Where a protest against McDonald’s spawned the Slow Food movement, so the blockbuster exhibition has inspired a Slow Art resistance. Anyone who has visited a “once-in-a-lifetime” exhibition will be familiar with the exhausting routine: queueing at the entrance, jostling with crowds around the masterpieces, fighting falling energy levels and mounting frustration. If photography is permitted, throw selfie sticks and Instagram posers into the mix too.

The global museums initiative Slow Art Day aims to be “counter-cultural to the smartphone and its growing dominance in culture, but also to blockbuster exhibits and the focus on absolute numbers”, says Phil Terry, the US e-commerce entrepreneur who founded the annual event in 2009. The idea germinated during Terry’s visit to the Action/Abstraction exhibition at the Jewish Museum in New York in 2008, when he decided to spend a full hour with Hans Hofmann’s painting Fantasia (1943). “At the end of the hour, I was energised,” he remembers. “These micro-experiences can be transformative and go much, much deeper than a quick look.”

Roni Horn's Water Double (2013-16) is at Glenstone Museum Photo: Ron Amstutz, courtesy Glenstone Museum, © 2018 Roni Horn;

Research has shown that museum visitors’ encounters with art are generally brief—an average viewing time of 28.6 seconds per work, according to a 2017 study by Jeffrey and Lisa Smith and Pablo Tinio at the Art Institute of Chicago. That time includes reading the label and, for “a large percentage of visitors”, taking selfies, they noted.

The Slow Art Day format developed by Terry and his team of volunteers invites the public to contemplate five works of art—as selected by the participating museums—for ten minutes each, and then gather afterwards to discuss their experiences. Among the 94 venues holding events this year on Saturday 6 April are Yorkshire Sculpture Park, the National Portrait Gallery of Australia and Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Arkansas.

Over the past decade, the Slow Art Day “community” has organised more than 1,500 events on every continent (including Antarctica), Terry says, leading to spin-off collaborations in Poland and Belgium, and crossover activities involving dance, music and meditation. The annual initiative is “an open-source idea”, he says, which eventually “might just disappear because we’ve reached our agenda to support and provoke museums to do this on their own”.

These micro-experiences can be transformative and go much, much deeper than a quick look

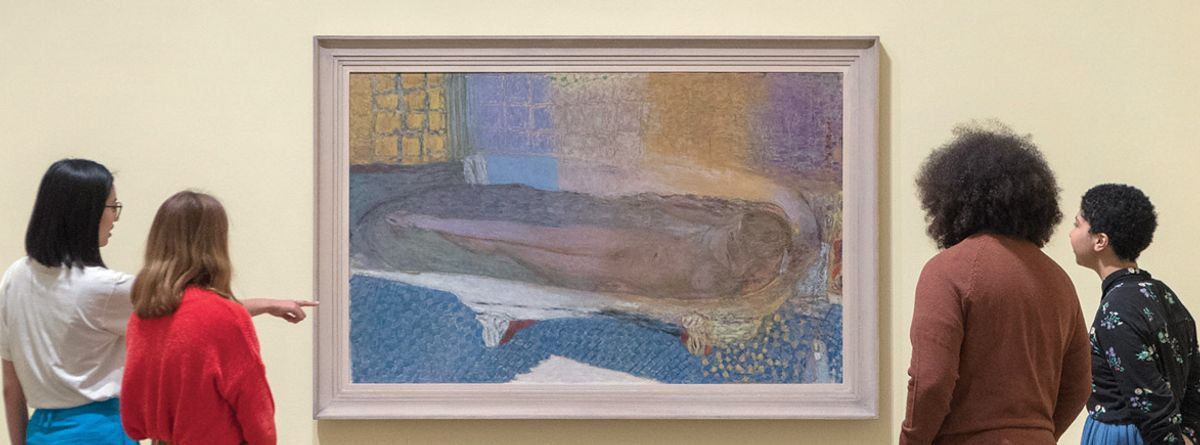

The Museum of Modern Art in New York, for example, has since 2016 hosted monthly ticketed “quiet mornings”, where people can explore the galleries at their leisure, followed by a guided meditation session. Encouraged by the “positive response” to its Slow Art Day event last year, Tate Modern introduced “slow looking” tours of the current Pierre Bonnard exhibition (until 6 May), a spokeswoman says, adding that the artist’s “complex colour palettes and unusual sense of composition especially reward close and extended scrutiny”.

For Rebecca Chamberlain, a psychology lecturer at Goldsmiths university, who led the London museum’s sold-out first tour last month, slow looking “intersects with ideas around mindfulness and wellbeing”. Chamberlain compares the process to “sensory mindfulness meditation”, where “your focus of attention is in the moment and not on external ideas or thoughts”, potentially alleviating anxiety. Potential health benefits aside, Terry argues that the format ultimately enables those with no art historical knowledge to build their “confidence and interest in looking”.

Tate’s tours, held after normal opening hours, are currently available to a maximum of 45 people. These contemplative conditions are naturally incompatible with most museums’ priorities to generate income and remain accessible to all, so what steps can an institution take to foster a Slow Art approach year-round?

Tate Modern introduced “slow looking” tours of its Pierre Bonnard exhibition © Photo: Tate

The look and feel of Glenstone, a private museum and sculpture park near Washington, DC, reflect the principle that a “calm, unhurried and spacious environment” yields “more meaningful experiences with art”, says its director and co-founder Emily Rales. The museum’s vast Pavilions expansion opened last October with sparsely hung galleries and a room dedicated to admiring the landscape outside. Only 400 timed tickets a day are available online, and indoor photography, through a smartphone or otherwise, is not permitted. So far, “demand has far exceeded expectations”, Rales says.

Even the Uffizi in Florence has introduced a raft of measures to improve—and prolong—the visitor experience. Reducing the hours-long queues at the entrance and easing bottlenecks around the gallery’s “most iconic pictures” have been “fundamental” priorities “since even before my first day in office”, says Eike Schmidt, the museum’s director since 2015. A judicious rehang of the Botticelli and Leonardo rooms “means that people automatically disperse better”, he says.

Seasonal ticket prices that are cheaper in the winter, as well as a new €70 surcharge for large groups, aim to discourage the whistle-stop, day-trip tours of high summer “that typically come in for 30 minutes”.

- For The Art Newspaper's full Art's Most Popular visitor figures survey, see our April issue. To read a selection online, see