Who is a great artist? Who is not? It is usually time alone that provides an answer to these questions. It separates the wheat from the chaff. Some artists go in and out of fashion (Michelangelo in the 18th century); others are obscure until much later "discoveries" (Vermeer in the mid-19th century). Some are well received in their lifetimes, only to disappear until a revival. Pieter Bruegel the Elder (around 1525/30-69) was one of these.

At first hailed as the “second Bosch”, from the 17th to the 19th century there was little appreciation or understanding of his work. (In the 18th century, his son Jan I, one of Rubens's collaborators, was the favoured member of the family.) Where his work was known, it was for his "droleries": depictions of oafish, peasant life—The Peasant Wedding (around 1567)—to the extent that he was given the title of "Peasant Bruegel".

Only from the beginning of the 20th century did his work begin to be taken seriously, his oeuvre established, and a more accurate appreciation of his drawing and painting came into focus. Now, on the 450th anniversary of his death, the Kunsthistorisches Museum (KHM), Vienna, presents Bruegel: the Master (until 13 January 2019). This is without a doubt the most complete exhibition of his 90 works to be seen for at least a generation. Simple figures—Bruegel by numbers—bear this out: on show are 30 of his 40 extant paintings, and half of his prints and drawings. Of course, Vienna is in a privileged position to achieve this result as the KHM itself holds 40% of paintings while its neighbour across the road, the Albertina, has 90% of his works on paper, most on loan.

To top up the harvest, exceptional works have also been loaned to the KHM from around the world. These include Haymaking (1565) from the Lobkowicz Collection in the Czech Republic, complementing the four KHM Months or Seasons (1565)—The Gloomy Day, The Harvesters, The Return of the Herd and Hunters in the Snow—Bruegel's only cycle, reassembled for the first time since its dispersal in the 19th century. Also loaned are The Bay of Naples (1562) from the Galleria Doria Pamphilij, Rome; Two Monkeys (1562) from the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin; The Triumph of Death (1562) from the Prado, Madrid; Dulle Griet (1562) from the Museum Mayer van de Berg, Antwerp; The Tower of Babel (1568, alongside, for comparison, the KHM's 1563 version) from the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam; The Adoration of the Magi in the Snow (1563) from the Oskar Reinhart "Am Römerholz" Collection, Winterthur; and The Adoration of the Magi (1564) from London's National Gallery.

The exhibition has an exceptional team of curators: Manfred Sellink, the director of the Royal Museum of Fine Arts, Antwerp, who has studied Bruegel over his entire career and is the author of the catalogue raisonné of drawings and paintings (2011); Elke Oberthaler, the KHM's head of painting conservation; and Alice Hoppe-Harnoncourt, a specialist in conservation and collection history. All three have been actively involved in the Bruegel Research Project which, since 2012, with the support of the Getty Foundation, has undertaken a comprehensive technological analysis of the KHM's Bruegel works. (Some paintings have been restored specially for the exhibition.) Other curators are Sabine Pénot, the KHM's curator of Netherlandish and Dutch paintings, and Ron Spronk, the Professor of Art History at Queen's University, Ontario, and at Radboud University, Nijmegen, who is a Bruegel expert.

All the curators have contributed to the catalogue (in English from Thames & Hudson and in German from Belser Verlag) that has as a special feature a link to a series of extra online essays. But, as Sellink is at pains to point out, this exhibition and its catalogue cannot be considered as the last word on Bruegel (Sellink himself changed his mind about authenticity of The Harbour of Naples, which he doubted in his catalogue and now deems to be autograph) but is a staging post—albeit a major one—of ongoing Bruegel studies. More on his production methods, for example, will be published online, while a symposium will be held in December on the subject.

Bruegel's biographical data are sketchy. He is thought to have been trained in Pieter Coecke van Aelst's studio in Antwerp and taught miniature painting by Coecke’s wife. He was admitted to the Antwerp painters' guild in 1551 and from 1552 to 1554 he travelled through France and Italy. He then worked briefly for the publisher, Hieronymus Cock, and from 1562 as an independent painter. The following year he established himself in Brussels where he died six years later. His oeuvre was relatively small, but his engravings of his paintings and drawings were widely disseminated by the 17th century. His principal innovations were in landscape and genre painting. At first hailed as a follower of Bosch, he has subsequently been interpreted as a humanist, moralist, satirist and social critic, as well as Christian apologist. No single aspect can be summary, but all are illuminating by turns. Hence the ongoing interpretative debates.

