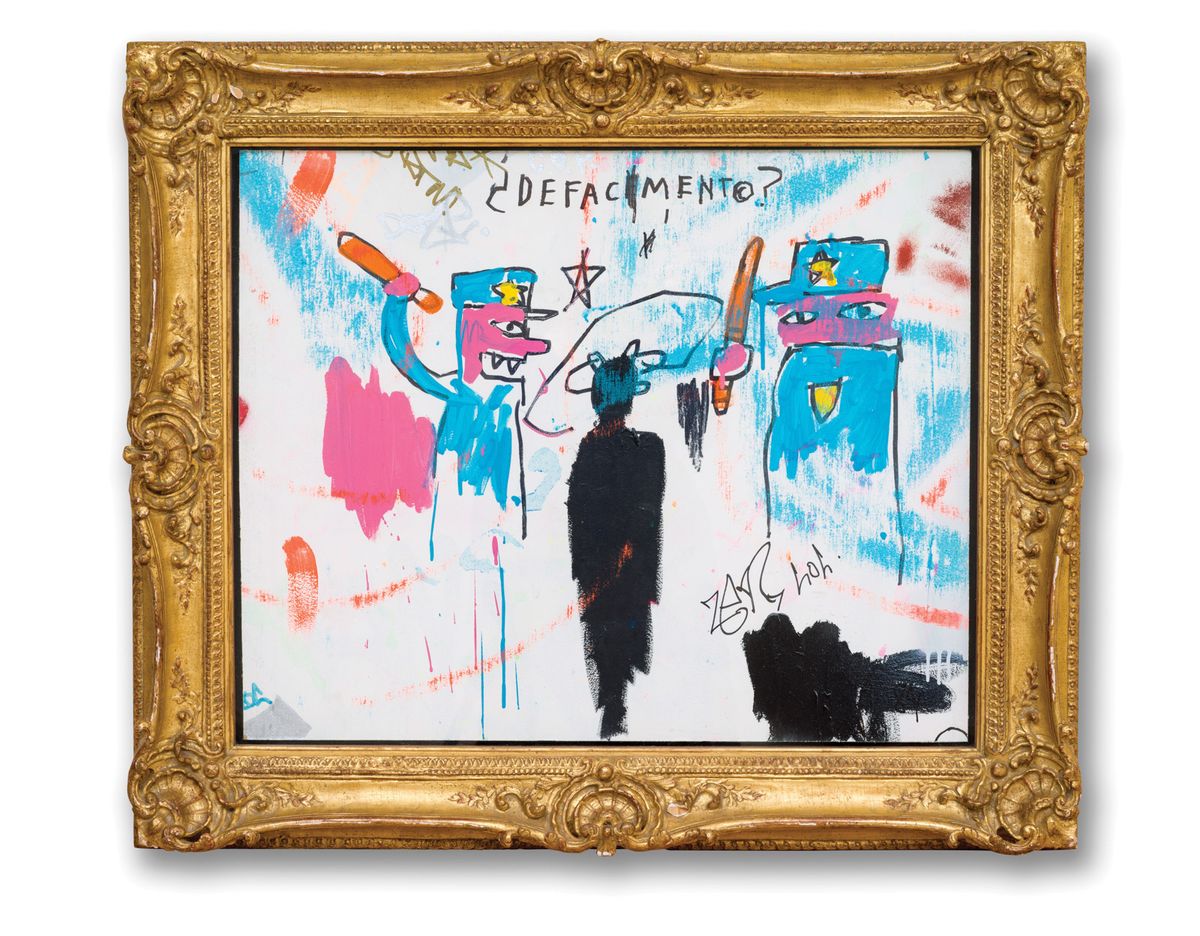

A painting by Jean-Michel Basquiat, created after his friend and fellow street artist Michael Stewart was beaten to death by New York City police in September 1983, is going on public display for the first time in Manhattan. Daubed directly onto the wall of Keith Haring’s Soho studio by Basquiat—who said at the time, “it could have been me”—Defacement (The Death of Michael Stewart) (1983) is the centrepiece of an exhibition at the Guggenheim Museum in New York (21 June-6 November).

The work is just as poignant today, at a time when police brutality is again in the spotlight. “Defacement does not have definitive answers to the current political climate, but it is very powerful to see an artist who is speaking their truth in an unfiltered way,” says Chaédria LaBouvier, the first black female curator to oversee a Guggenheim show.

“Defacement stands as evidence of sorts,” LaBouvier adds, “even before legal proceedings had begun, that Jean-Michel felt that justice would not be served and the painting steps in as an alternative to the justice system”. Stewart was attacked in custody after allegedly tagging a wall in an East Village subway station. In 1985, an all-white jury acquitted all six of the transit police officers indicted in Stewart’s case.

According to new research, Basquiat is likely to have painted Defacement between 29 September and 5 October after seeing a poster for a rally protesting Stewart’s then “near-murder” in Union Square on 26 September. LaBouvier believes the poster could have been one made by the US activist and artist David Wojnarowicz. “We are going through the authentication channels, but having had a chance to speak with people, including Wojnarowicz’s first gallerist, it’s clear we have found something interesting which helps us better understand Defacement’s composition,” LaBouvier says.

The painting steps in as an alternative to the justice systemChaédria LaBouvier, curator

The poster will be shown in the exhibition alongside other works created in response to Stewart’s death by artists including Keith Haring, David Hammons, and Andy Warhol. Haring’s work, Michael Stewart—USA for Africa (1985) depicts a naked man being strangled by a pair of disembodied pink hands. Around a year earlier, he had cut Defacement from his studio wall and hung it over his bed in an elaborate, baroque-style frame. The work remained in Haring’s possession until he died in 1990, when it was given to Nina Clemente, Haring’s godchild and daughter of the Italian painter Francesco Clemente.

For the show catalogue, LaBouvier has interviewed people who were directly involved in the aftermath of Stewart’s death. They include Michael Warren, the Stewart family’s lawyer, and Peter Noel, who was the lead reporter for the New York Amsterdam News at the time.

The curator has even tracked down the person who leased studio space to Stewart, casting the young man in a new light. “This cements the fact that Michael thought of himself as an artist,” LaBouvier says. “It makes it clear why so many East Village artists made works in response to his death. Michael Stewart was a member of their community.”