For as long as there has been art there has been the destruction of art. If creating objects can be seen an act of asserting one's culture, then destroying or modifying them is a powerful gesture of dominance—a bold declaration of a new leader, ideology or era. The exhibition What Remains (until 5 January 2020) at the Imperial War Museum (IWM) in London is exploring this topic over the past century, including Nazi Germany's targeted bombings of British tourist sites and the Taliban’s destruction of the famous Bamiyan Buddhas in Afghanistan, as well as the ways that heritage is protected and restored.

Organised in partnership with Historic England, the show brings together around 50 photographs, oral histories, documents, artefacts and artworks. One of the contemporary artists in the exhibition is Piers Secunda, whose recent work reflects "the sharp end of geopolitics" by capturing acts of destruction, such as the iconoclastic acts of the Islamic extremist group Isis. Secunda's sculpture-like paintings of Assyrian reliefs include areas of "damage", made from moulds of Isis bullet holes and power tool damage at destroyed sites in Iraq. We spoke to the artist at his London studio about how he makes—and breaks—his own paintings; his new drawings using charcoal from destroyed buildings; and what sites of destruction he wants to work with next.

The Art Newspaper: How did your participation in the show at the IWM come about?

Piers Secunda: Rebecca Newell, the head of art at the IWM, and Iris Veysey, the museum's art curator for contemporary conflict worked together on the exhibition What Remains and they told me that that they wanted to include a section in the exhibition about Mosul. Rebecca had visited an exhibition I was doing at the Iraqi ambassador's private residence, so she and Iris came to the studio and looked at a bunch of works including a drawing I’d made of smashed sculptures from inside the Mosul Museum, which I’d drawn using the charcoal from the burned-out museum itself, as well as paintings of the sculptures with Isis power tool damage in them. Rebecca and Iris decided they wanted a painting for the show that directly relates to Mosul. So I made ISIS Damage Painting (Genie Head) (2019) for them.

An installation view of the Mosul section of the exhibition What Remains (until 5 January 2020) at the Imperial War Museum © IWM

Your paintings are not paintings in a traditional sense. Can you explain the way you create these sculptural-looking works?

I create paintings with poured and set industrial paint. The tradition of painting is the application of paint to a flat surface and it has pre-arranged boundaries in the form of a canvas and so on. For me, that limits too much what painting can be—I want something more organic where I can add and take things away. So I developed many systems of making works of art with paint, where I took the paint for a walk in three dimensions and I tried to figure out how I could enable the paint to grow without those traditional restraints.

What is it that got you interested in the idea of destruction and iconoclasm?

I used to make works out of acrylic and, in 2004, I switched over to this industrial paint because I could pour it and overnight it would be cured completely. This particular material enables me to drill it, cut it, heat it up and tear it, saw it, smash it, paint over it.

When I started to realise that I could really make pretty much whatever I wanted with the new paint, I could then think about engaging with the outside world—I could introduce external elements that would say something about the time that I'm living in. I started trying to find materials from outside the studio, which I could bring into my studio and convert effectively to paint. And the first one that I thought of was crude oil—it is the lifeblood of everything we do all day long. And so I found ways to make crude oil function as a paint.

I then started breaking the surface in a way that I thought would reflect the sharp end of geopolitics. For one of the earliest exercises in that respect, I had the Chinese army shoot at sheets of paint for me to produce the component parts, which would then come together as my paint assemblages. And as a result of doing that, I started to think a little bit more about the violent fracture, which, for me came originally from the Zero Group, and specifically from Lucio Fontana. He was opening the picture plane into the world of three dimensions and sculpture.

For me, it was a matter of further opening up the paint plane via a process that would embed in the surface of the break some connection to what is going on in the world. Since then, I've tried as much as I can to examine what the damaging of art means, especially if entire communities or ideologies systematically go about doing it.

