Last week, it was announced that four foundations—the J. Paul Getty Trust, the Ford Foundation, the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation and the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation—had teamed up to buy the photography archive of Johnson Publishing, the Chicago-based company behind Ebony and Jet magazines, for $30m. Comprising more than four million photographs and 10,000 hours of video, the collection spans eight decades of images of black American life, portraying leading entertainers, athletes and politicians as well as pivotal moments in black history.

Johnson had filed for protection in Chapter Seven bankruptcy proceedings, and some had feared that the images would be snapped up by a private collector at the resulting auction and become unavailable to the public. The foundations prevailed: they plan to preserve, catalogue and digitise the photos and video for perusal online, and donate portions to the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of African American History of Culture in Washington, DC, the Getty Research Institute in Los Angeles and other cultural institutions.

The Art Newspaper interviewed George C. Fatheree III of the law firm Munger, Tolles and Olson, the lead counsel to the J. Paul Getty Trust, about the acquisition.

The Art Newspaper: I see that this deal came together in a hurry. How did it all get started? Have the foundations ever cooperated on a bid in the past?

George C. Fatheree III: This is the first time these foundations have come together to do something like this. In fact, this type of partnership, especially given the timing, is unprecedented in the foundation community—it speaks to the importance and uniqueness of the archive and this opportunity. It also speaks to the commendable collective commitment by the Getty Trust and the Ford, MacArthur and Mellon foundations to preserving this historically and culturally invaluable documentation of the black American experience.

Lena Horne with her Siamese kitten, Anna, in an undated photo. Isaac Sutton/Johnson Publishing Company)

A couple of the foundations had been discussing the possibility of acquiring the Johnson Publishing Company archive previously, but those conversations did not result in participation in the initial auction. My firm, Munger, Tolles and Olson, got the call from the Getty two days before the auction was set to resume. The Getty was interested in acquiring the collection and wanted advice around how to participate in the bankruptcy auction. We reached out to the bankruptcy trustee and banker who were coordinating the auction and explained that the Getty was interested in participating, but that we’d need to postpone the auction for two weeks so that we could get up to speed, complete diligence, negotiate a purchase agreement and coordinate our bid with the other foundations. The bankruptcy trustee agreed to delay the auction for two days. We got to work immediately.

What made this archive so important to them?

The archive is singular in its size, scope and subject matter—nothing like it exists. It poignantly and beautifully captures—in approximately four million images—the black American experience over the past eight decades. These images and stories have largely been omitted from mainstream media and institutions, but by acquiring the archive, the foundations will help ensure that these images and the stories they represent will be preserved in perpetuity as an integral part of our history and experience.

