It is well-documented that works of art by women sell for around 50% less than those by men at auction globally, but new research reveals inequality in the gallery sector too.

Speaking on a panel about female artists at the Talking Galleries symposium in Barcelona on 21 January, the economist Clare McAndrew exposed how the more established a woman becomes, the less likely she is to find gallery representation.

If being established is defined as having an auction record, McAndrew found that women accounted for just 16% of the established artists from the 3,050 galleries on Artsy's database. That figure rises to 36% for “unestablished” female artists—defined here as those whose work has never been sold at auction.

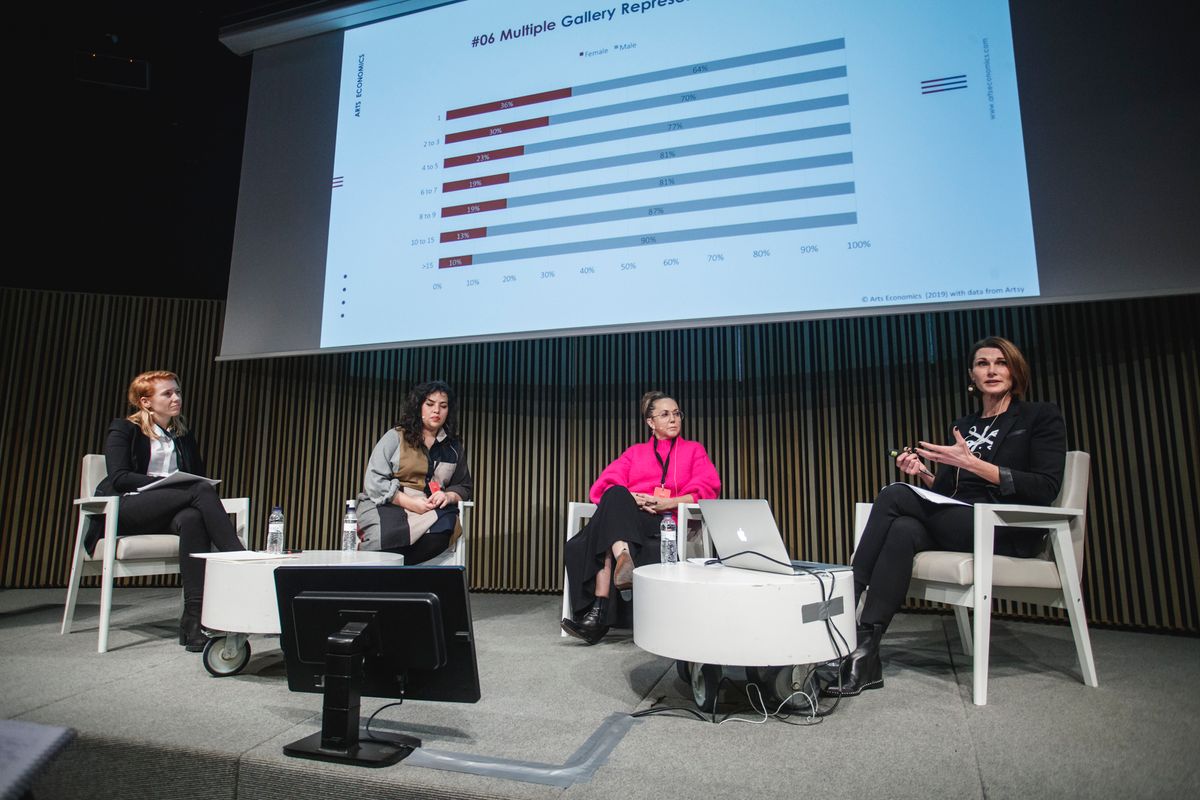

Further evidence of the widening gap higher up the ladder is that while 35% of artists who are represented by just one gallery are female, of the artists who are represented by nine or ten galleries, less than 10% are women. “You can pretty much equate wider representation with success, hence women are less represented or successful as a whole group,” says McAndrew, whose full findings are due to be published in the Art Basel and UBS Global Art Market Report, out in early March.

Another inquiry using the same database makes for equally depressing reading. As much as 10% of galleries have no women on their books at all, while only 8% represent more women than men. Almost half (48%) represent 25% or fewer women. Meanwhile, in a study of 820,000 exhibitions across the public and commercial sectors in 2018, only one third are by female artists.

McAndrew suggests that there are sociological reasons why women are undervalued and under-represented in the market. This is partly due to the “normal” discrimination and cultural biases we see across most, if not all, industries. “Gatekeepers–museums, galleries, curators, media and collectors–discriminate against women for some reason,” she says. “So, when men and women produce the same thing, women get paid less.”

Equally, McAndrew says there is the potential for “socially constructed, not biological differences” in male and female works. “We need to at least ask the questions: do we tend to value male attributes more and are artists judged as good or bad within a traditional male framework for success?” she asks.

Peter Gerdman, the head of research at ArtTactic, offered a glimmer of hope, however. Speaking on a panel on the African art market at Talking Galleries on 22 January, his data showed that three out of the top five selling African artists at auction are women–and they are all alive. Marlene Dumas tops the list, followed by Njideka Akunyili Crosby. Julie Mehretu comes in at fourth.

This compares with all top five spots being occupied by men in the UK and US auction markets, nine of them white and seven of them dead.