Two years ago, Theaster Gates saw his first permanent outdoor commission, Black Vessel for a Saint, installed in the Minneapolis Sculpture Garden under the stewardship of the Walker Art Center. A cylindrical temple-like structure made of bricks, it housed a salvaged statue of Saint Laurence, reflecting the artist’s passion for reclaiming abandoned objects in his native Chicago.

Now Gates is building on his relationship with the Walker in an invocative solo exhibition opening there on 5 September. Titled Theaster Gates; Assembly Hall, it draws on the artist’s vast collections of cast-off objects on Chicago’s South Side to create four grippingly immersive environments. The goal is to present a Gesamtkunstwerk, or total work of art, celebrating Gates’s capacity for investing forgotten things with fresh poetic meaning.

Theaster Gates's Black Vessel for a Saint (2017) in the Minneapolis Sculpture Garden Gene Pittman, courtesy of Walker Art Center

“We wanted to create a unique experience of his practice,” Victoria Sung, an assistant curator of visual arts at the Walker who organised the exhibition, said in an interview. “The four environments highlight not just his own art-making but his collecting, making the argument that his collecting is in and of itself an artistic gesture.”

Or, as Gates said in an email, “The show is not about my work but rather, how history and especially other people's historical objects inform how I work.”

To brainstorm about the exhibition, Sung says, she flew to Chicago several times to walk with the artist through Dorchester Projects and the Stony Island Arts Bank, formerly abandoned buildings on the city’s South Side that Gates now uses for cultural gatherings and for showcasing his collecting. “We would just do laps through his studio,” she says, “and the more we walked around, we found ourselves gravitating toward different collections.”

As a result, the Walker is creating a “clay studio facsimile” that mirrors the studio Gates has at Dorchester and evokes his early beginnings as a potter. Using wood from felled ash trees that the artist has been repurposing in Chicago, the museum is creating floor-to-ceiling shelves displaying Gates’s ceramic wares and building seating where visitors can lounge to take in the experience. Each Thursday, Sung says, the Walker will serve tea to the public in the studio in Gates’s ceramic cups to emphasise “the importance of conviviality” in his art-making.

Ceramic wares created by Theaster Gates Sara Pooley/Courtesy of the artist and Rebuild Foundation

A different room is devoted to “a small subset” of 60,000 glass lantern slides for art and architectural history classes that Gates recouped from the University of Chicago when it was making a transition to digital images, Sung says.

“Theaster said, ‘Don’t throw them away–I can house them on the South Side,” she says. At the Walker, some of the slides will be illuminated in a lightbox display, and Gates has created a moving image in response to them that will be projected on the walls and incorporate a voiceover and music.