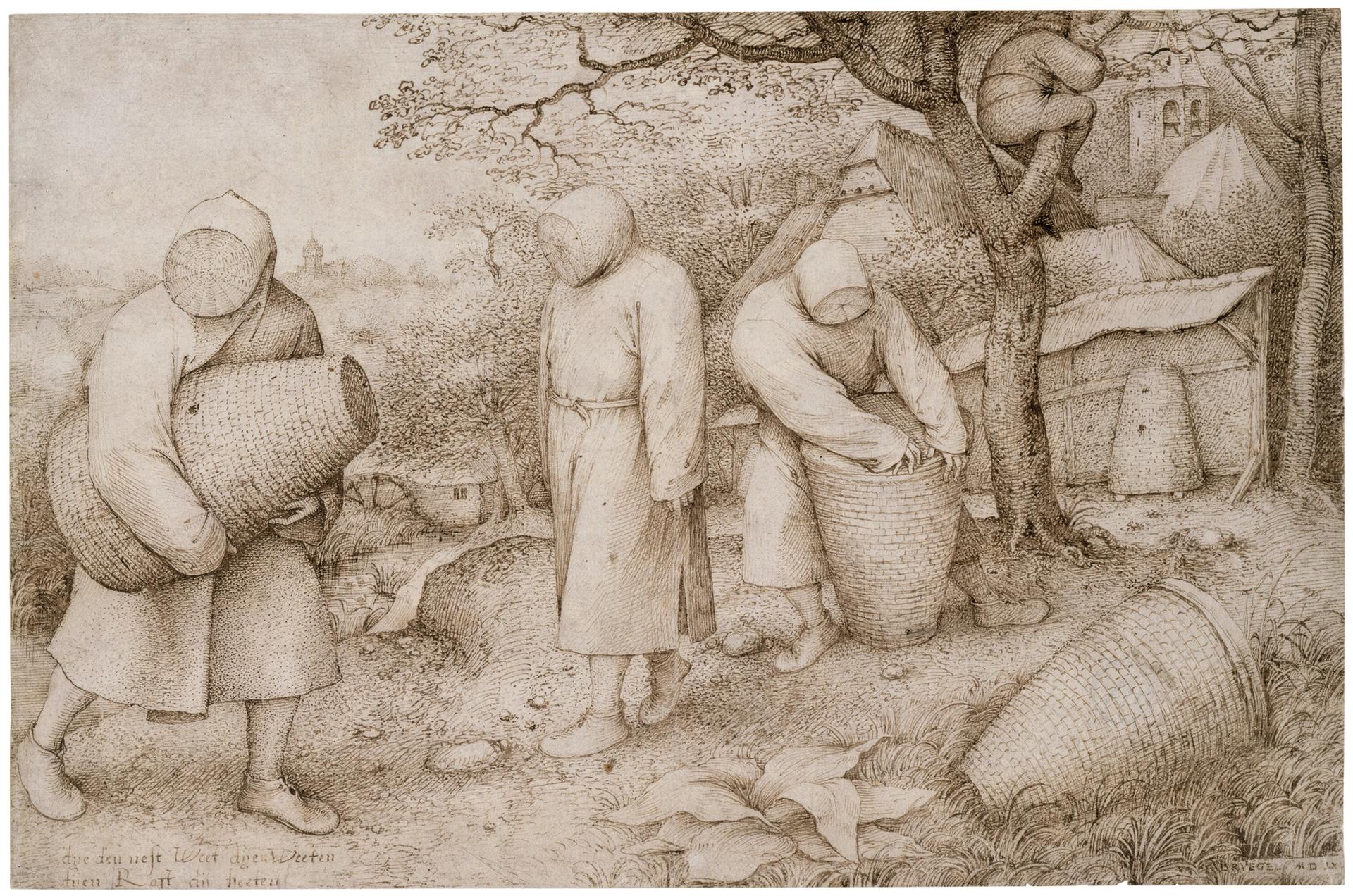

The KHM show includes the drawing The Beekeepers (around 1568) Photo: Jörg P. Anders; © Kupferstichkabinett der Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin ‒ Preußischer. Kulturbesitz

