Warhol or a Wool hanging on your wall may give you great pleasure, but it used to be that art gave you no monetary return—unless you sold it.

No longer. Today that work of art can remain on your wall and at the same time give you cash in hand, allowing you to buy more art, inject some money into your business, cover a guarantee at auction or pay off an urgent tax demand.

Borrowing against art poses specific problems because of its portability, its heterogeneous nature and difficulty in establishing a reliable price. And yet, according to a report published last year by Deloitte and ArtTactic, in 2017 the global total of loans outstanding against art was eye-popping: between $17bn and $20bn.

“Perhaps the biggest driver of growth in this field has been a mindset shift by collectors who once viewed their art purely as a hobby or aesthetic pursuit and now view it as a strategic asset,” writes Evan Beard, a national art services executive at US Trust, in the first Tefaf Art Finance Report, published earlier this year. US Trust has a stunning $6.7bn out in loans secured against art, and other private banks such as Citi or JP Morgan have loan books that also run into the billions of dollars.

“You will probably find that many of the US-based names in Artnews’s top 200 collectors list have borrowed against their art holdings,” Beard says.

While precise figures are difficult to obtain, according to a number of players in the market the vast bulk—in excess of 80%—of the art-secured lending business is in the US.

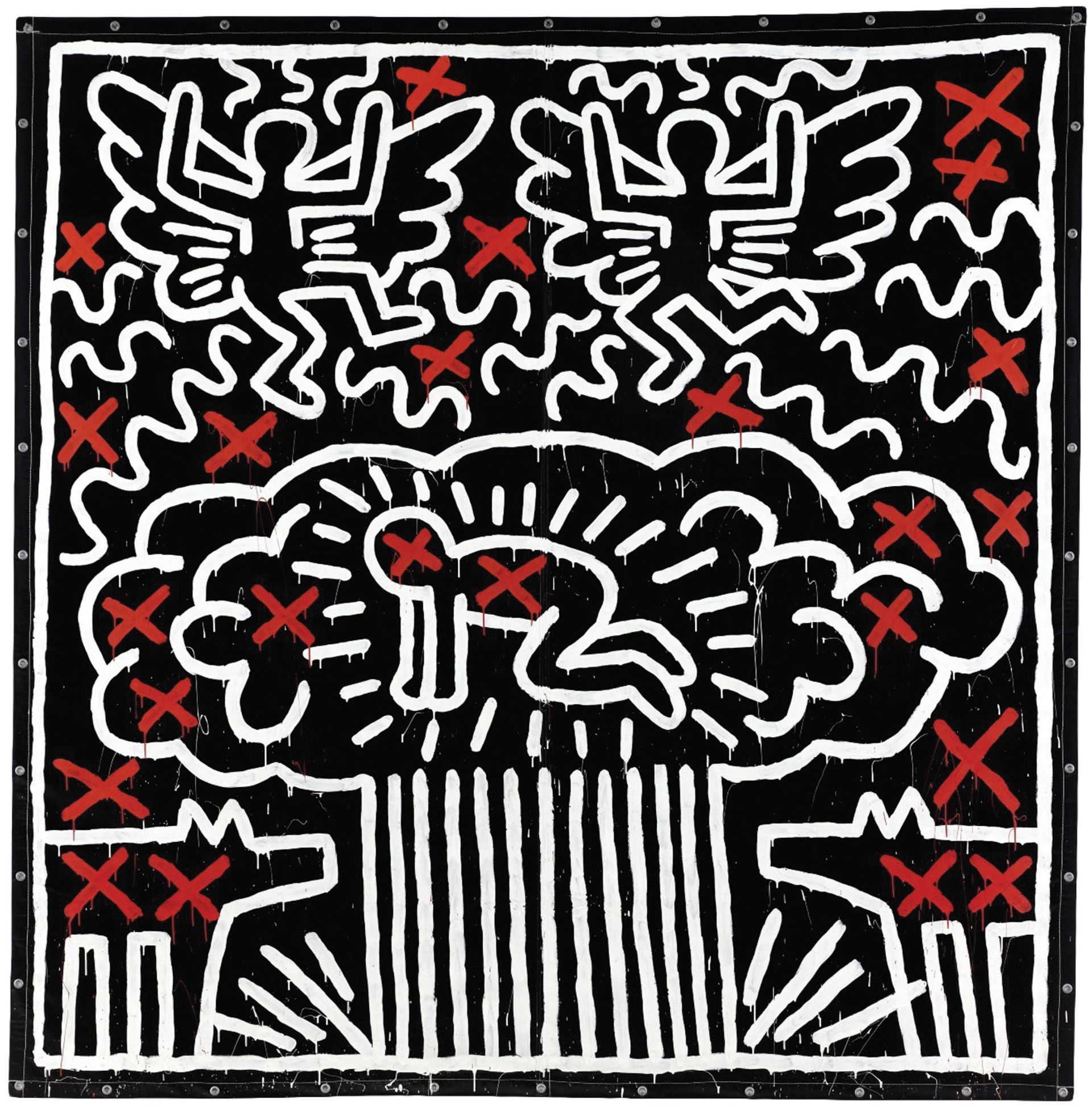

Keith Haring's Untitled (1982) © 2018 The Keith Haring Foundation. Courtesy of Sotheby’s

And it is a buoyant sector: “Our client base in the US is strong and growing,” says Suzanne Gyorgy, the head of Citi Private Bank’s Art Advisory and Finance. “Most notable is the increase in the size of the art loans. Ten to 15 years ago, typical art loan facilities were in the tens of millions; today it’s increasingly common to offer art loans facilities in the hundreds of millions.” And while the US is strong, Gyorgy says, “Business is growing dramatically in Asia and Latin America as well.”

“Americans are so much more accustomed to borrowing,” says Barbara Chu, a partner at Emigrant Fine Art Finance, the art lending arm of Emigrant Bank: “And there are cultural biases against borrowing in some countries; people are generally averse to debt in the UK and Germany.” She adds: “Our financing offers another option for people to monetise their offshore assets.”

