The discovery of two unseen watercolours by Paul Signac, painted towards the end of his life, demonstrates his admiration for Van Gogh. As a young man of 25, Signac had passed through Provence and visited Van Gogh in the hospital in Arles, after the Dutchman had mutilated his ear. Together they spent the day discussing painting, literature and socialism, and in the evening they paid a visit to the Yellow House, to see Van Gogh’s recent canvasses. “Many are very good and all of them very intriguing”, Signac commented.

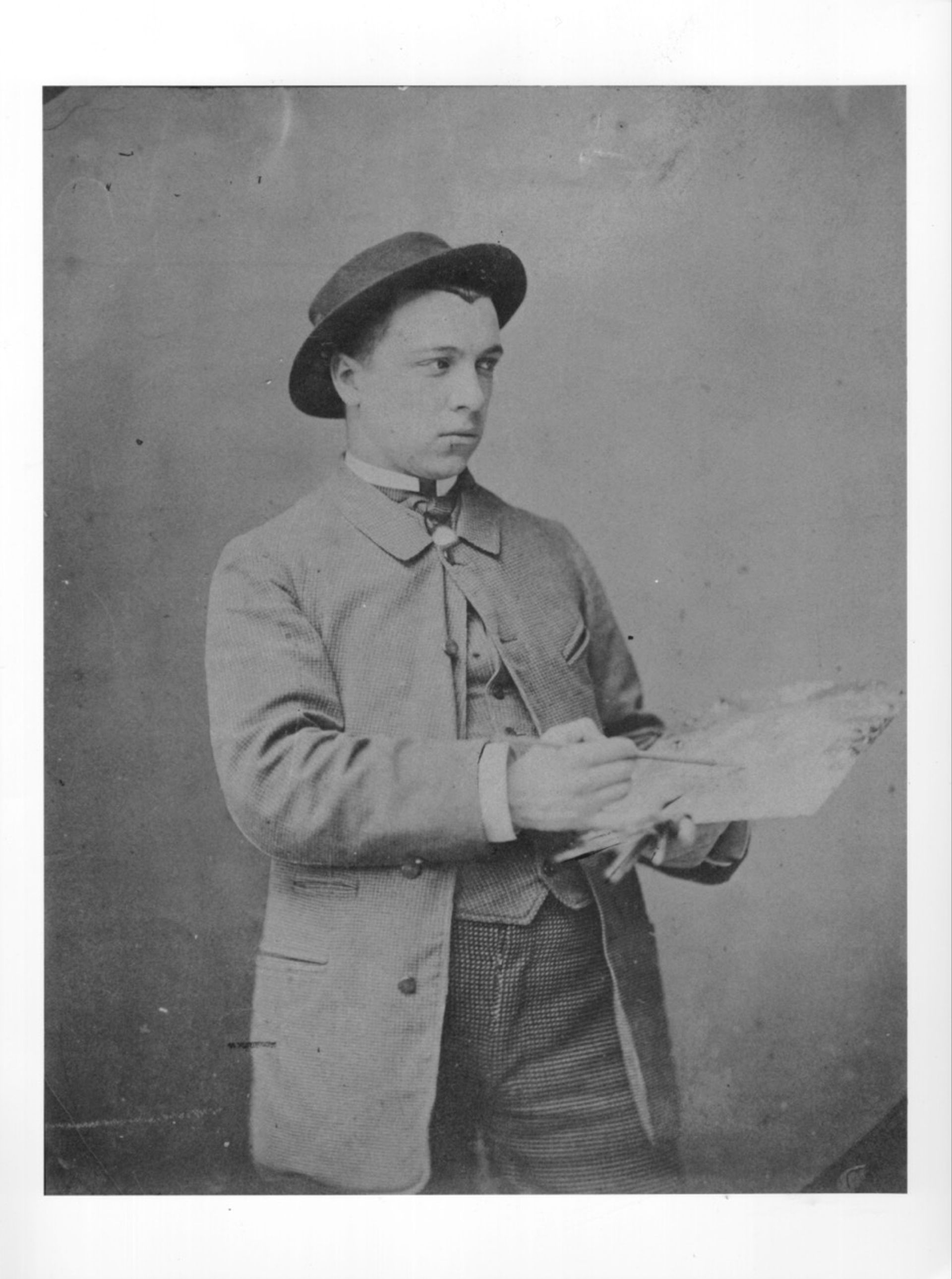

Paul Signac, photograph aged about 18 (about 1881) © Archives Signac, Paris

Just under a year later Signac was in Brussels for an exhibition of the group Les Vingt, where Van Gogh was represented with six paintings, including two of his Sunflowers. At the opening banquet, a row broke out, with the established Belgian artist Henry de Groux demanding that Van Gogh’s paintings should be removed. De Groux provocatively proclaimed his insistence: “not wishing, as far as I am concerned, to find myself in the same room as the unspeakable pot of sunflowers by Mr Vincent, or by any other agent provocateur”.

