It is a tough market for American art, at least where the paint has had time to dry. In the wake of last week's strong "Giga week" auctions in New York, Sotheby's and Christie's American art sales, held this Tuesday and Wednesday, were a let down. Seventy of Christie's 86 lots sold. Yet unlike Sotheby's, they aligned seller desires with market realities. With 33 of its 85 lots bought in, Sotheby's has to be mortified by so many flops.

Bolstering Christie's sale was undoubtedly its Modern offerings. Possibly one of the finest collections of American Modernist painting in private hands, assembled quietly and expertly by Michael Scharf, was sold. The star of the collection—was the big, bold Abstraction by Marsden Hartley from around 1912, which set a new record for the artist. Estimated at $4m-$6m, it sold for $6.7m (with fees) after lengthy bidding that was less like a war than a crazy chess game, except one by committee. Phone bidders took forever to go higher, consulting calculators, accountants, wives, husbands, paramours, prospective heirs, decorators, psychics, astrologers—who knows? I have worked with many collectors of American Modernism over the years and sometimes it seemed every day for them is a full moon.

Scharf's collecting started with works by Arthur Dove, whose work he first bought in 1972. River Bottom, Silver, Ochre, Carmine, Green from 1923 and the priciest of his Doves at a $3m-$5m, was withdrawn from the sale and, I assume, sold privately. Dove's Nature Symbolized No. 1 (Roofs) made $1.9m, approaching the high estimate.

A Georgia O'Keeffe, also from the Scharf collection—a small, luscious red canna from 1919—seemed perfect for the market but its $4m-$6m estimate was too high. It was bought in at $3.8m. Its flop is a shame since it is a work from when O'Keeffe was among the most inventive artists in the circle of Alfred Stieglitz: it represents a rare still life, portrait and "flower interior," a narrow genre at which the artist excelled. It is dazzling, but it is precious and in our age of gigantism, that is undervalued.

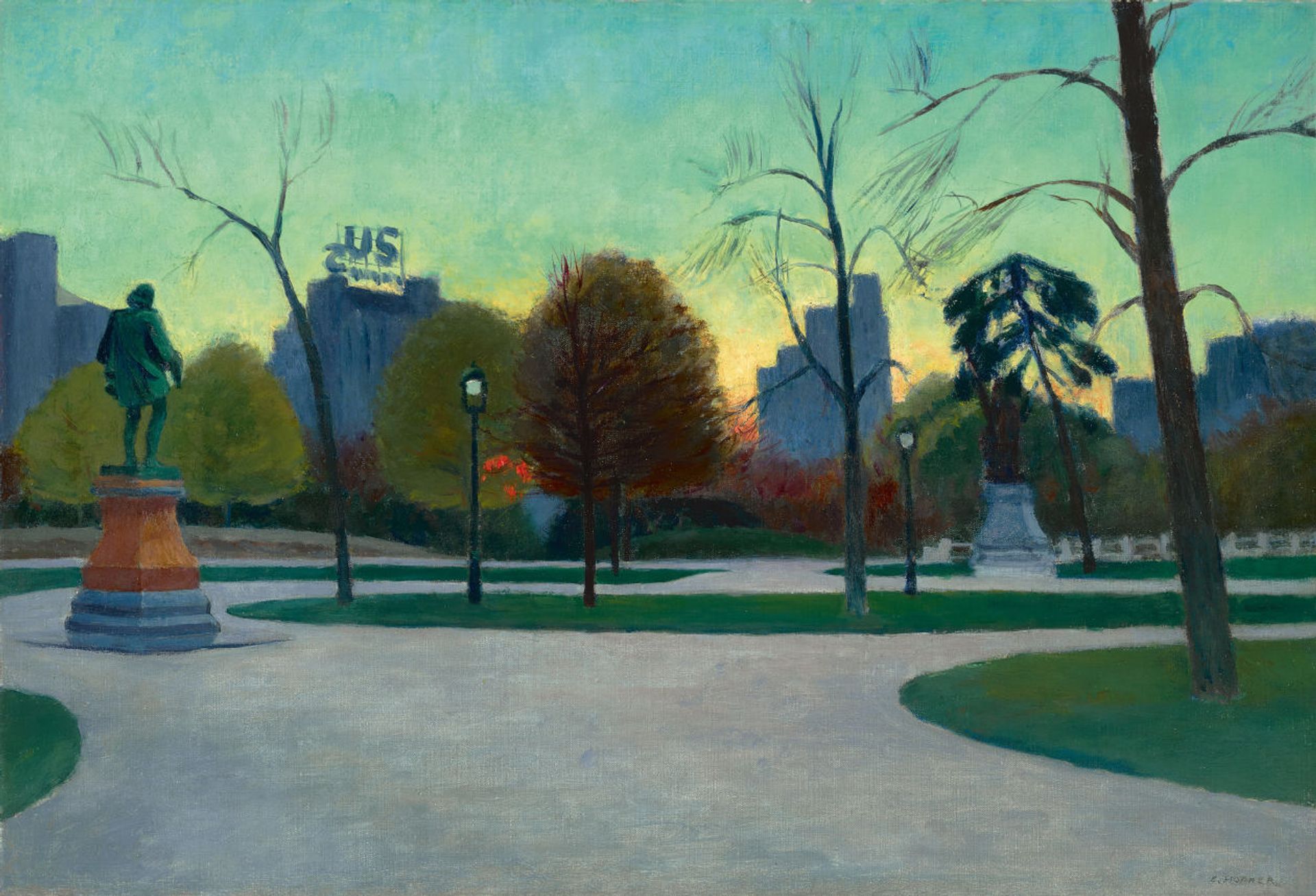

Hopper's Shakespeare at Dusk flopped at Sotheby's Courtesy of Sotheby's

At Sotheby's, prices for Modern works were all over the place. Another O'Keeffe, Waterfall, No. 2, Tao Valley from 1939, went for $760,000. Its success is a bit of an oddity since the work is counterintuitive for O'Keeffe: it is a waterfall, not a flower, a Hawaiian picture, and green, which is not her signature colour. Even more curiously, Seated Female Form from the early 1910s by Elie Nadelman failed to sell in the same sale. Though gorgeous and never before seen on the market, perhaps the estimate, $600,000-$800,000, was too high. What was certainly too high was the $7m-$10m estimate on Shakespeare at Dusk by Edward Hopper. Ultimately it is a minor picture and a derivative cityscape. Not even the dearth of available Hoppers could salvage it.

The market for Hudson River School works has been moribund since at least 2007—the great things still sell but the middle market barely has a pulse. Yet there were a few strong sales in the category worth noting. Sanford Gifford's magical A Lake Twilight from 1861 spurred a bidding war at Sotheby's. It went for $2.4m (with fees), a record for Gifford and well above its $1.2m-$2m estimate. Burdening this little dynamo, however, was a massive, gilded carbuncle of a frame. The underbidder bought a smaller, sublime Gifford from 1876 minutes later for $187,000 (with fees), more than twice the high side on a $60,000-$80,000 estimate.

Other than these, Sotheby's Hudson River offerings faced mostly a dry hole. At Christie's, the ethereal On the Coast by John Kensett sold at the low estimate, $495,000 (with fees). It is a gorgeous, abstract late picture. Other fine Hudson River works at Christie's by Kensett, Gifford, and Albert Bierstadt, however, barely crawled past the "sold" hammer mark at just below the low estimates or did not sell at all.