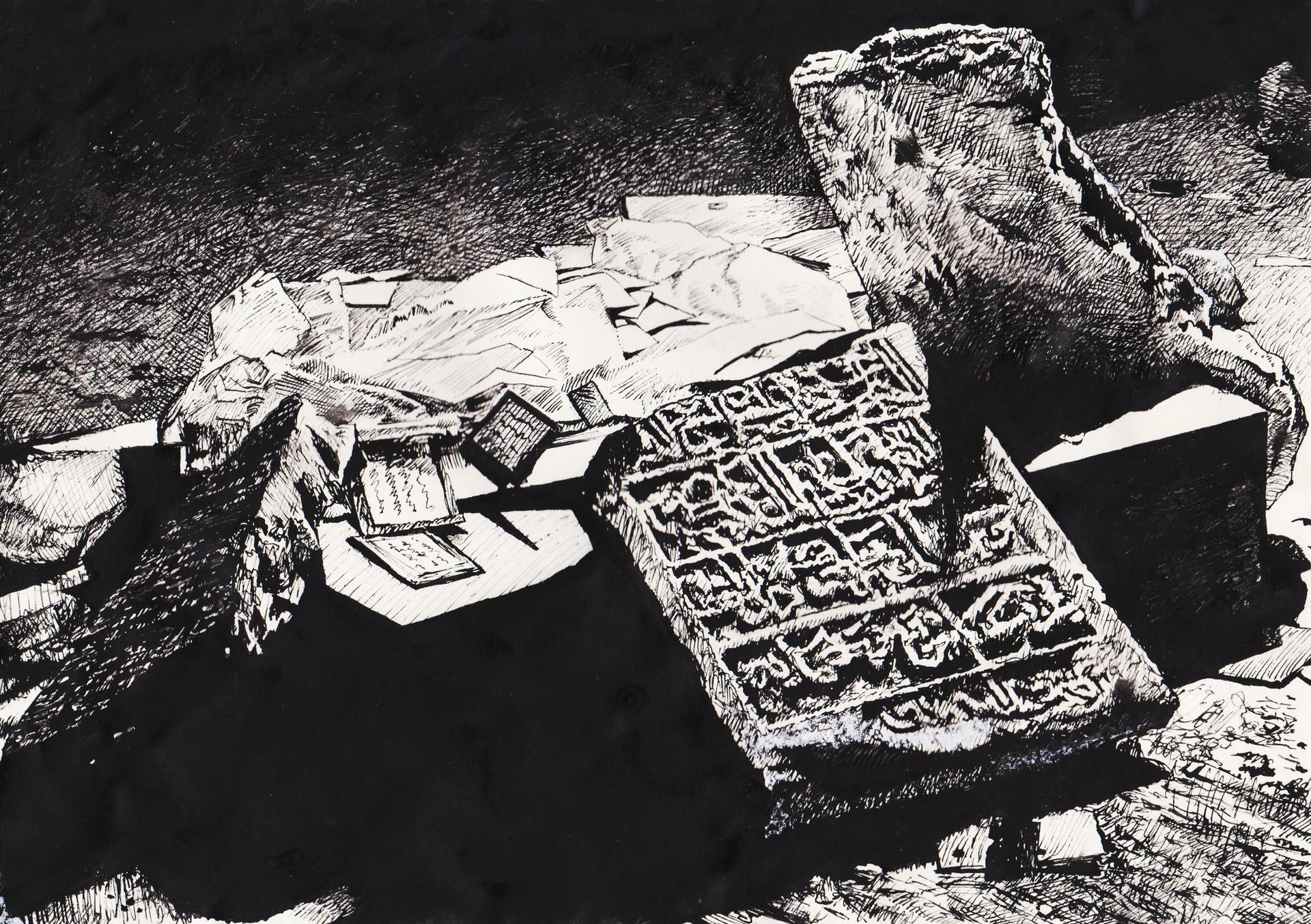

Piers Secunda's Mosul Museum Ruins (2019) is a drawing made from Mosul Museum charcoal reduced to ink Courtesy of the artist

You have started to create drawings out of charcoal that you have collected from burned out buildings, such as the Mosul Museum. Can you tell me about this new development in your work?

Before Isis left they burned large parts of the Mosul Museum, from the pedestals and interior of the exhibition halls to the ancient manuscripts in the basement’s comprehensive library. I have some of the burned remains from there. I also have a lot of charcoal from the Church of the Immaculate Conception in Qaraqosh, a Christian community about 30-minute drive from Mosul. Isis took out all the books there and burned them.

I’ve used the charcoal to make small scale drawings of the places where the material once came from—the Mosul museum and the church—which I draw from photographs I’ve taken. The ink is made by grinding down the charcoal with a mortar and pestle, mixing it with alcohol, and then adding gum arabic, which fixes the fluid and the pigment to the surface of the paper.

I find drawing to be quite refreshing. For my paintings I spend hour after hour, day after week after month, looking at the texture of the destruction made by Isis or the Taliban. Making the works involves buying different materials, securing military assistance, getting on aeroplanes and trying to avoid very, very serious danger. Drawing by comparison is like lightning—it's that immediate instant of expression and you can see the line grow. And from it, you can decide whether you're doing something right or it's going in a direction you didn't want; you can pull it back, you can push it in another way.

Piers Secunda making a moulding of the broken texture of an Assyrian sculpture inside the Assyrian Rooms of the Mosul Museum after they were attacked by Isis Courtesy of Zed Productions

Do you have plans to show the drawings?

A couple of people have expressed interest in showing them. It's probably a little bit premature to say. But I think that once there is a large enough volume of the drawings it wouldn't be too difficult to put together an exhibition.

What other shows do you have coming up?

I have a solo exhibition opening next month at the University of Houston Art Gallery (Piers Secunda: ISIS Paintings, 12 September-18 December), which will include a painting made with the Isis bullet holes as well ten drawings of Kurdish textiles made with indigo ink. Those drawings will then go on show at the Kurdish Textile Museum in Iraq. Then the exhibition Cultural Destruction Paintings, which opened at the Iraqi ambassador’s residence in London, will travel to Warsaw to be displayed at the Kurdish Regional Government (KRG) office. It’s a continued collaboration between the KRG and the Iraqi embassy, and I’m really pleased because it shows the work has had a diplomatic effect in Realpolitik.

According to the Syrian government, Isis’s strongholds have now been recaptured and the movement has been pushed into the digital sphere. In terms of your work, what kind of destruction do you plan to look at next?

I'd really like to see the damaged libraries in Mali and I’d very much like to go to Syria. I’d like to make work that is a celebration of what was there, as well as a documentation of what has happened to it. I have a picture in my head of a large Corinthian capital, completely intact, less a thousand years or so of wear and tear from the elements, lying on grass. And I think that it would be a very heartening experience for me to be able to make something that acknowledges the wholeness of something that was targeted in such a ferocious way. It is like a testament of survival.