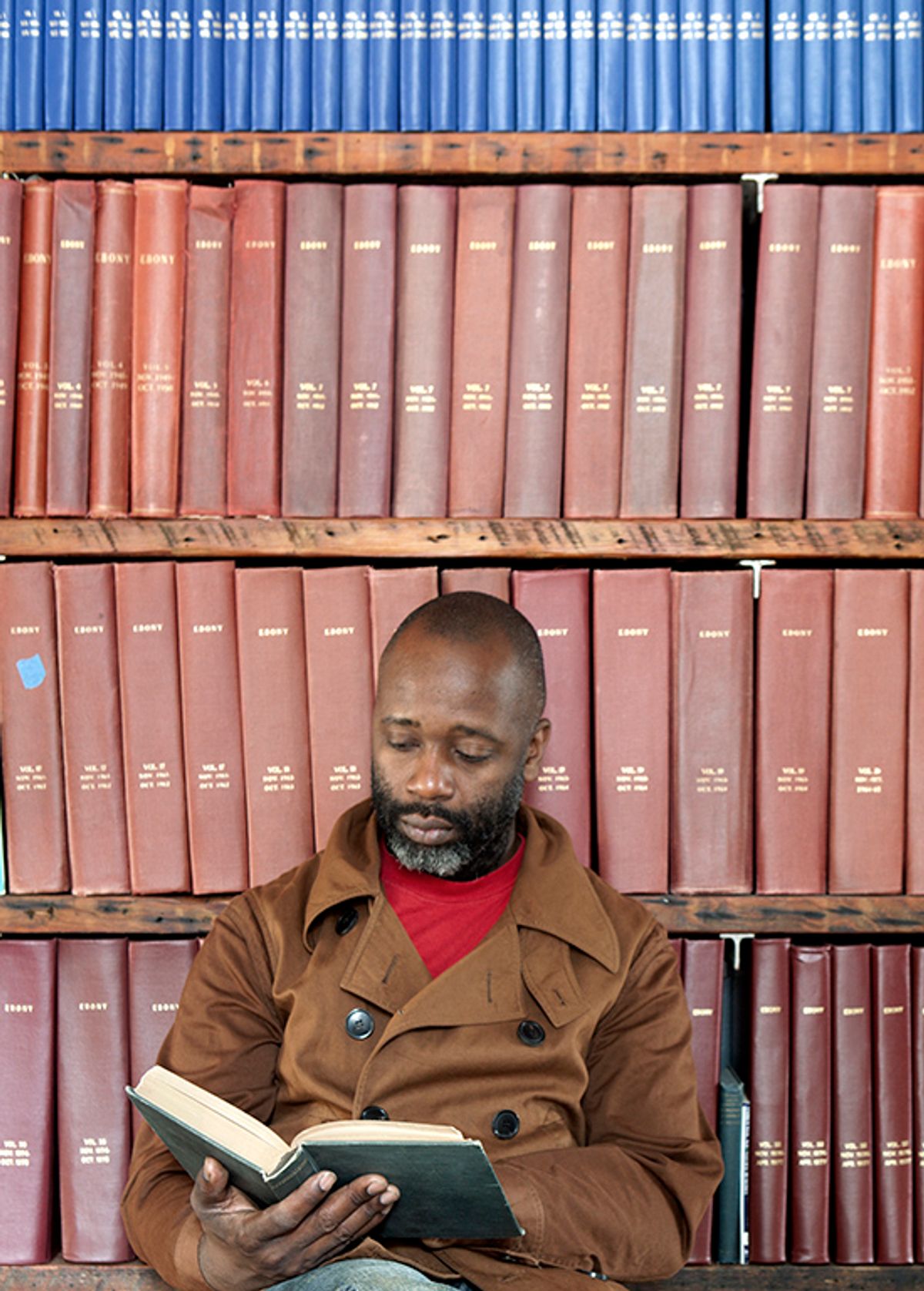

Another room will focus on material retrieved from Johnson Publishing, the Chicago company that distributed Ebony and Jet magazines to an African American public in the postwar era and recently went through bankruptcy proceedings. Gates is conjuring a reading room with magazines and furniture from Johnson’s downtown offices in Chicago, restoring and reimagining some of the pieces with different fabrics and colours. “We’ll really invite visitors to take a seat and read and relax in the space,” Sung says.

Johnson Publishing Company Archives and Collections Courtesy of Rebuild Foundation