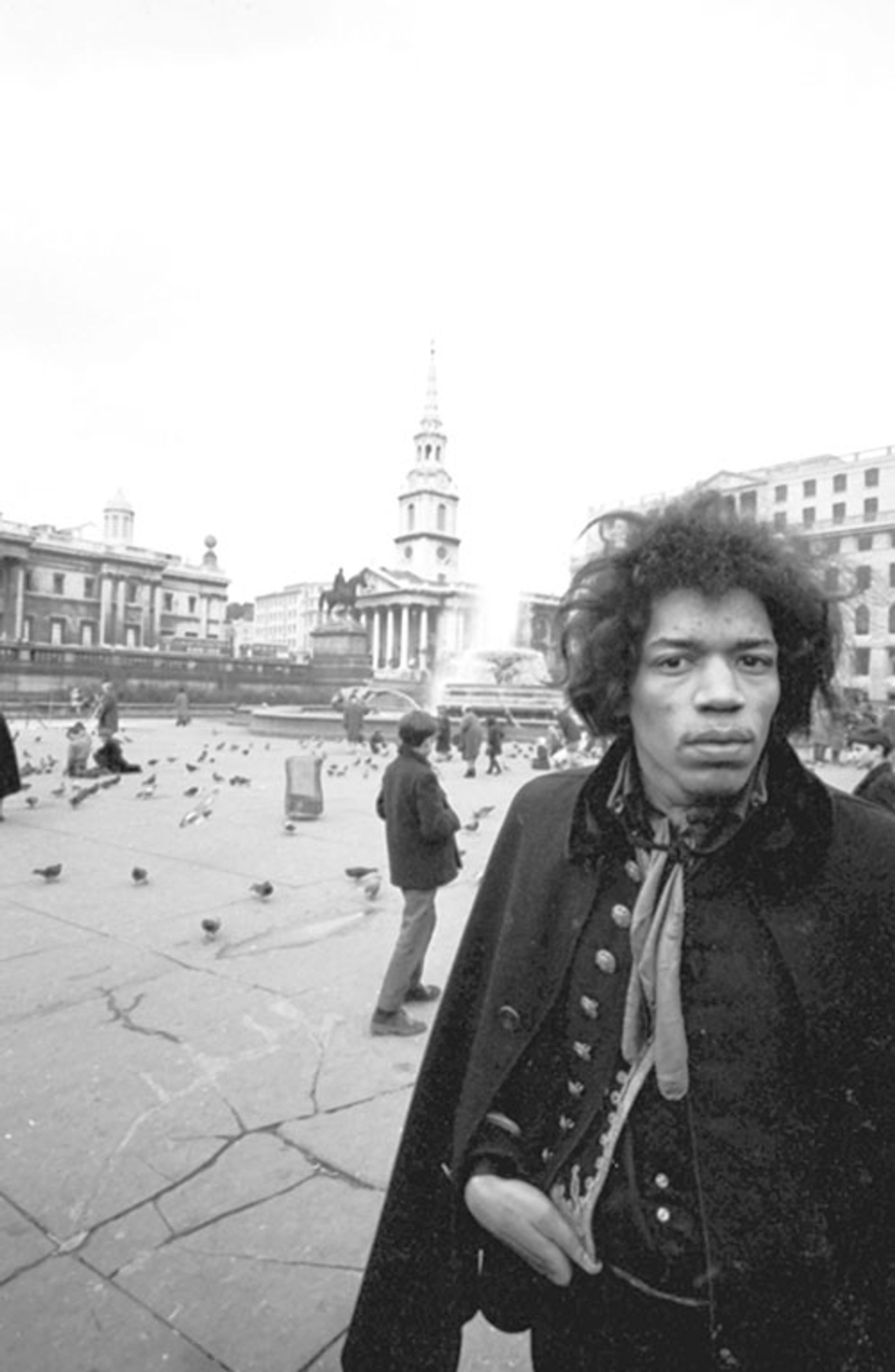

Jimi Hendrix in London in 1968 Charles Sanders/Johnson Publishing Company

Describe the range of the photographs. Are most of them of black celebrities?