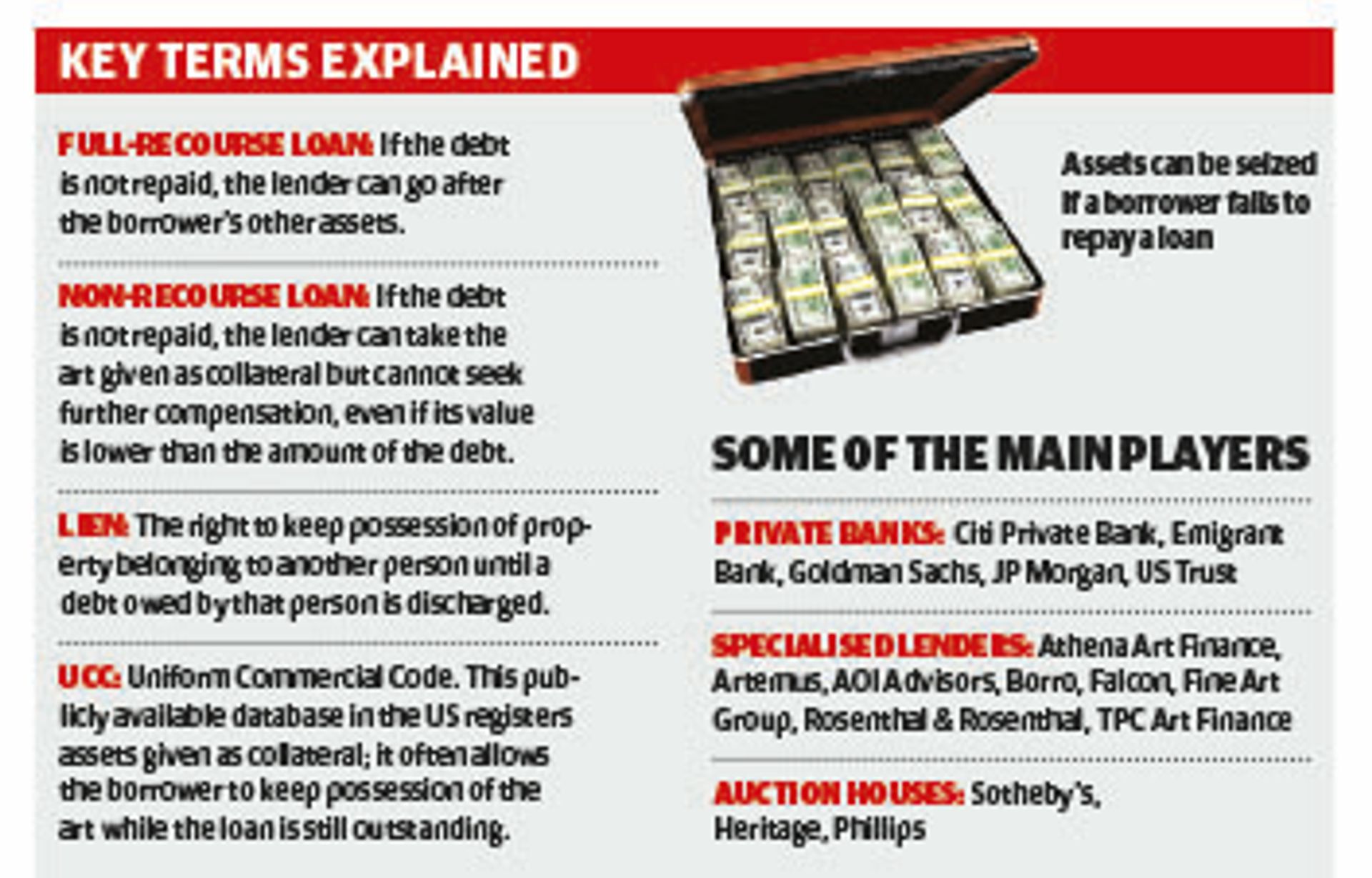

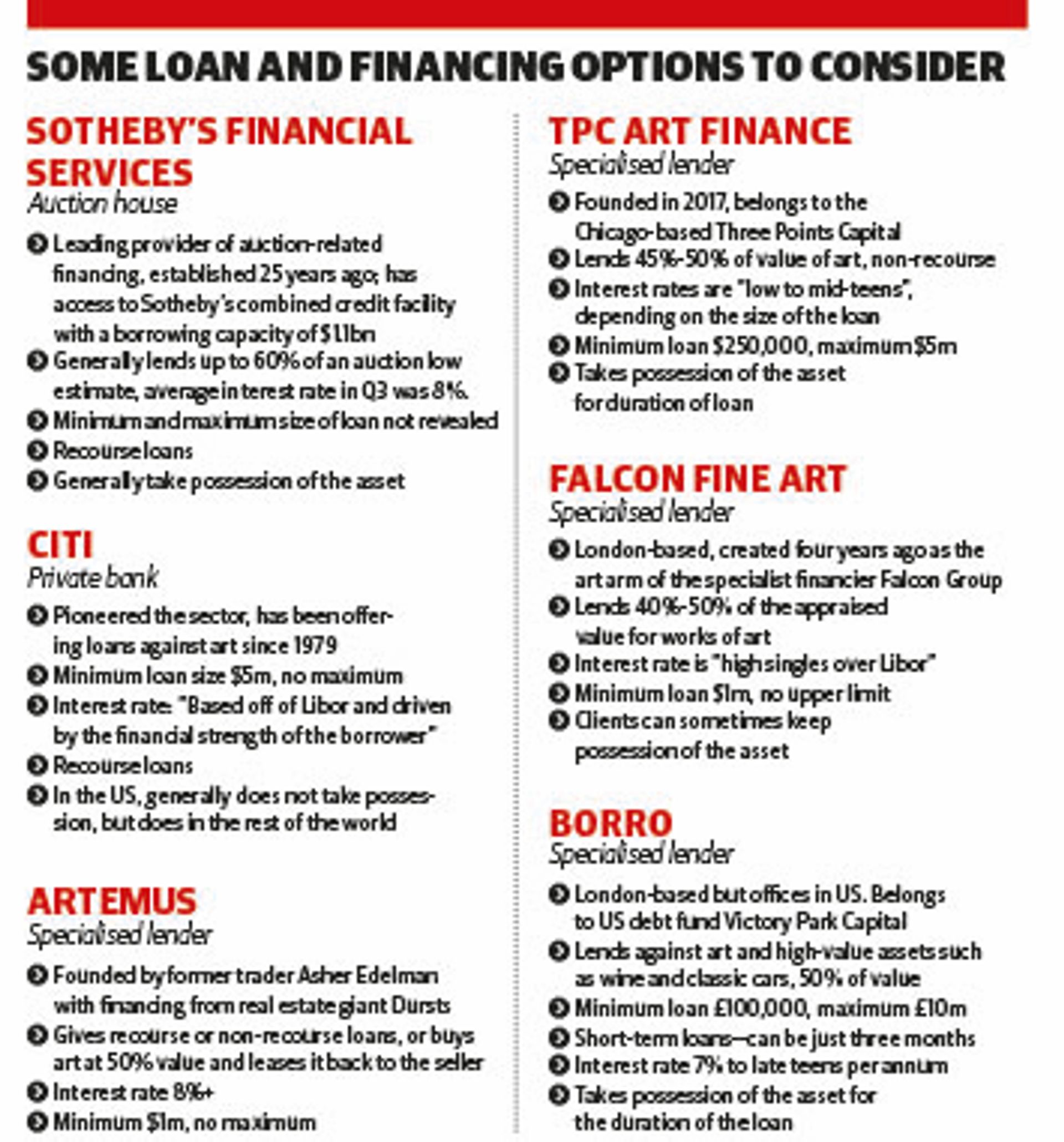

The biggest loan books are held by private banks, such as US Trust, with departments servicing their clients by giving recourse loans against their art holdings. But for others, there are specialist boutique lenders offering both recourse and non-recourse loans, and here is where there are a number of newcomers in the field: the London-based Fine Art Group moved into this area two years ago, TPC Art Finance just one year ago. The auction houses are also more than willing to lend against art and the main player, Sotheby’s, has a $1.1bn war chest with which to do so.

Almost all of the firms will lend against 40% to 50% of the appraised value of the artwork; some will take possession, others not. In the US, Uniform Commercial Code (UCC) filings identify works of art with a lien against them, and in many cases this means that the borrower can continue to enjoy their artwork and not see it crated off into storage. Elsewhere in the world, where no UCC exists, lenders generally want to hold the art until the loan is paid off.

