Sotheby’s Impressionist and Modern art evening sale in June 2018 was described by one dealer, perhaps harshly, as a “car crash”, overshadowed by Christie’s more upbeat affair. But auctions are fickle things and this year, with better material than Christie’s, Sotheby's came out tops with a £84.8m (£99m with fees) total from a small—sorry, tightly curated—sale of 25-lots last night.

Last night’s sale may have been smaller than the 2018 auction (of 36 lots) but it was more efficient and steadied some market jitters—the sell-through rate of 92% was, Sotheby’s says, the highest for an evening sale in the category in London since 1988. Fun fact for finance geeks: that was the year, points out my colleague Melanie Gerlis, that Sotheby’s was listed on the stock exchange. Now, of course, it is being taken off following the surprise sale of the company just two days ago.

However, seven of last night’s works were essentially pre-sold via third-party guarantees. On Monday, there were five guarantees, four of them house guarantees. By last night, all of the house-guarantees had been off-set to third parties and a further two works were guaranteed by third parties: Picasso’s Buste d'homme, (est. £1m-$1.5m) and Pierre Bonnard’s Nu assis, jambe plieen (est. £800,000-£1.2m). It appears a fair few of the guaranteed lots sold to their guarantor—bidding was shallow on many of the larger lots and it was sometimes hard to see where the auctioneer Helena Newman was taking them from. But perhaps that was the lighting.

Auctioneer Helena Newman in front of Monet's waterlilies scene Nymphéas (1908) Courtesy of Sotheby's

In New York last month, Sotheby’s set a new record for Monet when Meules (1890) from his haystacks series sold for $97m ($110.7m with fees). That sale, says Sotheby’s Thomas Boyd-Bowman helped persuade the owners of Monet’s waterlilies scene Nymphéas (1908) that now would be the time to part with it—the painting had been bought by the family in 1932 and had never before been at auction (a huge 64% of works in last night’s sale were making their auction debut). This rather wan, pale work, estimated at £25m-£35m, carried the biggest guarantee of the night and seemingly sold to the guarantor—with not much interest, it sold to Sotheby’s Simon Shaw (bidding for a client, but not on the phone) below estimate at £21m (£23.7m with fees), making it the top lot of the sale.

From the same collection as the Monet, apparently from Argentina, came two more bucolic Impressionist works, both guaranteed by third parties—another Monet, the blustery Printemps a Giverny (1885), which sold for well under its £4m-£6m estimate at £2.6m (£3.1m with fees) and Camille Pissarro’s Les meules et le clocher de l’église à Eragny (1884), sold at a low-estimate £1.2m (£1.6m with fees).

Newman coaxed tortuously slow bidding on Modigliani’s lovely Jeune homme assis, les mains croisées sur les genoux (1918, est. £16m-£24m), which had been in the same family collection since it was bought from Modigliani’s dealer Léopold Zborowski in 1927. This is one of only ten known paintings of anonymous boys painted by Modigliani at the end of the First World War when he left Paris for Cannes, leaving behind his usual, more glamorous subjects and started painting bell boys and butcher’s boys instead—shades of Chaïm Soutine here. The surface is more textured than usual for Modigliani, the treatment “less glamorous, more simple and sympathetic” says Boyd-Bowman.

Joan Miró's Peinture (L'Air) (1938) Courtesy of Sotheby's

The hierarchy of value for Modigliani’s work is marked; with his female subjects, particularly nudes, are the most highly prized—two nudes have sold for in excess of $100m. Last time one of these 1918 works came up for sale was at Sotheby’s New York in 2006 when Le fils du concierge sold for a huge £31m (with fees). But that painting was crisper, more haunting and last night’s version did not reach such great heights—with three dithering phone bidders, it sold on its low estimate at £16m (£18.4m with fees), probably to an Asian bidder via Sotheby’s Patti Wong’s phone, the second highest lot of the sale.

Miró’s impish Peinture (L’Air) (1938) was painted while the artist was in exile in Paris as a response to the Spanish civil war (some suggest the serpent is Franco) and is a pre-cursor to the artist’s sought-after Constellations series. This work had last appeared at auction at Christie’s New York in 2010 when it sold under-estimate at $10.3m with fees. Last night, the vendor got a slim return as it sold on the phone to the guarantor for £10.4m (£12m with fees).

The New York-based art advisor Mary Hoeveler thinks the Miró “a really good painting” and says that thin bidding can be misinterpreted: “In most cases, there are only two or three people who are going to be bidding at that level on a work. That was a lesson from the Leger at Christie’s [which did not sell on Tuesday]—if one person drops out at the eleventh hour and doesn’t bid, it has a big impact. The market makes a big deal out of these things, but it reality it’s not indicative of anything other than a lack of excitement in the room and one or two key people not bidding.”

Hoeveler adds: “When the Leger didn’t sell at Christie’s on Tuesday night, it sucked the air out of the room for the Surrealist material. It’s all very psychological. It’s like a game of chicken: you’ll have someone on the phone waiting for someone else to bid before they jump in, and meanwhile the painting is the painting is the painting.”

Camille Pissarro's desirable Le Boulevard Montmartre, fin de journée (1897), sold for £7.1m with fees Courtesy of Sotheby's

At Sotheby’s there was, of course, a smattering of late Picasso works, now a pre-requisite in these sales—mainly the slightly arthritic swaggering musketeers painted by the artist in his dotage. Here the Picasso’s were led by Homme à la pipe (1968), a musketeer at auction or the first time, which sold for a mid-estimate £6.5m (£7.6m with fees) in the room to the Indian collector Cyrus Poonawalla—a keen racing enthusiast and racehorse owner, he is probably in town for Royal Ascot.