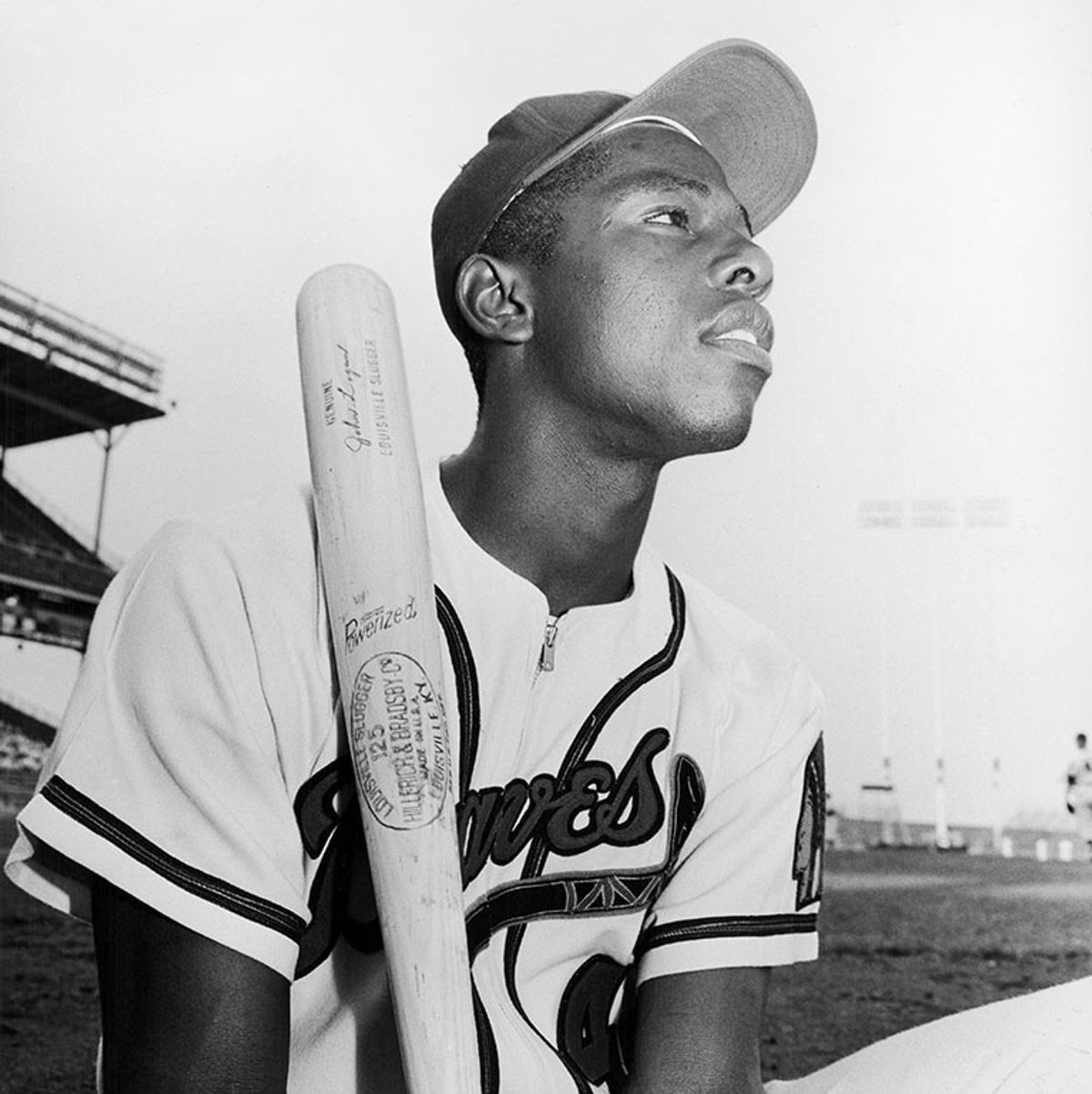

The photographs span eight decades—they capture not only people and places, but also visually depict feelings and moods. Viewing the photographs, what strikes you is how beautifully shot they are—how perfectly they capture emotion: strength, grace, struggle, triumph, perseverance. There’s something about the black-and-white images that bestows a sense of authority and importance. They depict civil rights leaders, musicians, politicians, religious figures, athletes, actors—they document our heroes. The photographs also show everyday people taking the bus to work, standing in line, marching in a protest, singing in church. What comes through is the dignity and conviction of the people, their certainty of purpose.

For you, are there any particular standouts?

