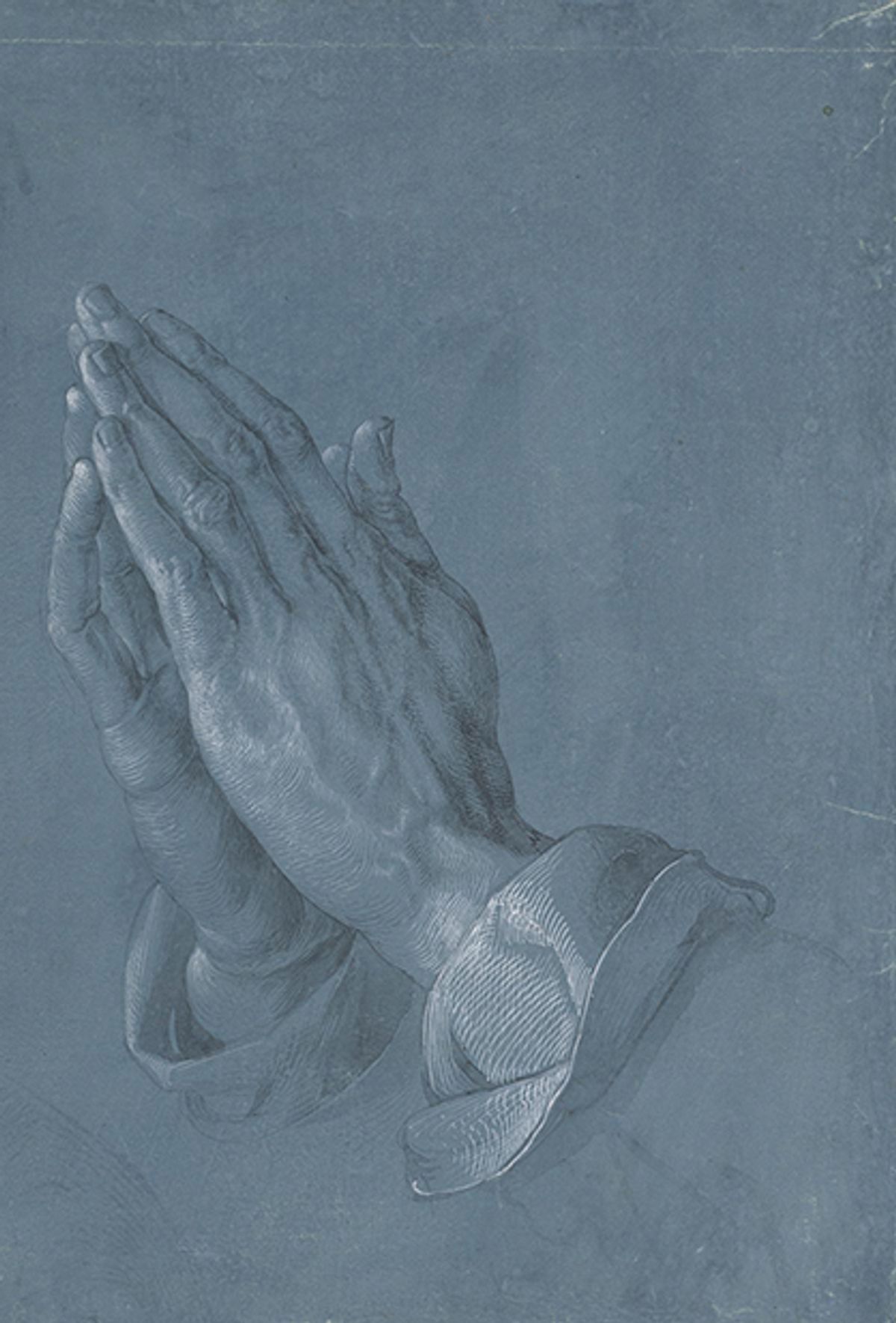

Albrecht Dürer’s Praying Hands (1508) was not, as has been assumed for centuries, a preparatory drawing for a painted altarpiece, but a finished work made as an advertisement for the master’s talent. This revolutionary theory will be put forward by the chief curator of Vienna’s Albertina in a major Dürer exhibition late next year (Albrecht Dürer, 20 September 2019-6 January 2020).

The Albertina’s Christof Metzger also argues that the drawing depicts the actual hands of the artist. If so, this raises intriguing physiological questions about the hands of the greatest artist of the northern Renaissance.

Praying Hands is now among the most famous drawings of all time. Metzger suggests that it is more widely recognised than any other, with the possible exception of Leonardo’s Vitruvian Man (around 1490). More than five centuries later, reproductions of the work still adorn the homes of millions of people, as a religious icon.

Since the 19th century, it has been assumed that the work was made as a study for an apostle in the lower-right corner of the central panel of the Heller altarpiece (completed 1509), named after the Frankfurt merchant who ordered it. The original panel was destroyed by fire in 1729, but a good copy by Jobst Harrich survives and is now at the Historisches Museum in Frankfurt.

Art historians have always believed that Praying Hands was a preliminary study for the altarpiece. This argument was put forward most recently in two important exhibitions in 2013: at Frankfurt’s Städel Museum and the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC (where the catalogue entry was written by Heinz Widauer, Metzger’s curatorial colleague at the Albertina).

Metzger says that scholars are wrong: he asks why Dürer would have gone to the trouble of making a highly finished drawing only for it to be scaled down for a tiny detail in a painted altarpiece.

“The work represents a miracle of observation and it is too ambitious to be merely a preliminary study,” he says. “Dürer made it as a ‘master drawing’ to show to visitors in his workshop, as an example of his God-given talent.”

According to Metzger, Praying Hands and a few other associated drawings were produced “to advertise Dürer’s talents”. They would have been brought out to show a range of prospective clients the quality they could expect from a commission from the artist.

He also argues that the drawing depicts Dürer’s own hands. “The very delicate fingers and hands are reminiscent of those in the 1500 Munich self-portrait. The little finger of the partially hidden hand on the left in the drawing seems to have a curvature or stiffening of the joint, which appears in other self-portraits, such as the 1493 drawing at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art.”