The Federal Bureau of Investigation’s (FBI) art crime team is seeking help to return thousands of objects, works of art and Native American human remains that it seized in 2014 in Waldron, Indiana, from the property of the late ethnographic collector Don Miller. Officials confiscated around 8,000 pieces from a trove of more than 40,000 objects from various cultures, with around a third of the collection comprising Native American art works and human bones. “The sheer size of the collection and human remains was shocking”, says FBI special agent Tim Carpenter. “It’s unfortunate, but not uncommon, to find some human remains in these types of seizures, but we were certainly not prepared for what we found”.

Since the case surfaced, the department has repatriated around 12% of the collection, including sending objects back to China, Spain, Colombia, Mexico, Canada, Peru, Cambodia and Iraq. But returning the illegally removed Native American materials has proved more challenging because “there’s simply no single expert on all these objects”, Carpenter says. The FBI has been consulting with scholars and museums, but any debate over the origin of specific pieces can slow the process.

The sheer size of the collection and human remains was shocking

A notice was issued through the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) last year regarding a female skull from Miller’s collection which was removed from, or near, an area on the Missouri River known to have been populated by several tribal nations. But because NAGPRA is primarily intended to deal with museum collections rather than serve law enforcement, and because the origin of various items remain unclear, the FBI chose to forego filing further notices through the NAGPRA system.

Instead, the FBI has launched an invitation-only website containing images and known information about the seized objects. Each section has access controls that limit who can view what objects, out of respect for the cultures that may hold those works as sacred. “Native American leaders get access to a portion of the website that contains Native American and unknown materials and vice versa for other cultures, because it’s not useful or respectful to give, for example, a Romanian archaeologist access to sensitive Native American objects,” Carpenter says. Images of the recovered bones will only be shared on a case-by-case basis with tribal representatives.

The seized items are now held in a temperature-, light- and humidity-controlled facility near Indianapolis, where they are being safeguarded and prepared for their return by museology and anthropology graduate students of the Indiana University-Purdue University.

Miller, a former member of the army reserve who reportedly worked on the Manhattan Project (the US-led effort to develop nuclear weapons during the Second World War), was also a world-travelling Christian missionary. As a hobby, he spent his spare time on amateur archaeological digs, which “sometimes crossed the line into illegality and outright looting”, according to the FBI. Miller made no secret of his collection and often agreed to interviews. An article published by a local newspaper in 1998 describes his basement as “a museum with lighted-glass showcases lining the walls on three sides, with printed notes on where the objects were found and their age”, although most of the collection was not labelled. It notes that Miller had dinosaur eggs unearthed in China, an Amazonian dugout canoe, a Tibetan cowbell and hundreds of Native American arrowheads.

Miller was not arrested or charged after the FBI raid on his Indiana farm, and he died nearly a year later in March 2015, aged 91. His collection included Italian mosaics, pre-Columbian art, and artefacts from Russia, China and New Guinea. Last year, two mammoth tusks from Miller’s collection were returned to Canada and, at the end of February, the FBI sent 361 artefacts back to China at a ceremony at the Eiteljorg Museum in Indianapolis, marking the largest ever return of Chinese objects from the US.

Returning materials to Native American tribal governments will be a slower process, although there has been an rise in responses since the FBI put out a public call for information. “Part of our initial goal was to generate awareness around the case so that communities can come forward and engage with us because this kind of effort can’t exist in a vacuum,” Carpenter says. “I’ve signed up several dozen people to the website and I think that’s a very positive sign.”