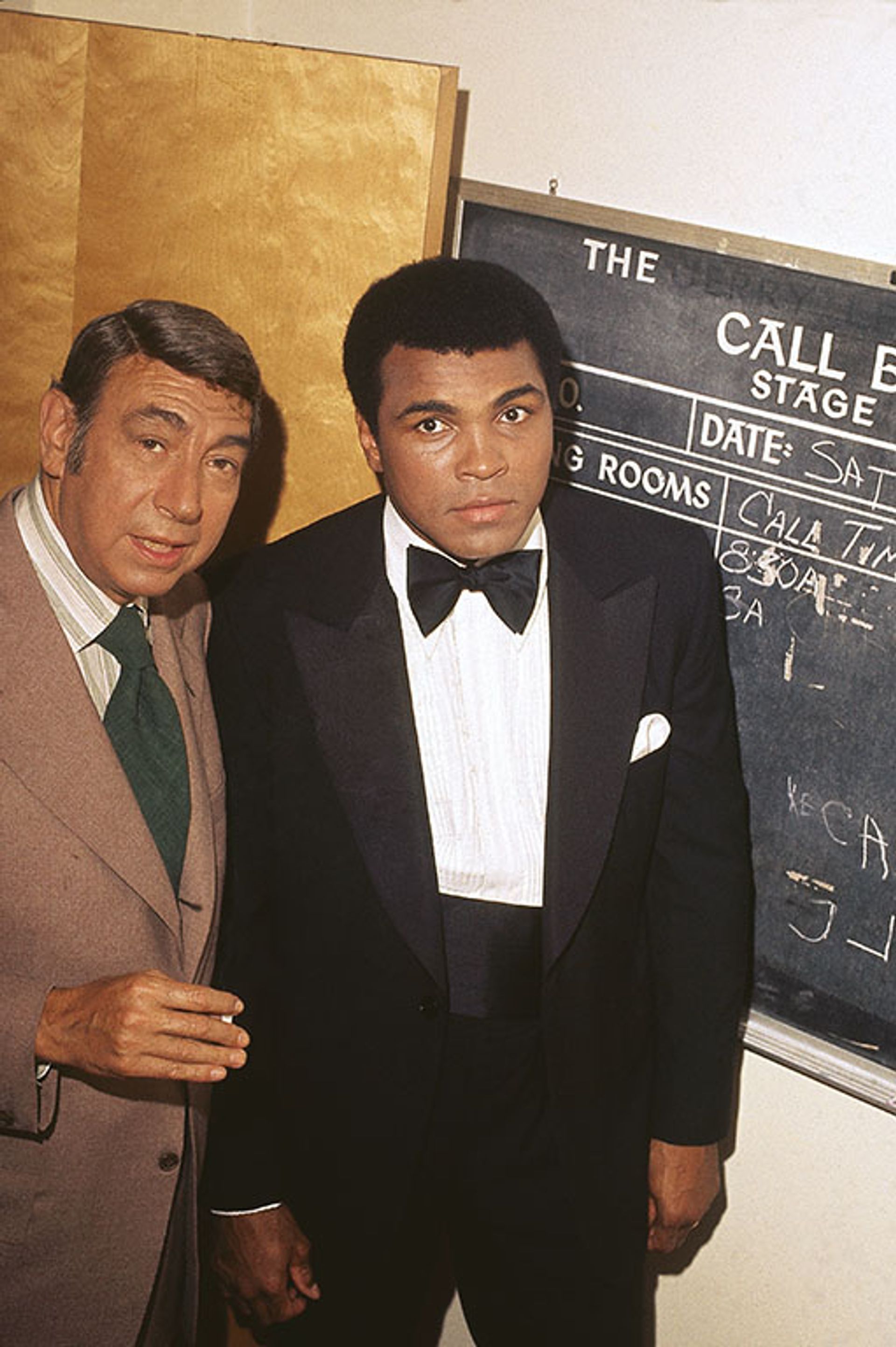

The photographs document the historic public moments we are familiar with—Jimi Hendrix onstage, Miles Davis in the studio, Malcolm X at a rally, Muhammed Ali delivering a devastating blow. But they also capture more private moments—Dorothy Dandridge in her home with her dance instructor, Ray Charles playing dominoes, James Baldwin leaving his apartment. These images increase our familiarity and create an intimacy with our heroes and role models.

Muhammad Ali backstage with the sports journalist Howard Cosell before a television special in 1975 Isaac Sutton/Johnson Publishing Company

Probably the thing that surprised me most is that the archive included photographs that were sent to the magazines of black men who had been beaten, shot and killed by the police. These photographs were sent to the magazines to be published to awaken the country and world to the inhumane and unjust treatment black people experienced at the hands of US law enforcement. Many of the photos included a handwritten description on the back describing who the victim was, and what the police had done to him.

These images were absolutely devastating. The photographs I saw were from the 1960s, but the shameful realisation I had was that they could have been taken yesterday. This remains a stain on our national consciousness that we’ve been unable to scrub out. I hope that these images from the archive will serve as a type of mirror and force us to finally confront and eradicate these despicable practices.

Coretta Scott King in an undated photo

What impact do you see Ebony and Jet as having on their respective audiences in their heyday?

I think that Ebony and Jet were beacons to black people. They showed our faces, told our stories, shared our voices. So often we look to media for our impressions of what is beautiful and what has value, but for much of our history, black people and their experiences had been systematically excluded from these affirmations. Jet and Ebony changed that—they portrayed black faces, told black stories and in doing so affirmed black beauty and value.

The magazines played a larger role as well—they were ambassadors of black people and life to broader America. Much in the way that The Cosby Show (which I know is taboo to say now) introduced black people into white households, I think Jet and Ebony played a similar and crucial role.

Mary Wilson, Diana Ross and Florence Ballard of the Supremes while on tour in Europe in an undated photo G. Marshall Wilson/Johnson Publishing Company

Have any of the photos been digitised? Where are they for now?

The photographs currently remain stored in Chicago, but the intent is to transfer them to the Getty Research Institute in Los Angeles and to the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, DC. The Getty intends to catalogue and digitise the archive to ensure that it is preserved in perpetuity for academic and scholarly purposes and made available online for the public to experience and enjoy.

Were there any challenges with the transaction?

This is one of the most challenging transactions I’ve ever worked on.

The actor and comedian Redd Foxx in front of his hair styling salon in an undated photo Isaac Sutton/Johnson Publishing Company

You start with the timing. We basically had two days to get up to speed with the bankruptcy proceeding, put our bid together, conduct due diligence, negotiate a purchase agreement and finalise an MOU [memorandum of understanding] among the four purchasing foundations. After we won the auction, we had two additional days to deal with any objecting parties, negotiate the court’s sale order, finalise closing documents and tee up the funds.

Next, you take the size and the scope of the archive, its approximately four million images. We had to be smart and creative about how we performed our diligence and what questions we asked. There were numerous parties involved: the four foundations, the bankruptcy trustee, the seller and various other parties had potential claims to the photographs in the archive. This transaction also presented a complex mix of legal issues, including bankruptcy, art law, partnership, intellectual property, real estate, employment and personal property ownership.

The fact that we were able to get this deal done is a testament to the four foundations, which were unwavering in their commitment to acquire and preserve this important archive. It was also due in great part to the commitment, resources and experience of my firm, Munger, Tolles and Olson. Our attorneys dropped everything to pitch in and lend their skills and expertise to ensure that we focused on the key issues and had a successful closing.