They were among the world’s most famous and pioneering of artistic couples. The ending of Marina Abramovic and Ulay’s relationship—after the pair walked towards each other across almost 6,000km of the Great Wall of China—resulted in one of the most epic performances the art world had ever seen. Yet no one in China has had the chance to witness the work, until now.

This month, the Serbian performance artist will see her photographic performance The Lovers (1988) exhibited for the first time in China at Shanghai PhotoFairs, now in its sixth year.

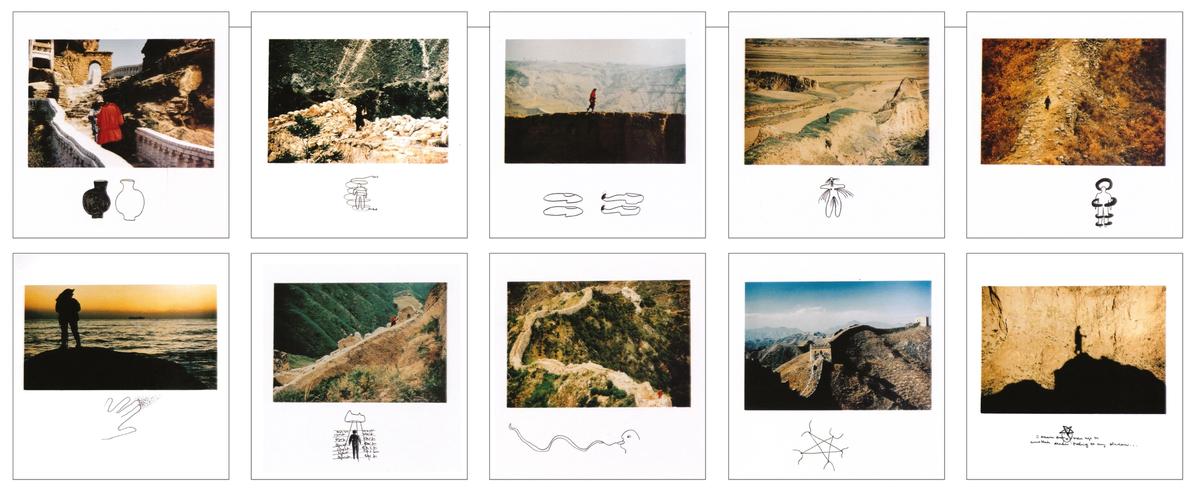

Speaking to The Art Newspaper, Abramovic remembers the journey as “an incredible physical and spiritual experience”. In April 1988, Abramovic and fellow artist Ulay started from opposite ends of the Great Wall of China—the eastern Gulf of Bohai on the Yellow Sea and the western Jiayu Pass in the Gobi Desert—covering 5,995km between them. “We went to different ends, and then there was this huge distance,” she says. “All we could do was walk towards each other.”

Abramovic met Ulay in 1975. They lived in a Citroën van for more than ten years, merging both their personal lives and artistic practices. Their symbiotic performances, which involved kissing and hitting each other, or he shooting at her with a bow and arrow, or the two of them standing naked while viewers passed between, became viral events in the art world.

“Looking back, this relationship was extremely important for the history of performance art,” Abramovic says.

Marina Abramovic © Nils Müller and Wertical

The pair had planned The Lovers for years. They aimed to walk from either end of the wall, and, when they met, immediately marry. But it took eight years to acquire permission from the Chinese government. By the time they embarked on the journey, their relationship had dissolved.

“It was supposed to be a grand romantic idea, and it was powerful for us,” Abramovic says. “But we thought it was one straight line that we could walk along, each of us alone, and camp out on the wall every night.”

In reality, Abramovic found herself circumnavigating piles of rubble. “It was so difficult, because only parts of the wall were renovated for tourists. The rest of it, around the mountains, was a ruin,” she says.

The Chinese government provided Abramovic with a 27-year-old translator and a host of soldiers. “The translator was sent to me as punishment,” Abramovic recalls. “There was a Chinese delegation in New York, and he was sent as a translator. But he became fascinated by people breakdancing on the streets. He took photographs, Xeroxed them and turned them into a booklet. It was forbidden in China, but it became very hip with the youngsters, and everyone had this little book about breakdancing. As punishment, they sent him to walk the Great Wall of China with me. He arrived in a grey suit and bad, broken shoes. I had to give him my clothes and equipment. He really didn’t like me. For the first two months, we hardly talked. And then we became really good friends.” The translator took the photographs that are due to go on show at Shanghai PhotoFairs.

"The energy you experience from the wall seemed perfect to us to make a work of art. And it was: it was painful, it was hardship, but it made me merge with the landscape."Marina Abramovic

Abramovic recalls being regarded with disbelief whenever she met the rural Chinese who lived by the wall. “A woman away from her children and her husband, walking the wall alone? They thought it was impossible,” she says. “Every time I came to a village, the entire village would come and look at me. The older women would very gently hold my nose, because I have a big nose, and it was red and swollen. They thought, if they held my nose, it would help my fertility. It would help me have babies.”

She also had to get used to the toilet customs. “All the women would run after me so we could go together,” she says. “They would hold hands and squat, and we would all have to shit and sing friendship songs together.”

Abramovic and Ulay decided on the Chinese wall “because it’s the only human construction visible from space”. She felt her body change along the way. “The wall is a meteorological construction that represents the Milky Way on earth,” she says. “The energy you experience from the wall seemed perfect to us to make a work of art. And it was: it was painful, it was hardship, but it made me merge with the landscape.”

Three months after they had started, the pair finally met, on 27 June 1988, at Erlang Shen, Shenmu, a Buddhist temple in Shaanxi province. “We didn’t want to give up. We wanted to walk the wall, but we knew we had to separate, and that was how our life would be,” Abramovic says. She remembers seeing Ulay for the first time after spending three months walking the wall alone. “First I was angry, then I was sad, then I cried,” she says. Ulay had waited for Abramovic at the temple for three days. “It made me incredibly angry because, conceptually, we were supposed to meet and marry wherever the wall took us,” she says. “I didn’t care about how beautiful the place was. I wanted to be radical with the work. Then he told me his translator was pregnant with his child. He asked me what to do. I told him he should marry her.” They embraced on the wall for the last time. “And then we said goodbye.”

• Shanghai PhotoFairs, Shanghai, China, 20-22 September