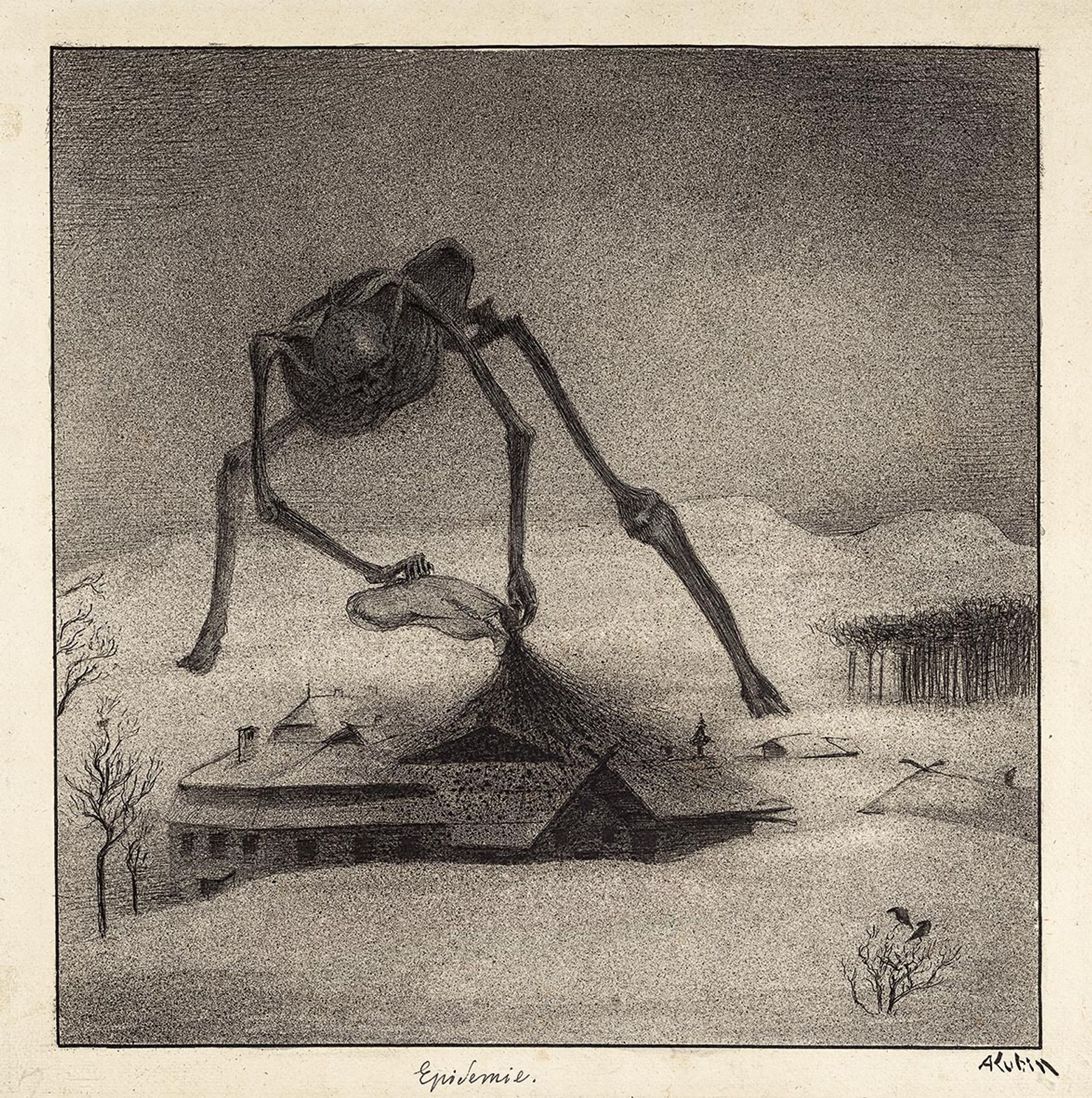

Though many of the top lots were to some extent a foregone conclusion, thanks to their guarantees, more invigorating were two works by artists who rarely appear at evening sales. First, the sinister pen and ink work Epidemie (Epidemic) by Alfred Kubin, which came from a group of 16 early works on paper by the Austrian artist which were formerly in the collection of his patron Max Morgenstern and have been restituted from Munich’s Lenbachhaus museum to the heirs of Max and Hertha Morgenstern (the remaining 15 will be offered today). Modestly estimated at £150,000-£200,000, the work was competed by the dealer Richard Nagy, who held the first solo-show of Kubin’s work in 2017. But it was an online bidder who ended up buying it, for £790,000 (£963,000 with fees)—triple the previous artist record.

“Great works on paper do well in London—for instance, the Kubin, I‘m not sure it would have done so well in New York,” Hoeveler says. “It’s a wonderful, masterful work with a great provenance by an artist who doesn’t often come up.”

Epidemie (Epidemic) by Alfred Kubin Courtesy of Sotheby's

Utterly different but also unusual was the abstract Relational Painting, No. 60 by Fritz Glarner—the first time the Swiss-American painter has been included in an evening sale, this work was being deaccessioned by the Museum of Modern Art. “Glarner was a friend of Mondrian’s and this comes at a moment when people are very interesting in the de Stijl and Bauhaus movements. Collectors like to make the connection between what was happening in Europe and the US at that time, that sense of cross-pollination of ideas,” Boyd-Bowman says. Without a guarantee, it sold to James Mackie’s phone-bidder for almost the top-estimate, £620,000 (£759,000 with fees).

Reflecting on this week’s sales, Hoeveler says: “You can see the difficulty both houses have in getting material. The sales are getting smaller and smaller in London, while those in May in New York were enormous. There’s a general sense of market fatigue after all the fairs, plus the uncertainty around Brexit makes people reluctant to consign. It’s a knock on effect.”