This elaborate and incredibly intricate casket with trompe l'oeil marquetry and engraved ivory and bone panels was in the collection of the marquesses of Lothian at Newbattle Abbey, near Edinburgh, until 2017 when it was sold at Sotheby's. Estimated at a mere £50,000-£100,000, it sold for £118,750 (with fees)—a steal, surely. Now attributed to the so-called Master of Perspective due to its likeness to 11 similar works of South German marquetry of the same period, it being shown during London Art Week (until 5 July) in the hope of finding a UK buyer. In April, the UK's then arts minister Michael Ellis placed a temporary export bar on the cabinet as it is believed to be the only known example of its type in the country. Time is running out—the decision on the export licence will be made on 11 July but, according to a government statement: "This may be extended until 11 October 2019 if a serious intention to raise funds to purchase the casket is made at the recommended price of £750,000." One of the earliest known examples of kunstkammer (cabinet of curiosities) furniture, the cabinet is thought to have come into the possession of the Scottish family when the 4th Marquess of Lothian married the granddaughter of the 3rd Duke of Schomberg, 1st Duke of Leinster, in 1735. The Renaissance Court Casket of Newbattle Abbey by the Master of Perspective, Nuremberg (1565). Georg Laue, Kunstkammer and Trinity Fine Art, London, until 25 July. Around £700,000. (Courtesy of Georg Laue, Kunstkammer Ltd and Trinity Fine Art)

