Conifera, an installation made from 3D-printed bioplastic bricks, by COS × Mamou Mani. Shown at Salone del Mobile, Milan © Image courtesy of COS

During this month’s London Design Festival (14-22 September), visitors to the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) will be greeted by a vast illuminated box suspended in the entrance hall. This minimalist “chandelier” will in fact contain a screen and timeline, massively amplified by the box’s mirrored lining, detailing plastic’s takeover of the world’s oceans. “In 1900, around when plastic is invented, the oceans’ content is mostly marine life, and by 2050, it will be half marine life, half plastic,” says its author, the London-based architect and curator Sam Jacob.

The scale of the piece, and that viewers stand beneath it looking up and feeling overwhelmed, are ways of making us think, Jacob says. “The amount of information we have is now so huge, it’s hard to handle,” he continues. “It’s more important to provoke a visceral reaction first, and to visualise data in some way. Making something visual makes it more powerful.”

He is far from alone in this objective. As everything from connectivity to the awareness of climate change gathers speed, many designers and artists are aiming to drive emotional responses first, in the hope that intellectual enquiry will follow. In this year’s dazzling Milan Triennial, called Broken Nature, Paola Antonelli, the senior curator of architecture and design at New York’s Museum of Modern Art (where parts of the exhibition will travel to next spring), proposed ways for humankind to design a more dignified exit from this planet. “Our extinction is inevitable,” she says, “but we can postpone it a bit and make it better. What’s broken cannot go back, but it can go forward into something new.”

Antonelli’s prompts included a huge-scale opening work, The Room of Change (2019)—an assessment of the relationship between human and nature, from ancient times to now. Here, data is not just shown in a conventional way, but also through intricate glyphs woven into a handmade 30m-long tapestry created by the data visualisation experts Accurat. The show also included Bernie Krause’s The Great Animal Orchestra (2016)—an absorbing, immersive piece that not only reveals the exquisite orchestration of animals in the wild, but also the huge reduction in their numbers due to human intervention. “In a big exhibition, you really modulate the way people move through. It’s a storyboard in your mind,” Antonelli says. “We began with large-scale Nasa images and The Room of Change, and then moved to daily life with the Menstruation Machine (2010), a device that allows men to experience the pain of monthly bleeding. The Great Animal Orchestra allowed a moment of reflection and meditation to be carried away.”

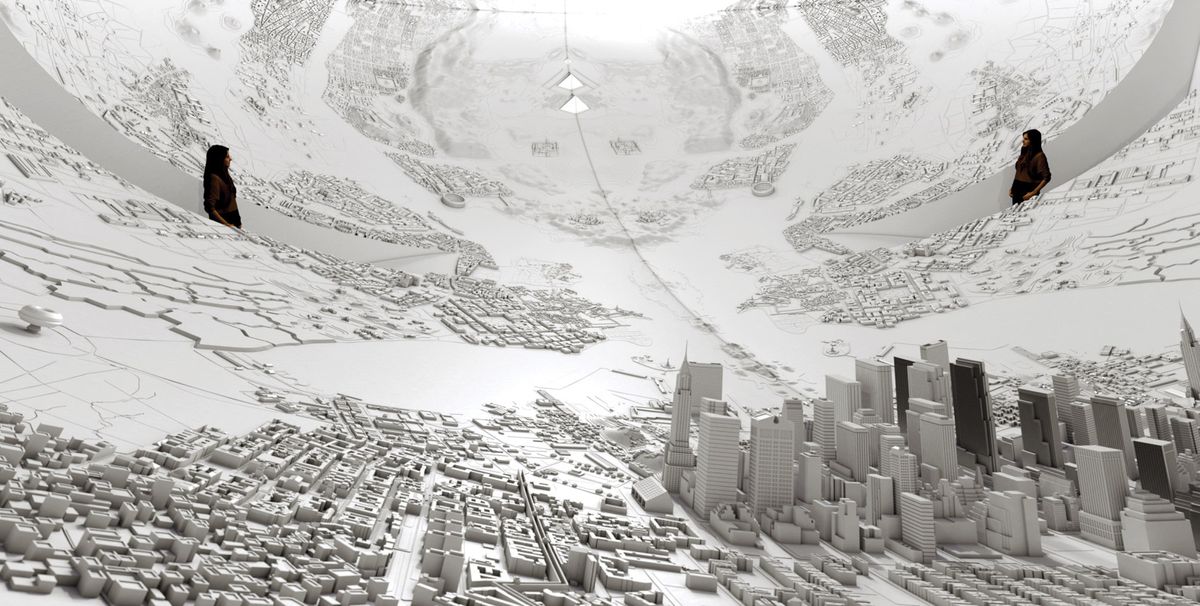

Es Devlin’s Memory Palace (2019) offers a vast chronological landscape of human development, from South African cave drawings to the steps of the Swedish parliament, where Greta Thunberg launched her climate change campaign Courtesy of Es Devlin

At Pitzhanger Manor in west London this month, a new work called Memory Palace (2019) by the designer Es Devlin promises a different path to enlightenment. Devlin is a theatre and opera designer who has also created extraordinary shows for the world’s biggest pop stars including Beyonce and U2. In 2016, she moved into making environmental works with Mirror Maze (2016), an elaborate installation of mirrored walls and bursts of scent in a South London warehouse, which aimed to envelop visitors in the power of perfume. (The work was commissioned by Chanel.)

