The Hungarian avant-garde artist Dóra Maurer, who was recently catapulted into the spotlight with a year-long display at Tate Modern, says “a lack of market” has been positive for her work, allowing her to experiment without having to produce profitable objects.

Having spent much of her career behind the Iron Curtain, where art was often censored and galleries were driven underground, Maurer made money by working on commissions, as well as designing catalogues and book covers and translating their contents. “I did other work that wasn’t related to my subject matter,” the octogenarian explains.

Now that looks set to change with an exhibition of paintings from the past 30 years at White Cube Bermondsey. It is her second show with the London gallery, which has just announced its representation of her (the artist is also represented by Vintage Galeria in Budapest). White Cube declined to give prices for its show, although, according to sales material seen by The Art Newspaper, works are priced around €150,000.

Maurer’s auction record, meanwhile, stands at a very affordable £8,000 for an atypically representational painting from 1993 of a mill, which sold at Sotheby’s in June 2016.

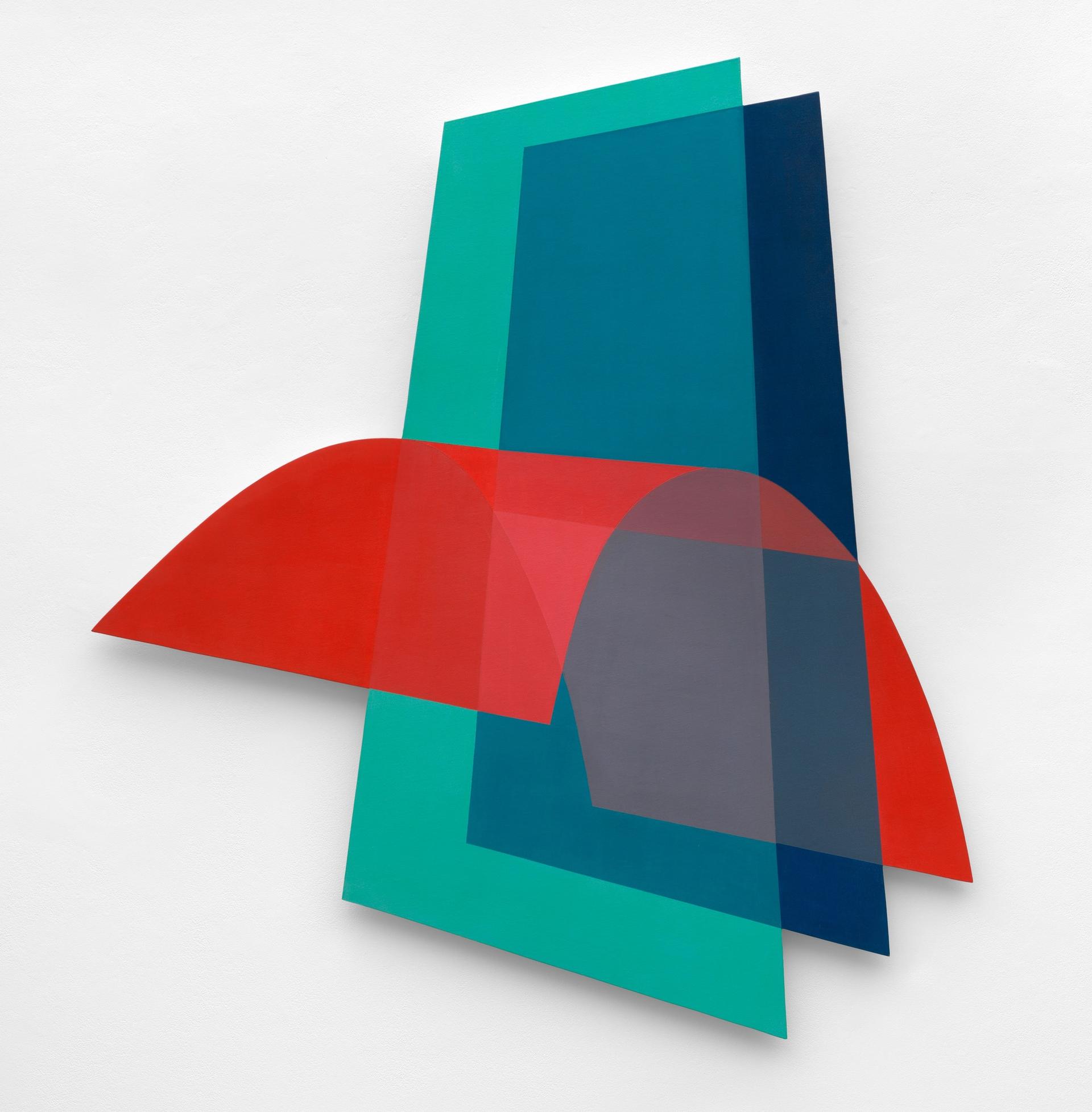

Overlappings 8 (2002) © Dóra Maurer. Photo © White Cube (George Darrell), courtesy White Cube