UCC filings are publicly available, and a quick browse through some of the lenders reveals a wide spread of owners who have leveraged works. The Turkish trader Yomi Rodrik, for example, has borrowed against nine works by the likes of Rudolf Stingel, Anselm Kiefer, Takashi Murakami and Jean Dubuffet from Athena Fine Art Financing, launched three years ago by Carlyle Group with $280m in funding (but now seeking a buyer). Omanut Holdings borrowed against 25 works, including Keith Haring, Mark Grotjahn and KAWS, from TPC Art Finance. Art dealers who have taken loans—among them Pace, Mitchell-Innes and Nash, Kasmin and Gagosian—can also be found in the filings.

Interest rates vary wildly depending on a number of factors. At one end of the spectrum are the private banks, who can offer very favourable rates—from the mid-single figures—to their clients, who have other assets beside art; some will only lend over $5m, with a minimum term for at least a year. And remember that a $5m loan means the work of art must be worth at least double that. Most lenders, as well, prefer to lend against a collection rather than a single piece.

Then there are the specialised lenders, who are likely to charge interest in the upper single figures; some, such as TPC, Falcon Fine Art, are the lending arm of a bank or finance company. “Non-banks” such as Sotheby’s will lend up to 60% of the low auction value at around 8% interest, but generally will do so against future consignment of the work(s) for sale.

At the other end of the scale are short-term, lower-value lenders such as Borro Private Finance, with offices in London, New York and Los Angeles, which might give a loan for just £100,000 for three months, but at 1% to 2.5% interest per month.

Outside the US, according to Dr Tim Hunter of Falcon, “the market is massively underdeveloped”. He identifies a number of reasons: the absence of UCC, the varying laws in different countries and cultural differences. But things are changing, says Freya Stewart of the Fine Art Group, which lends in the $500,000 to $150m range: “In Europe, younger collectors have a different view of the concept of leveraging assets; they are far savvier than the older generation and see this as a smart thing to do.” However, some borrowers may be entering too enthusiastically into loan agreements. This year there have been cases of overleveraging, for example the US art dealer Anatole Shagalov, who has taken loans against art but has allegedly defaulted on some purchases. An outlier, perhaps, but the consequence of what some see as a very frothy art market.