Octave Maus, the secretary of Les Vingt, later recalled: “Lautrec jumped up, arms in the air, shouting that it was scandalous to slander such an artist. De Groux retorted. Tumult. Seconds were appointed. Signac declared coldly that if Lautrec were killed he would take up the affair himself.” Toulouse-Lautrec, with his short, stunted legs, might have made a weak dueller, so the young Signac nailed his artistic colours to the mast. De Groux then resigned from the group, so the threatened duel never took place.

I was astonished to discover that thanks to Signac, the president of France—no less—must have seen the paintings of Van Gogh, an artist who could hardly sell his work. Two months after the Brussels show Van Gogh presented his work at the Indépendants exhibition in Paris. Sadi Carnot, the president, was escorted around by Signac and spent over an hour there. Van Gogh’s ten paintings must have come into view and his friend Signac is very likely to have pointed them out.

According to an 1890 newspaper report, Carnot was struck by the “disconcerting tonalities” of some of the paintings in the exhibition, leaving “rather amazed”. The president of France can hardly have missed the Van Goghs.

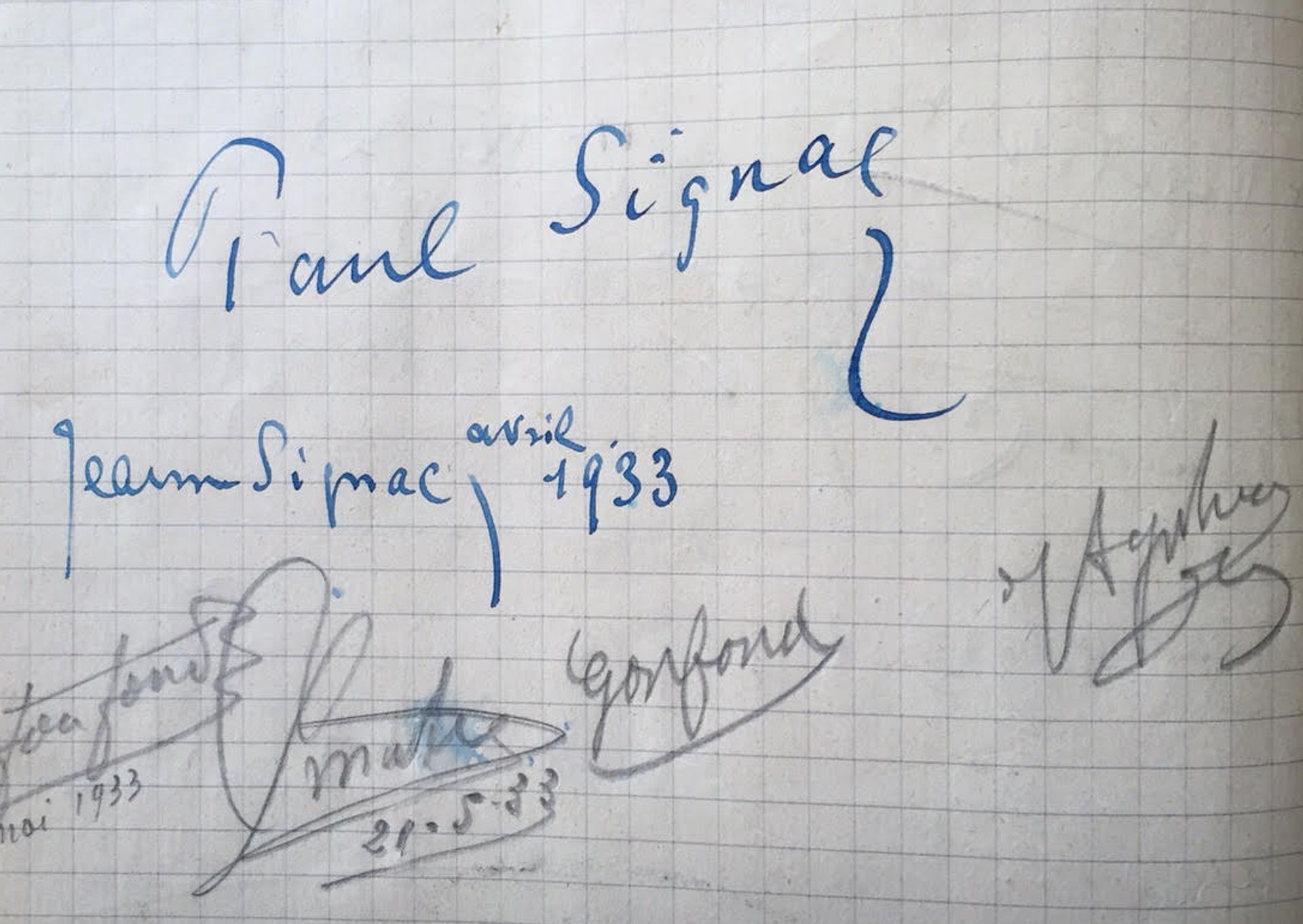

Visitors’ book for the museum at Saint-Paul-de-Mausole, signed by Paul Signac, April 1933 © Archives Municipales, Saint-Rémy-de-Provence. Photograph by Martin Bailey, reproduced in Starry Night: Van Gogh at the Asylum, p. 176

Over 30 years later Signac returned to Van Gogh’s Provence. I recently found Signac’s distinctive signature, dated April 1933, in the unpublished visitors’ book for the small museum which had been opened at the asylum where Van Gogh had stayed in 1889-90, on the outskirts of Saint-Rémy-de-Provence.

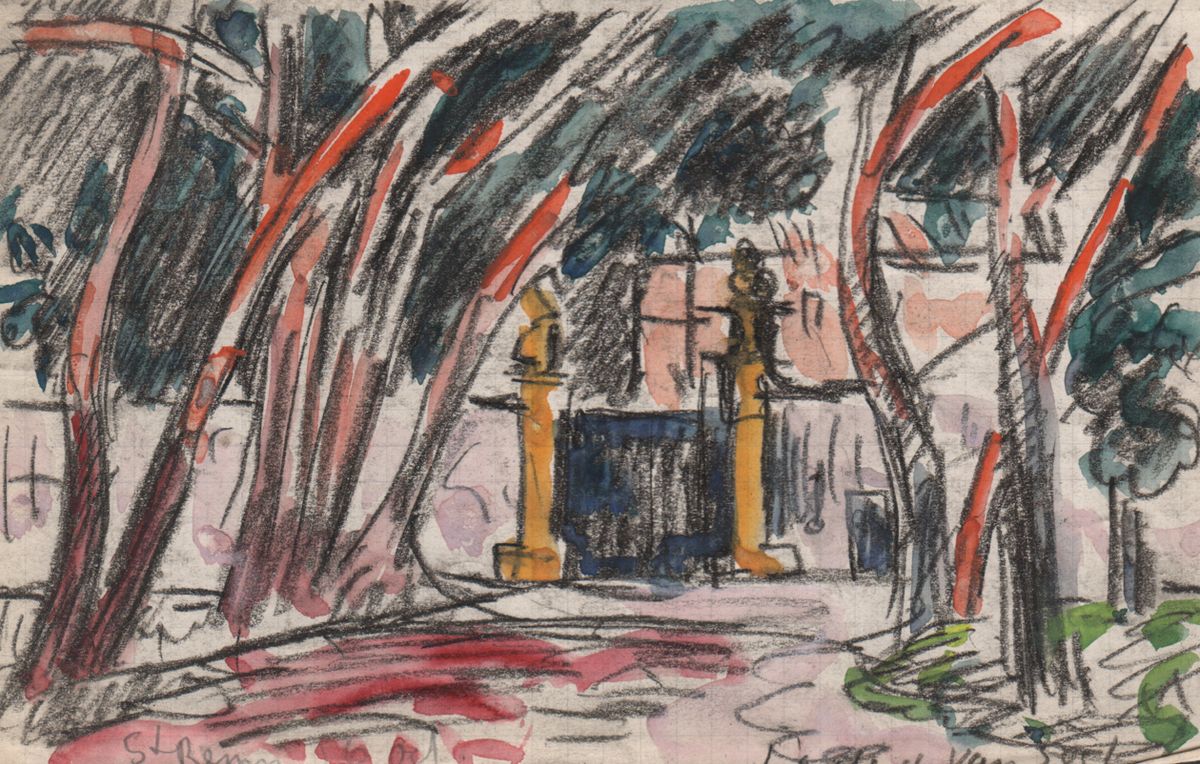

Paul Signac's St-Rémy, L’asile de Van Gogh (1933), watercolour, 17 x 11 cm © Archives Signac, Paris

More recently, Sjraar van Heugten, the curator of the coming Van Gogh exhibition at the Noordbrabants Museum in Den Bosch, contacted the Signac Archive, maintained by the artist’s descendants in Paris. Charlotte Hellman-Cachin, a great-granddaughter of Signac, later identified two watercolours of the asylum in a sketchbook. These are reproduced here for the first time and the horizontal one will be published in the Noordbrabants catalogue (two already-known Signac watercolours of the Yellow House in Arles will be in the exhibition).