In her new piece, commissioned by Pitzhanger, she has been influenced by the theorist Timothy Morton’s assertion that artists and designers are key players in nudging people out of their established ways of thinking—in particular, facing up to our ecological responsibilities. “Morton’s invitation to designers and makers is for us to amaze people into changing their minds,” Devlin says. “To visualise, to hallucinate, to see around the corners.”

Devlin’s vast sculptural work, carved from bamboo, will slot inside the Pitzhanger’s gallery space to create an ovoid room. Inside, visitors will be surrounded by Devlin’s imaginary cityscape, a jigsaw of real locations that signify sites of major societal shift. “In the studio, we researched a timeline of events, from the first time a human drew on the wall, in the Blombos caves in South Africa 73,000 years ago, to the first time we had enough organised labour to build the pyramids, to the room where Confucius wrote the laws of reciprocity, to the trenches of the First World War, to the steps of the Riksdagshuset where Greta Thunberg began her student climate change action,” Devlin says. “It is entirely subjective, but I hope by showing these shifts in perspective, there will also be a consoling effect, that we can bring about change. We have abolished slavery, we have enabled women’s liberation. Now we can tackle climate change and adopt and develop new thinking.”

Devlin is keen for people to enter the space on their own and to take their time. “They’ll walk into a white ovoid expanse, so there is an initial, material, phenomenological experience,” she says. “Some will just enjoy being in what is a kind of model city. But I hope people will question what we’ve done and why.”

Doug Aitken’s New Horizon (2019) travelled across rural Massachusetts in July to highlight issues of conservation Courtesy of Doug Aitken Workshop and The Trustees

At Victoria Miro’s London gallery, the Los Angeles artist Doug Aitken, is busy preparing an exhibition that will consume both the inside and outside space that the Wharf Road building offers. “We’re moving into a new chapter,” Aitken says, “with a rate of information and connectivity that’s hard to handle. The counterpoint is the return to the real, the physical, the ambient.” Aitken is known for his large-scale works that play with perception like New Horizon (2019), a semi-mirrored hot air balloon that flew over rural Massachusetts in July as part of a commission by Trustees, a local non-profit preservation and conservation organisation. His London installation will offer a world of ever changing light, colour and reflection, from contemplative to intense and febrile—what he describes as “sensory and proactive”, where the viewers are also participants in the work.

Indeed, the viewer is frequently in a proactive position now. The idea of going to a gallery to stare at a wall long ago ceased to be the standard mode of receptivity. Studio Swine, a British/Japanese design/art duo based in Brooklyn, met at the Royal College of Art in London where they developed unlikely ways of making eyewear out of human hair. Gradually, they have shifted their practice from the object to the experience. “We like things that disappear into the air,” they say. “At some point, we realised—like everyone—that the world was too full of things and that it is more interesting to effect people’s behaviour and thinking, and that people place great value on experiences and memories and a sense of involvement.” A few years ago, they developed an installation called New Spring (under the auspices of the fashion label Cos), which was shown in Miami and Milan. It was an artificial tree, made of metal, that dispensed scent-filled bubbles. “Scent short-cuts or bypasses language; it will evoke feelings before you have time to register them,” they say.

“My work isn’t on a pedestal, it’s something you might cycle past every day, it’s the opposite of instantaneous. It could gradually become part of your life. It could most definitely make you think.”

Studio Swine are currently working on a speculative water tower—something they hope will be commissioned—on the grounds that no further public sculpture should be made unless it also contributes to the environment, in this case as a water-collecting receptacle. “We see that as the future,” they say.

Back in London, the designer Simon Heijdens, who has always eschewed the realm of objects, is currently working on two institutional works for the Netherlands. Heidjens typically works with light and nature, writing algorithms that allow environmental actualities from wind and rain or people passing by to make light patterns grow on the exterior walls of buildings. Heidjens studied design and experimental film-making, “but I never felt happy about making people sit and watch a screen,” he says. “I’ve always been drawn to something more spatial and 3D.” His objective is “to soften the environment”, he says, while making us engage with the presence and importance of the natural world, even in the man-made city.

“My work isn’t on a pedestal, it’s something you might cycle past every day, it’s the opposite of instantaneous. It could gradually become part of your life. It could most definitely make you think.”

• London Design Festival, 14-22 September; Memory Palace by Es Devlin, Pitzhanger Manor, London, 26 September-12 January 2020; Doug Aitken, Victoria Miro, London, 2 October-20 December; Broken Nature—Triennale di Milano, 1 March-1 September

• Read more articles from our special Art & Design supplement in the September issue or online here.