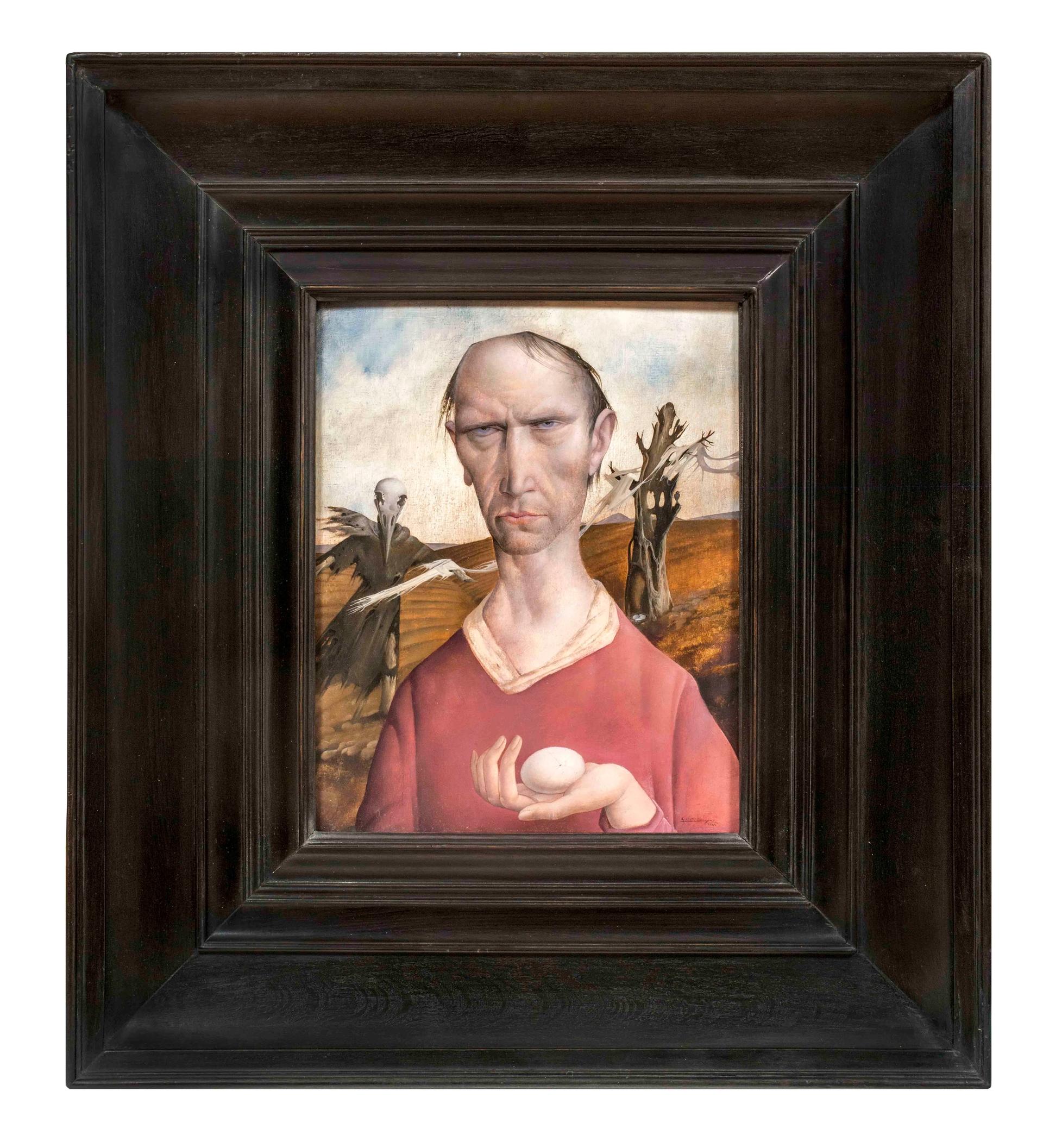

The New York-based dealer Ambrose Naumann has an eye for disquieting, unsettling images, as is shown in his debut London Art Week exhibition, titled Lines of Time, in collaboration with Tomasso Brothers Fine Art. Naumann is showing a group of works on paper by Walter Sauer (1889-1927) and Nicolas Eekmann, and seven huge, lurid religious and/or allegorical works by Marcel Delmotte (1901-1984), depicting subject such as Christ on the Cross and Dawn of a New Era—all accompanied by figurative sculptures with a similar sense of line and subject from the Tomasso Brothers large inventory. But most hauntingly peculiar is this little egg tempera work by the little-known Belgian artist Gustaaf De Bruyne. "He suffered from diabetes and this was done around the time of his life when his doctors said 'move out of the city [Brussels], live a less stressful life'," Naumann says. "We think it's a self-portrait because it looks like him, but we don't know that for sure." He adds: "It's got this weird psychological feeling: the cracked egg, the figures behind. Feelings of why is this happening to me? De Bruyne died after he lost the use of his hands from diabetes—his wife said he died because he couldn't paint anymore." Gustaaf C. De Bruyne, Waarom (Why, 1961). Lines of Time, Ambrose Naumann Fine Art at Tomasso Brothers Fine Art, London, until 5 July. Asking price $75,000. (Courtesy of Ambrose Naumann Fine Art )

For this year’s London Art Week (until 5 July), Sam Fogg mounts a show that aims to show the breadth of craftsmanship during the Middle Ages. The objects, from vestments to metalwork, took 20 years to accumulate and, considering how many works of art were destroyed through war and iconoclasm, they are lucky to survive. Among them is this lewd ithyphallic gargoyle, which proves that Britain’s base sense of humour is nothing new. The gallery’s Matthew Reeves says: “Big gargoyles like this, with quirky (!) details, are extremely hard to find. It has a very sexualised content not just because of the obviousness of the appendage but also because it directly echoes the function of the gargoyle, to spurt water out of the open mouth at the top.” An ithyphallic limestone gargoyle, England (late 14th century). Medieval Art in England, Sam Fogg, London, 27 June–26 July. Between £20,000-£30,000. (Courtesy of Sam Fogg)

This is Antiques Roadshow gold: an antiques dealer buys a chess piece for £5 in 1964 Edinburgh and now it might sell for £1m. The “new” Lewis Chessman, a little walrus ivory warder, is from a hoard of 93 medieval chess pieces found in 1831 on the Isle of Lewis off of Scotland. Of those, 82 are in the British Museum in London. Sotheby’s Alex Kader says, the “warder is made of walrus ivory and therefore not currently subject to any of the legal restrictions.” But, the UK government is now considering a wider ban, including walrus. A Lewis Chessman, probably Norwegian (12th or 13th century). Old Master Sculpture & Works of Art, Sotheby’s, London, 2 July. Estimate £600,000-£1m. (© Getty Images)