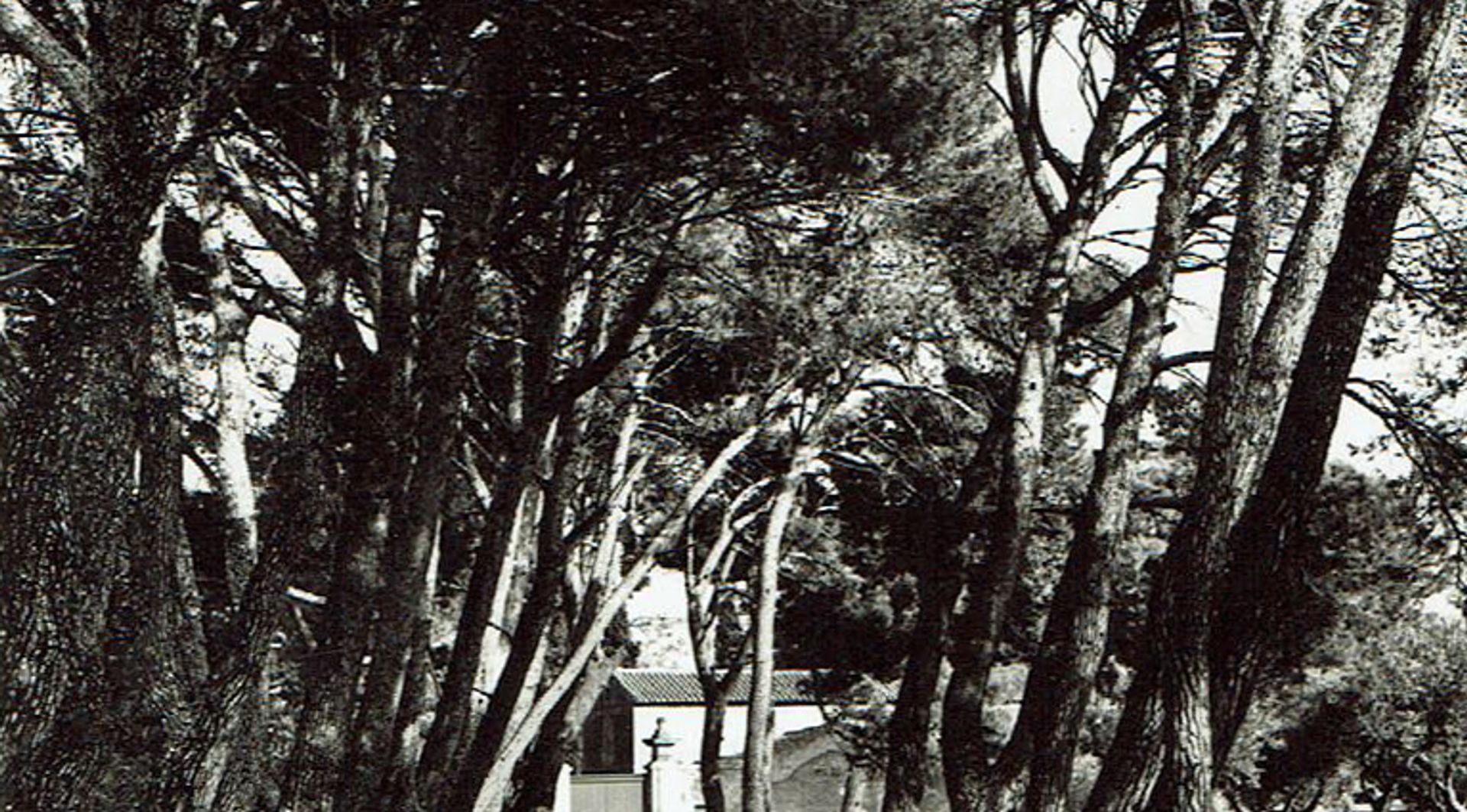

View from the Avenue of Pines towards the entrance gate of Saint-Paul-de-Mausole, around 1950

The two watercolour sketches depict the view towards the asylum from the Avenue of Pines, which leads from the main road to Saint-Paul-de-Mausole (now a modern psychiatric hospital). The institution is surrounded by high walls and Signac has depicted the gates firmly shut, flanked by their imposing columns. In the vertical watercolour, the triangular roof of the Romanesque monastic church can be seen.

Signac died two years later in 1935, aged 71. His newly discovered watercolours represent an homage to Van Gogh.

• Van Gogh’s Inner Circle: Friends, Family, Models, Noordbrabants Museum, 's-Hertogenbosch (Den Bosch), 21 September-12 January 2020