princeton and Stanford universities. It assembled its collection of pictures of people by scraping them off the internet from websites such as Flickr. These were then categorised by Amazon Mechanical Turk workers. The prejudices and biases of these low-paid, crowd-sourced labourers are inevitably reflected in the AI system that they helped create.

ImageNet says it has been “conducting a research project to systematically identify and remedy fairness issues that resulted from the data collection process” for the past year. It has identified 438 categories of people on its database, which are “unsafe”, defined as “offensive, regardless of context.” A further 1,155 labels are “sensitive” or potentially offensive, depending on the context in which they are used. All the images associated with these categorisations are now being removed from the database.

In response to ImageNet’s announcement, Paglen and Crawford said that ImageNet Roulette had “achieved its aims” and would no longer be available online after Friday 27 September.

“ImageNet Roulette was launched earlier this year as part of a broader project to draw attention to the things that can—and regularly do—go wrong when artificial intelligence models are trained on problematic training data,” the duo write on the project’s website.

“We created ImageNet Roulette as a provocation: it acts as a window into some of the racist, misogynistic, cruel, and simply absurd categorisations embedded within ImageNet. It lets the training set ‘speak for itself,’ and in doing so, highlights why classifying people in this way is unscientific at best, and deeply harmful at worst.”

“The research team responsible for ImageNet [has now] announced that after ten years of leaving ImageNet as it was, they will now remove half of the 1.5 million images in the “person” categories. While we may disagree on the extent to which this kind of “technical de-biasing” of training data will resolve the deep issues at work, we welcome their recognition of the problem. There needs to be a substantial reassessment of the ethics of how AI is trained, who it harms, and the inbuilt politics of these ‘ways of seeing.’ So we applaud the ImageNet team for taking the first step.”

“ImageNet Roulette has made its point—it has inspired a long-overdue public conversation about the politics of training data, and we hope it acts as a call to action for the AI community to contend with the potential harms of classifying people,” they say.

• Trevor Paglen and Kate Crawford’s investigative article about ImageNet, “Excavating AI”, is available here