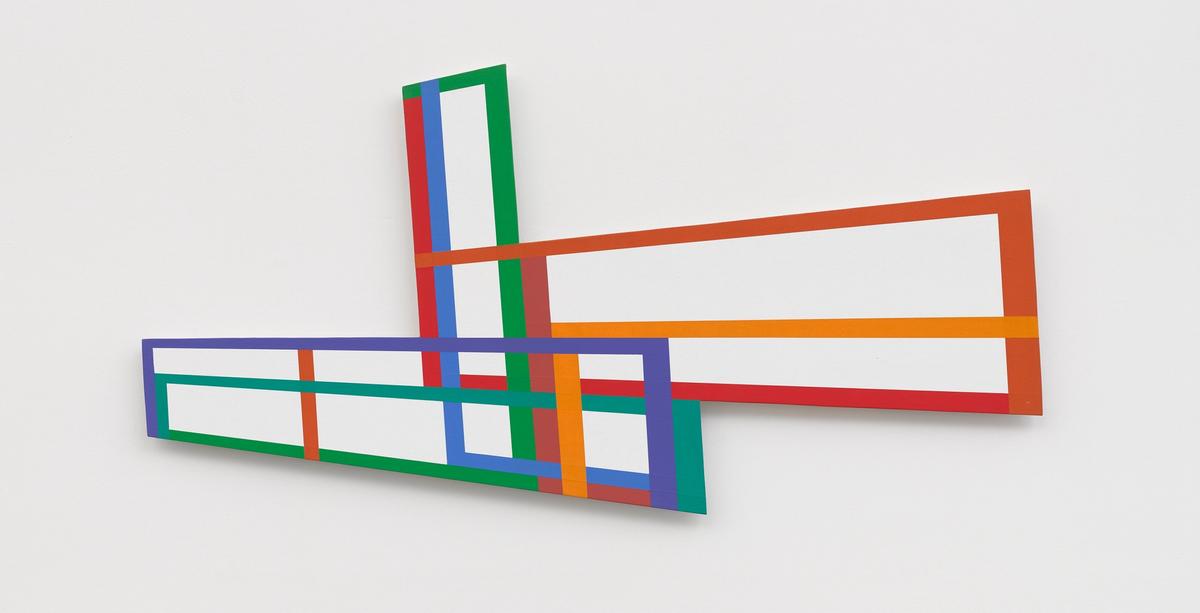

The White Cube exhibition focuses on three series. Overlappings (1999-2015), features works made from slightly curved squares of colours that, as the title suggests, overlap to create other colours (blue and yellow to make green, and so on). Quod Libet (1997-2013), meanwhile, consists of overlaid and interlocked rectangular and square frames in purples, oranges and green. In Maurer’s IXEK (1999-2015), two or three fields of colour intersect to loosely resemble the letter ‘x’.

Colour exploded into Maurer’s work in the early 1980s when she was invited to create a site-specific wall painting and film in a medieval castle near Vienna. “It was interesting to reflect on each colour and see how they interacted together throughout the changing light of the day. I became particularly aware of this when I had to change the colour filter on my camera while shooting the film […] it was a starting point and inspiration for my focus on the perception of colour,” she says.

IXEK 10 (2013) © Dóra Maurer. Photo © White Cube (Todd-White Art Photography), courtesy White Cube

Together with the Tate Modern show, it seems Maurer’s career is in the ascendancy, although she is ambivalent. “The spotlight is good, and not,” she says. “Lots of interviews are done. I feel like [I’m] in a vacuum; there is no resistance and there is no effect on my job. I [am] not a star: I need calmness and time as well.”

It is a familiar story among female artists, many of whom are only now getting their dues. White Cube is showing two other women in its Bermondsey gallery at the same time as Maurer. They are Mona Hatoum, the Palestinian-British, long-time White Cube artist and former YBA, and the US artist, curator, author and activist Harmony Hammond, for whom it will be her first exhibition in Europe. All three exhibitions run from 12 September to 3 November.

Maurer says her gender has never put her at any real disadvantage: “I was immediately accepted by both constructive artists and experimental film-makers.”

Here in Hungary I have never met anyone who would have downplayed my work because I am a woman

She adds: “I have never considered drawing or painting [nor do I still see it] as gender-specific, and here in Hungary I have never met anyone who would have downplayed my work because I am a woman. On the contrary, there was a scholarly acquaintance who saw both female and male principles in my work.”

She has encountered a few “primitive manifestations” outside of her native Hungary, however. “In Germany, there were several rejections,” she recalls. “Interestingly, I heard a macho expression, not from a civilian but from a renowned art historian, museum director, who was not even aware of how macho he was. One of them flipped through my husband Tibor [Gayor’s] work in a folder, then opened my folder and exclaimed, ‘Ah! The woman also makes art!’”

Experimentation remains at the forefront of Maurer’s practice. There were plans for her first film—“a combination of surround-sound recording and musicians’ facial details”—but a lack of money and technology meant the project was never realised.

Perhaps now that White Cube has picked her up, there will be the resources for her to bring such ideas to fruition. Currently, she says she is “interested in combining music and shaped canvas paintings”. But she rues those early experimental days. “I have to confess that in the 1970s, techniques were more accessible, one felt great freedom and solidarity,” she says. “The lack of this makes many things impossible today.”