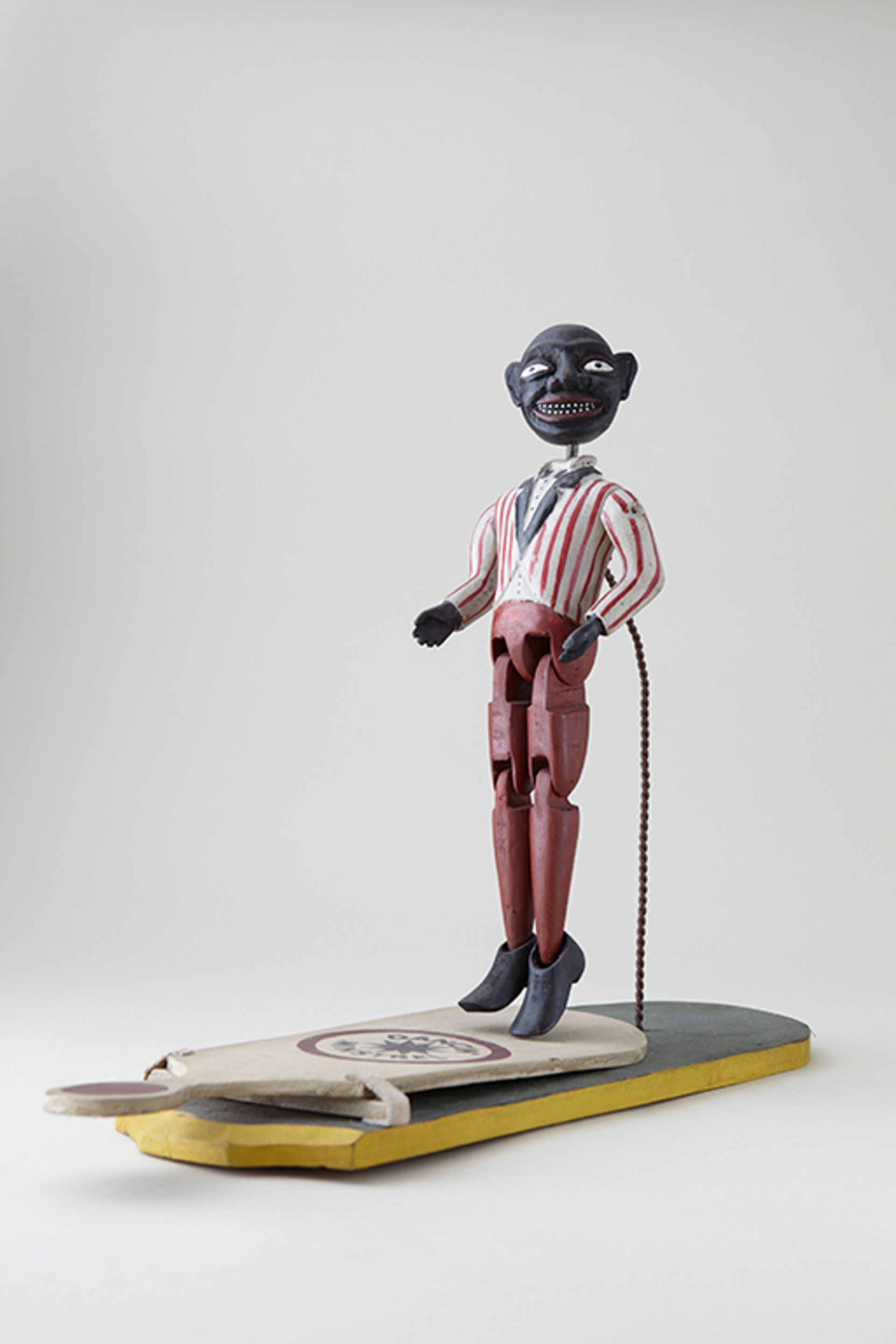

The Walker is devoting another room to items from the Ana J. and Edward J. Williams Collection, comprising thousands of everyday consumer items that feature racist stereotypes. Initially Edward Williams collected the objects to “get them out of circulation”, Sung notes, but he eventually realised that “this was a part of our history that he didn’t want people to forget”.

In that spirit, Gates is presenting a configuration of objects from that collection–kitchen items, toys, advertising–in traditional vitrines in a space that “feels like an old anthropological vault in an ethnographic museum”, Sung says. The goal is to highlight the role that art museums and other institutions have played in creating skewed narratives about different cultures.

Dancin’ Minstrel With Tap Board from the Ana J. and Edward J. Williams Collection Courtesy of Rebuild Foundation

The Williams Collection features “a range of really damaging and dehumanising caricatures that, because of their form as everyday objects of consumption”–an Aunt Jemima syrup bottle, for example–“we may not realise that they had a racist origin,” the curator says.

Sung is eager to witness how visitors will respond to each immersive environment as the objects are introduced in a museum context.

What Gates is aiming for is “a kind of resurrection”, she says. “We really hope that people will walk away with a deeper appreciation of these histories of African American culture.”

Or, as the artist put it, “I am excited that there are moments in the exhibition when the visual literacy of blackness erupts into new reflections on what and how we see.”

• Theaster Gates: Assembly Hall, Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, 5 September-12 January 2020