This portrait of a praying nobleman is one of a handful autograph works by the Netherlandish painter Hans Memling to come to auction in the past decade. Originally the left panel of a triptych, it has been restored several times, most recently at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston between 2003 and 2009. Here, Memling's nobleman received something of a reverse-facelift—the subject's feet and hands had been repainted to give him a much more youthful appearance but were restored in Boston based on surviving passages of Memling's original paint surface, resulting in the more wrinkled face visible today. During this process, the curved section of gilt metalwork adorned with red and blue stones in the painting's upper left section was also uncovered. Appearing to occupy an intermediate space between the viewer and the kneeling subject it likely relates to a trompe l'oeil element that was painted onto the original frame. During the 1950s, the painting was on long-term loan to the Mauritshuis in The Hague but was bought in 2001 by the present owner from the collection of the Ohio TV syndication mogul Frederic W Ziv. Hans Memling's Portrait of a member of the De Rojas family, kneeling (15th century). Christie's Old Master evening sale, London, 4 July. Estimate- £1.5m-£2.5m. (Courtesy of Christie's)

Laughter is rarely depicted in the work of Jusepe de Ribera, the Spanish Baroque artist better known for torturing his subjects in paint, as shown at the acclaimed exhibition of his work at London’s Dulwich Picture Gallery last year. That might explain why this arguably more commercial depiction of a smiling girl is priced very confidently at £5m-£7m—if it reaches that pitch, it will break Ribera’s auction record (set a decade ago at Sotheby’s London sale of the Barbara Piasecka Johnson collection when Prometheus sold for £3.8m with fees). Painted at the height of Ribera’s career, when the artist moved to Naples, the work—whose subject is as much about the noise of the tambourine as it is the girl herself—is thought to be one of a series of five works in which Ribera depicts the senses, with this one representing sound. It last appeared at auction at Sotheby’s in 1997 when it sold for £1.8m (with fees), and was sold the year after to the present vendor. K.J. Jusepe de Ribera, Girl with Tambourine (The Sense of Hearing, 1637). Old Masters Evening Sale, Sotheby’s, London, 3 July. Estimate £5m-£7m. (Courtesy Sotheby’s)

Rescued from the ruins of a villa owned by the Roman Emperor Antoninus Pius, who ruled 138-161 AD, these calcified canines were some of the first acquisitions made by the British art collector Thomas Hope during his Grand Tour (the 18th-century equivalent of the gap year). With a love of the classical world and an enormous family fortune, he amassed a collection of ancient Roman marble sculptures, with these hounds dutifully standing guard in the Statue Gallery of his Marylebone townhouse. Partially restored in the 18th century (hence the fairy low estimate), they were passed down to Hope’s eldest son Henry; this is their first time at auction since 1911. Two Roman marble figures of Celtic hounds (around 2nd century AD). Antiquities sale, Bonhams, London, 3 July. Estimate £200,000-£300,000. (Courtesy of Bonhams)

This elaborate and incredibly intricate casket with trompe l'oeil marquetry and engraved ivory and bone panels was in the collection of the marquesses of Lothian at Newbattle Abbey, near Edinburgh, until 2017 when it was sold at Sotheby's. Estimated at a mere £50,000-£100,000, it sold for £118,750 (with fees)—a steal, surely. Now attributed to the so-called Master of Perspective due to its likeness to 11 similar works of South German marquetry of the same period, it being shown during London Art Week (until 5 July) in the hope of finding a UK buyer. In April, the UK's then arts minister Michael Ellis placed a temporary export bar on the cabinet as it is believed to be the only known example of its type in the country. Time is running out—the decision on the export licence will be made on 11 July but, according to a government statement: "This may be extended until 11 October 2019 if a serious intention to raise funds to purchase the casket is made at the recommended price of £750,000." One of the earliest known examples of kunstkammer (cabinet of curiosities) furniture, the cabinet is thought to have come into the possession of the Scottish family when the 4th Marquess of Lothian married the granddaughter of the 3rd Duke of Schomberg, 1st Duke of Leinster, in 1735. The Renaissance Court Casket of Newbattle Abbey by the Master of Perspective, Nuremberg (1565). Georg Laue, Kunstkammer and Trinity Fine Art, London, until 25 July. Around £700,000. (Courtesy of Georg Laue, Kunstkammer Ltd and Trinity Fine Art)

Object lessons: London Old Master season special

Our pick of highlights from London Art Week exhibitions and auctions, including an export-barred Renaissance cabinet and an uncharacteristically cheery Ribera