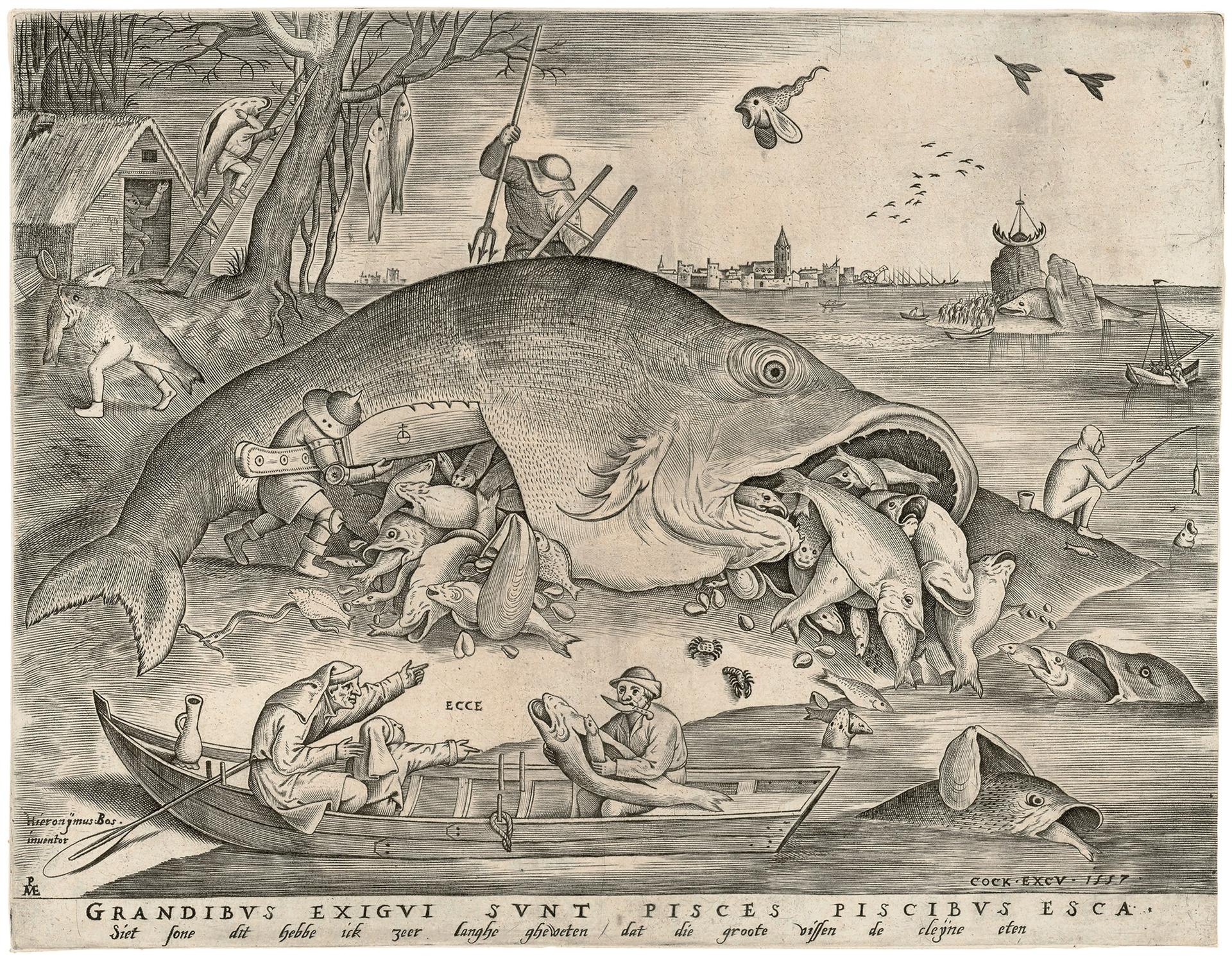

It would be tedious here to attempt to summarise the many insights that the exhibition and its catalogue afford of the many and varied aspects of Bruegel's work, not least allegories, emblems, riddles and questions (The Battle of Carnival and Lent (1559), Dulle Griet, Children's Games (1560), and the prints, Big Fish eats Little Fish (1556) and The Seven Deadly Sins (1557-58)), not to mention captivating and mysterious works such as the drawing, The Beekeepers (around 1568) and the eerie painting, The Magpie on the Gallows (1568).

Pieter van der Heyden after Pieter Bruegel the Elder, The big fish eats the little fish (1557) © Albertina, Vienna

Some of his religious subjects such as Christ Carrying the Cross (1564), The Conversion of Saul (1567), The Sermon of St John the Baptist (1566) or The Adoration of the Magi in the Snow are reminiscent of the Italian Mannerist trick of hiding the subject—Where's Wally?—in a huge landscape heavily populated by genre-like figures. Both his paintings and prints employ a range of unusual, but noteworthy, devices such as his tendency to show animals and people from behind, his careful arrangement of the direction of looks, his technical knowledge of ships and natural sciences, and his ability to capture the feel of snow and snowfall.

The works are broadly arranged in large galleries in chronological order with side rooms that are focused on particular details such as his tools, conservation discoveries and his work as miniaturist.

It is inconceivable that Bruegel will ever again be eclipsed and it is certain that this exhibition will be the first point of reference for years to come. It is literally a once-in-a-lifetime show.