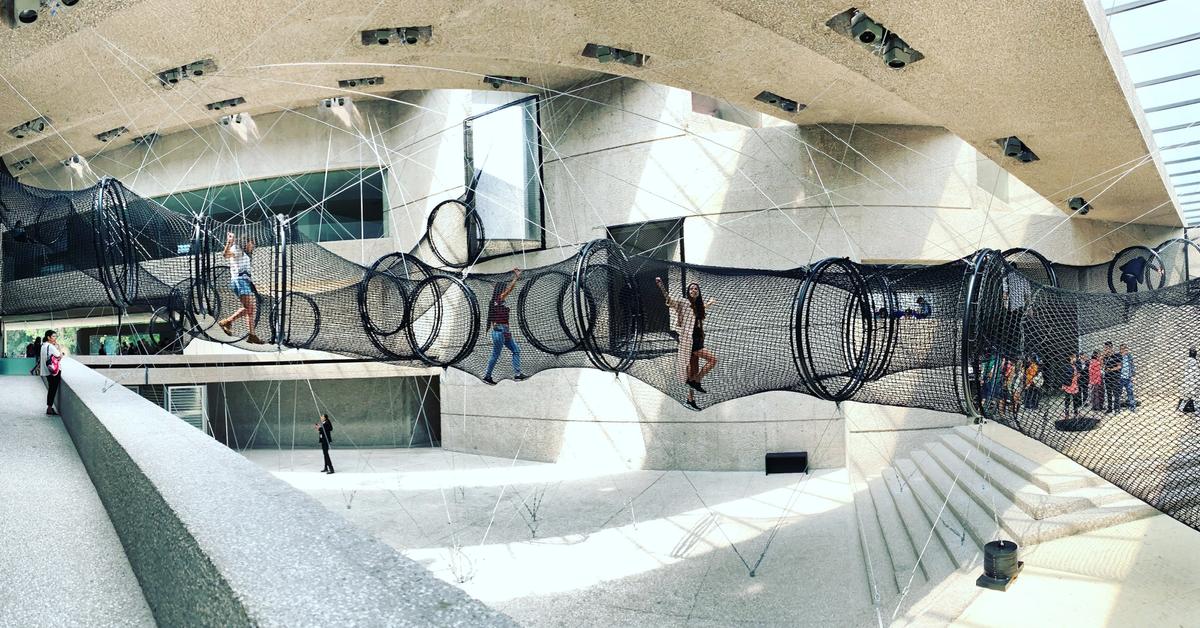

In the hot sun outside Mexico City’s Museo Tamayo, I squint up at Giant Triple Mushroom, Carsten Höller’s sculpture perched on the roof of the museum. As the finishing touches are being made on his first Mexican retrospective, Sunday, Höller gives me a sunburned smile and says: “It’s kind of a trap.” To reach the sculpture, visitors must climb through Decision Tubes (2019), mesh tunnels suspended in the atrium that lead to different parts of the museum. Over the past three decades, Höller has become known for his carnivalesque installations that playfully disorient visitors. Sunday does just that, with flashing lights, moving walls, mirrors, and mysterious pills.

These effects may not be pleasant, but for Höller, that is ideal. “I want to force you to get under the influence of what this does to you,” he says about the show’s most nauseating work, Light Wall (2000/2017), a floor-to-ceiling installation of light bulbs flashing on and off 7.8 times per second. He recommends visitors close their eyes to induce hallucinations. “I want you to feel like this is going on forever, wherever you are, it’s never going to be stable again.” As we linger in this room, yellow and blue tones begin to emerge and zigzagging diamond patterns waft across my retinas.

While this work’s dizzying light frequencies brings colour to the mind’s eye, visions of lushness also abound just beyond the museum’s doors in Chapultepec Park. Scores of vendors line up to display mountains of colourful chips, spicy fruits, and plastic toys to families strolling the park. People swarm around the Museo Tamayo on the opening weekend of Höller’s first major exhibition in Mexico, with attendance nearing around 6,000 visitors per day. The frenzy of entertainment inside the museum is a natural continuation of the spirited forms of public recreation outside.

Scores of vendors line up to display mountains of colourful chips, spicy fruits, and plastic toys to families strolling through Chapultepec Park Photo: Vanessa Thill

Perhaps because of this, the most effective work in the exhibition is Swinging Spiral (2010/2016), a spiral-shaped wooden room hung from cables that hovers just above the ground. To enter or exit the space, visitors must squeeze through a tiny gap. Inside, the walls sway softly, creating a sea-legged sense of unease. The museum docent ushers me “adelante”, to go ahead into the spiral, toward a tiny dead-end nook for a rare moment of peace.

Large-scale architectural works tend to be Höller’s forte, while the pieces that rely more specifically on pop culture come off as non sequitur and arbitrary. For example, Moving Image (1994-2004), a flickering slide projection of Mohammed Ali, is the only figurative image detectable in the exhibition. “Boxing is about movement,” Höller offers tentatively. I remain dubious of the function of this work, and the use of a black body as illustrative of a technical effect or abstracted dynamic. The absence of wall text in the exhibition leaves viewers guessing, causing several to write frustrated notes in the front desk’s comment book about difficulty navigating the show.

Yet provoking bewilderment is one of the artist’s primary goals. Red and white capsules drop from the ceiling into a pile in Pill Clock (2015), and viewers are encouraged to dose themselves. When I ask, “What’s inside?” he simply says, “Exactly.” It is hard to tell if these participatory, drug-themed works are offered ironically, especially given the recent spotlight on the Sackler family’s art-washing of their opioid fortune. But Höller’s work tends to candidly encourage a shift in perspective, rather than a pointed critique. His special “dream-enhancing” toothpaste, a work titled Insensatus Vol. 1 Fig. 1 (2014), has a shady new-age flair, when he explains that the work uses plant extracts meant to direct your dreams toward either the “female world”, the “male world”, the “world of children,” or a mix of these. Tubes are for sale in the gift shop, and provided to accompany Two Roaming Beds (Grey) (2015), a pair of twin beds on wheels that slowly swivel as red and blue markers streak the floor beneath them. Members of the public can reserve an overnight stay. Höller says grandly: “In the end it will be a big painting done by the dreams of the people.”

As we end our Sunday tour, I linger on this note. Is the city not already the result of collective, painted dreams? While Höller’s show presents an engaging and unusual opportunity to interact physically with works in a museum, intensely tactile and personal exchanges abound in Mexico City. I saw no better example of total participation than in the nightclub, Patrick Miller, where thousands crowd in on Fridays to dance with abandon, and cheer each other on. “The show sets up a triangle,” Höller says, between you, other visitors, and the objects you encounter. But I would argue that triangle is already vividly alive here. In the end, I think the artist would be pleased that one takeaway of the show is the reminder that striking experiences surround us in our everyday lives, and not just on Sunday.