Being pale and male is rapidly going out of fashion at auction and, as a result, demand—and prices—for women artists of different ethnicities is on the rise. Nowhere is this more evident than in the African art market where four women lead in terms of auction prices.

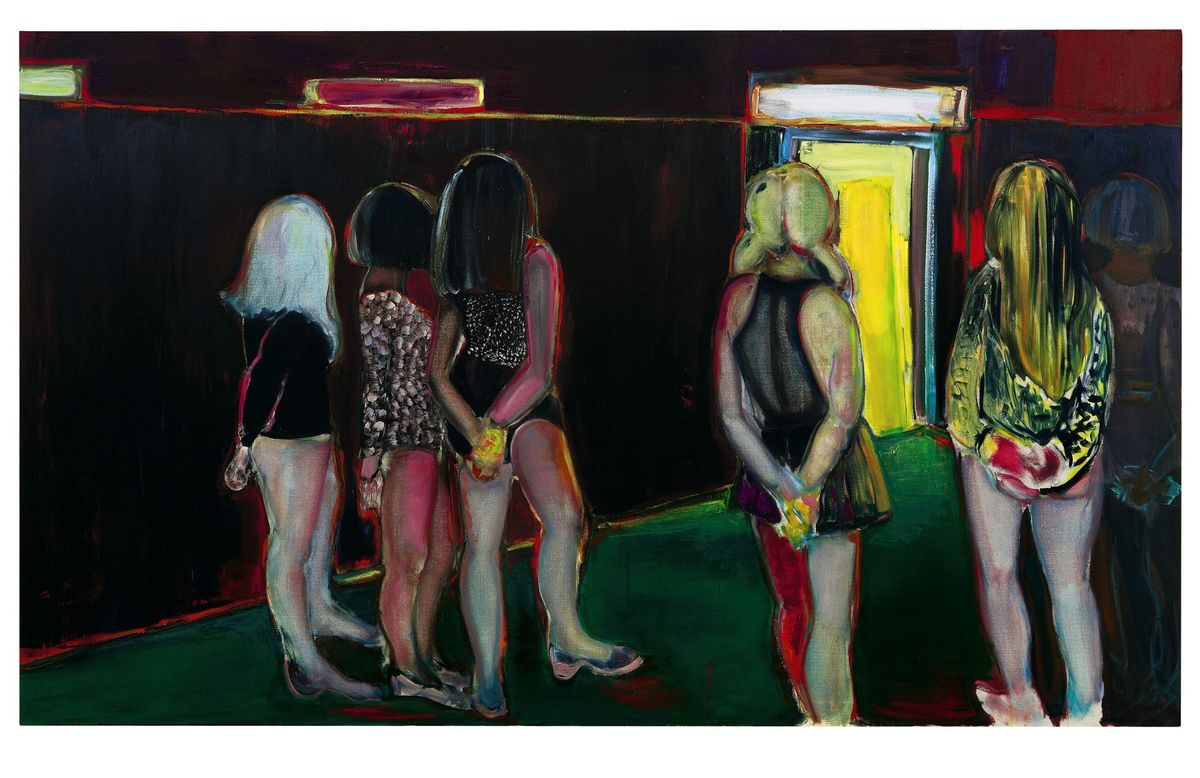

They are: Marlene Dumas ($6.3m), Julie Mehretu ($5.6m), Irma Stern ($4m) and Njideka Akunyili Crosby ($3.4m). Their prices eclipse the likes of Nigeria’s star Modernist painter Ben Enwonwu ($1.7m), El Anatsui ($1.5m) and William Kentridge ($1.5m).

It should be noted that two of the four women are white and only one—Irma Stern—lived on the continent until she died in 1966, in South Africa. Indeed, Marlene Dumas could equally be considered European (she has lived in Holland since 1976, representing the country at the Venice Biennale in 1995), while Ethiopian-born Julie Mehretu is based in New York and Nigerian-born Njideka Akunyili Crosby in Los Angeles.

These factors all complicate the picture, but, put simply, African women are in demand because buyers and sellers are “looking to fill gaps in the market”, and these artists meet both criteria (being female and African), says Hannah O’Leary, the head of Modern and contemporary African art at Sotheby’s. “The growing market for African artists often addresses two demands, being the lack of both ethnic and geographic diversity in the mainstream art market.”

Last week, a study by Sotheby’s Mei Moses revealed a similar pattern of female artists outperforming men in repeat auction sales—again, a matter of the “overlooked” being “rediscovered”. Meanwhile, an ArtTactic report published in July looking at auction sales of Modern and contemporary African art between 2016 and 2019 found that the average price for female artists has been consistently higher than men. In 2019, women fetch on average $91,338, compared with $19,555 for men. However, the number of lots sold by male artists far outweigh those by women: 680 versus 131 in 2019.

A perfect storm

The auction market for African art is an anomaly for other reasons too. Many artists come to the block without established secondary markets or previous auction records, while many of the older generation have gone their whole lives without gallery representation.

This presents a unique opportunity for auction houses, and can even help level the gender playing field, according to O’Leary. “We have an opportunity to make sure we get it right with regards to gender balance from the get-go in a way my peers in other departments cannot do because they rely so heavily on auction precedent,” she says.

However, the newness of the market can pose problems when it comes to pricing particularly when an artist’s market ascends rapidly. Akunyili Crosby is a case in point. Just two years after being signed by Victoria Miro gallery, Akunyili Crosby first appeared at auction in September 2016 when an untitled work from 2011 sold for nearly $100,000 with fees. Within two months she broke the $1m mark and within six months her work was commanding more than $3m. She achieved her record for Bush Babies (2017) at Sotheby’s in New York in May 2018.

O’Leary recalls early discussions with her colleagues in the contemporary department about how to value one of Akunyili Crosby’s paintings for the first time: “It was a matter of, what do we say? We knew the retail was under £100,000 and we knew that everyone wanted one. It was kind of a perfect storm when it came to her.”

Still woefully undervalued

Despite the positive strides being made by women in this field, O’Leary sounds a note of caution. “The story is more about African artists being undervalued. If you look at the market as a whole, Africa is still so under represented, it’s less than 1%,” she says. “We have such a long way to go before we actually see a true representation of diversity, but we are witnessing the beginnings of that.”

As the makeup of collectors begins to evolve in salerooms around the world, it is likely we will see a broadening of tastes. As O’Leary says: “It used to be that we knew who all our biggest buyers are, because they were those old-school blue-chip collectors from the same family. But now, the whole world has opened up.”