An ongoing Italian investigation into a group of alleged fakes by the late Italian artist Gino De Dominicis has all but paralysed the artist’s market, some dealers say.

The inquiry has so far led to two arrests and the seizure of around 250 works from the foundation which purportedly safeguards the artist’s legacy.

“We are in limbo,” says Claudio Poleschi, who runs a gallery in Lucca, Tuscany. Works by De Dominicis are now “nearly impossible to sell”, he says, adding that one of his collectors is trying to dispose of two large paintings by the artist, exhibited at the Venice Biennale during De Dominicis’s lifetime, but which have attracted little interest despite their solid provenance.

The veteran Italian dealer Massimo Minini concurs. “The artist is too hot right now; it’s difficult to sell [his art],” he says.

The issue came to a head in November when the Carabinieri’s art squad announced the arrest of two people connected to the Gino De Dominicis Foundation and Archive and the seizure of 250 “forged” works, some of which had been sold to “unwitting collectors”.

A total of 23 people are under investigation, the Carabinieri say, for alleged involvement in criminal association and forgery, and a number of them for having allegedly placed on the market “numerous fake works… with fraudulent certificates of authenticity”.

One of those reportedly under investigation is the politician and art historian Vittorio Sgarbi, a former minister of culture who was re-elected as a member of parliament for the Forza Italia party last year and also serves as the mayor of Sutri, a town south of Rome.

Rival authenticators

In 2011, Sgarbi established the Gino De Dominicis Foundation and Archive after falling out with fellow members of the Gino De Dominicis Association, set up a few months after the artist’s death in 1998. After the departure of Sgarbi and others, the remaining members of the association set up a new organisation, the Gino De Dominicis Archive. Since then, the two rival bodies have co-existed, with both authenticating works by the late artist.

In an article published in the Italian newspaper Il Giornale, Sgarbi denied all the charges laid against him by the Carabinieri. “There is no [evidence] proving that I knew that the works by De Dominicis which I authenticated were fakes… I am convinced that there are no fakes by [the artist]”, he wrote, adding that as De Dominicis’s art appeals to “an extremely limited number of collectors, there is no [incentive] to forge his work”. It is also “essential” to guarantee art critics “absolute freedom” to express their opinions, he added.

The two people arrested in connection with the investigation are the alleged forger responsible for producing the supposed fakes and the vice-president of the Gino De Dominicis Foundation and Archive, Marta Massaioli, who once served as the artist’s assistant and was able to use “her profound knowledge of his painting techniques and conceptual language” to forge his works, according to the Carabinieri.

Massaioli’s lawyer, Angelo Franceschetti, tells The Art Newspaper that he is unable to rebut specific charges against his client because the evidence in the case has not yet been disclosed by investigators. However, he says that Massaioli inherited 167 works from De Dominicis and that she is in possession of a will, handwritten and signed by the artist, bequeathing the art to her. This document has been authenticated by “numerous experts”, Franceschetti says.

A date for the first hearing in the De Dominicis case has not yet been set.