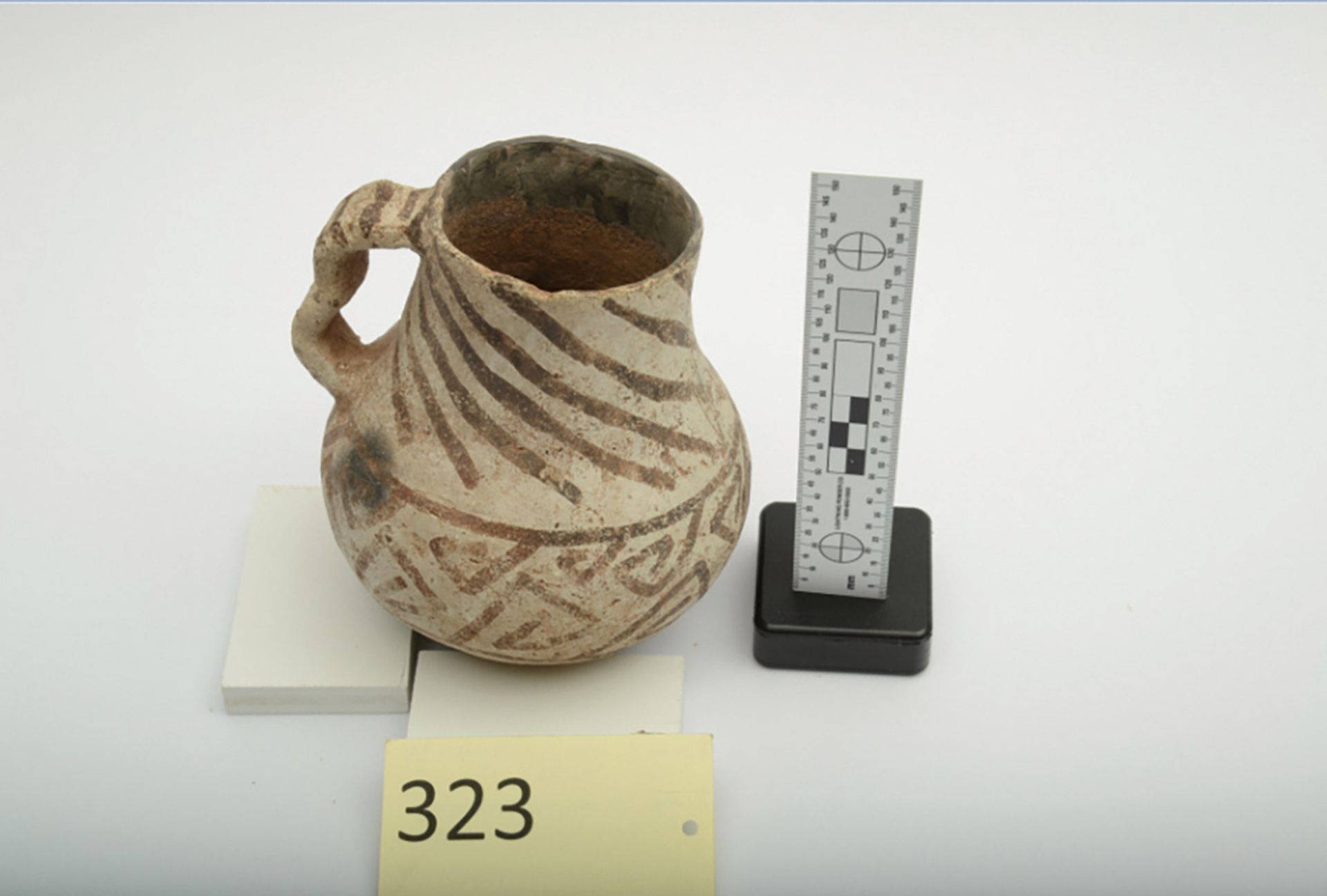

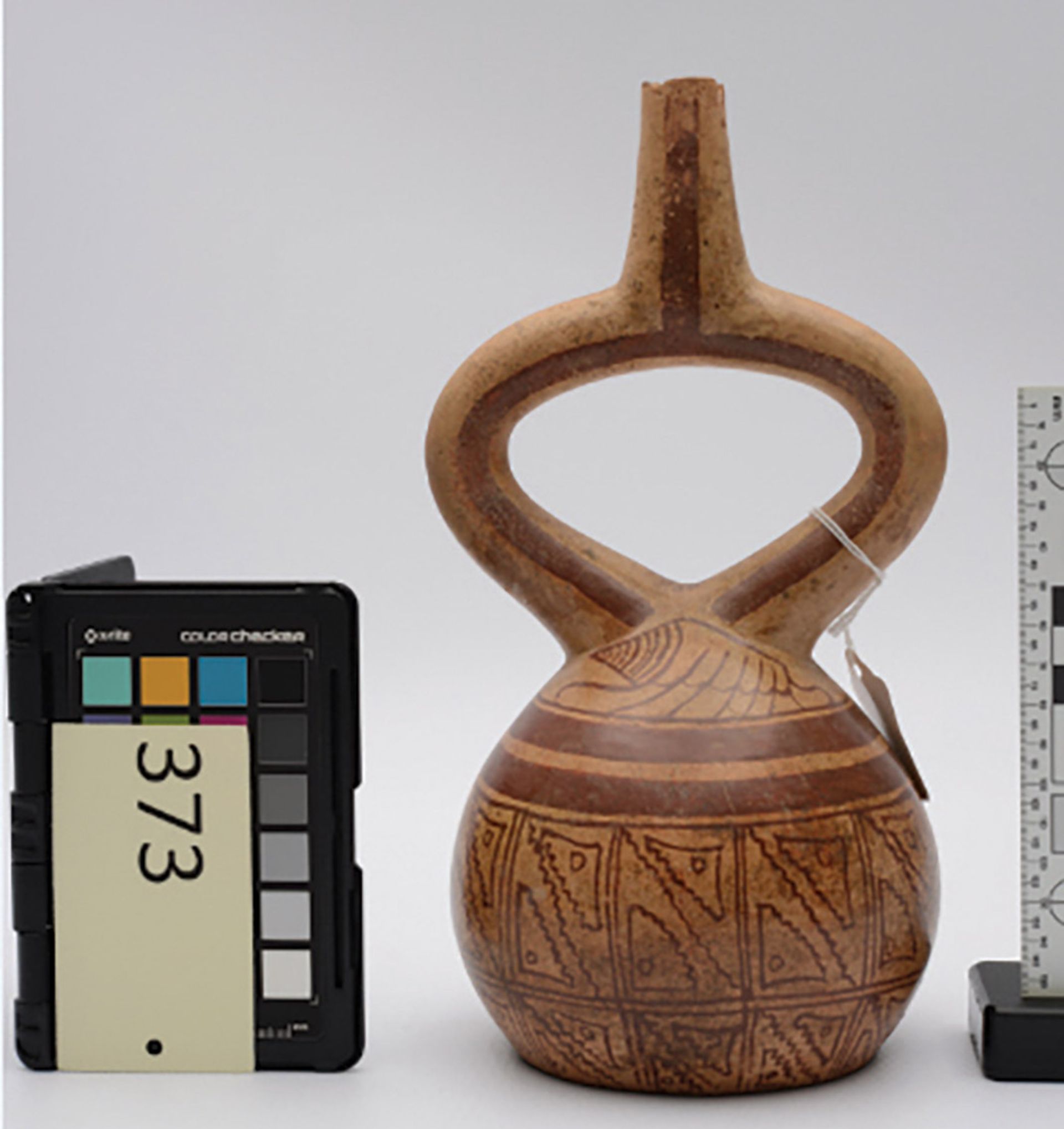

The FBI needs your help

Do you recognise any of the objects below? They are some of the items the FBI is seeking to identify before they can be returned. Representatives of Native American tribes and South American cultural specialists with information can email artifacts@fbi.gov.

Around a third of Don Miller’s collection is comprised of unidentified Native American and South American objects Images courtesy of the FBI