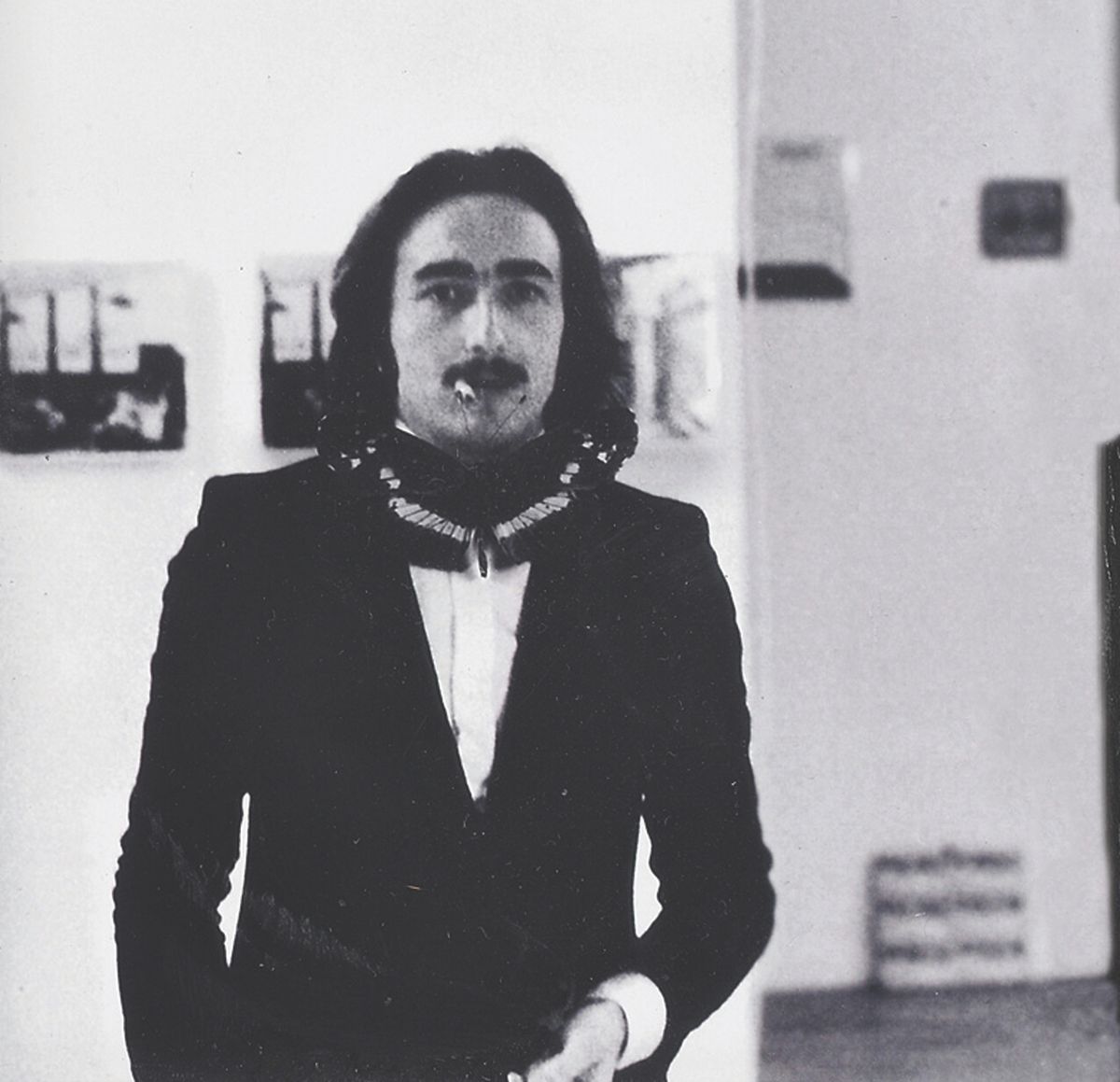

Artist, prankster and provocateur

Gino De Dominicis (1947-88) was a conceptual artist, painter, provocateur and prankster. He was a highly original creator, obsessed with metaphysical questions such as immortality, and he declined to associate himself with any of the leading art movements of his time. He once sold an invisible cube to a collector, and his installation piece for the 1972 Venice Biennale—Second Solution of Immortality: the Universe is Motionless, which consisted of a man with Down’s Syndrome sitting motionless on a chair and gazing at a stone, a sphere and an imaginary cube—was shut down after only a few hours following widespread condemnation.

Small market

De Dominicis’s disdain for the art market and for cataloguing his own work has made the study of his work challenging. Mariolina Bassetti, the head of Modern and contemporary art at Christie’s Italy, says: “The artist did not actively contribute towards an historical archive of his works… The largest historic exhibition [of his work] was realised after his death, so there is very little study… around his oeuvre… Following his death, it proved even more difficult to source the information necessary to historicise the artist, as there were no images or catalogues available for research. It is very rare for his works to appear on the market. In the last five years we have only seen about 30.”

The artist’s top price at auction is €270,000 for a 1990 graphite and tempera work on board—Untitled (staircase)—which was sold at the Italian auction house Farsettiarte in 2014, but dealers say his work has changed hands for much more privately.

The provenance of works is critical, Bassetti says: “The works that arrive to us… always come with excellent provenance and it is precisely this historicised trace which makes the works more precious.”

If the current investigation in Italy leads to criminal charges and a trial, then the case and any subsequent appeals could last years. “I’ll be dead by the time it’s over,” laments the dealer Claudio Poleschi, who says that confidence in the artist’s market is now so low that one collector recently asked to return a De Dominicis painting to his gallery and exchange it for a work by the Arte Povera artist Mario Merz.

Meanwhile, exhibitions of the artist’s work will need unimpeachable provenance. In 2017, Luxembourg & Dayan in London staged a show of his work that was drawn entirely from the collection of his friend and patron Guntis Brands. “Provenance and research about the works are key and often could tilt a collector or a dealer to make a decision to buy one work over another,” says Alma Luxembourg, a partner in the gallery and the founder of its London branch.