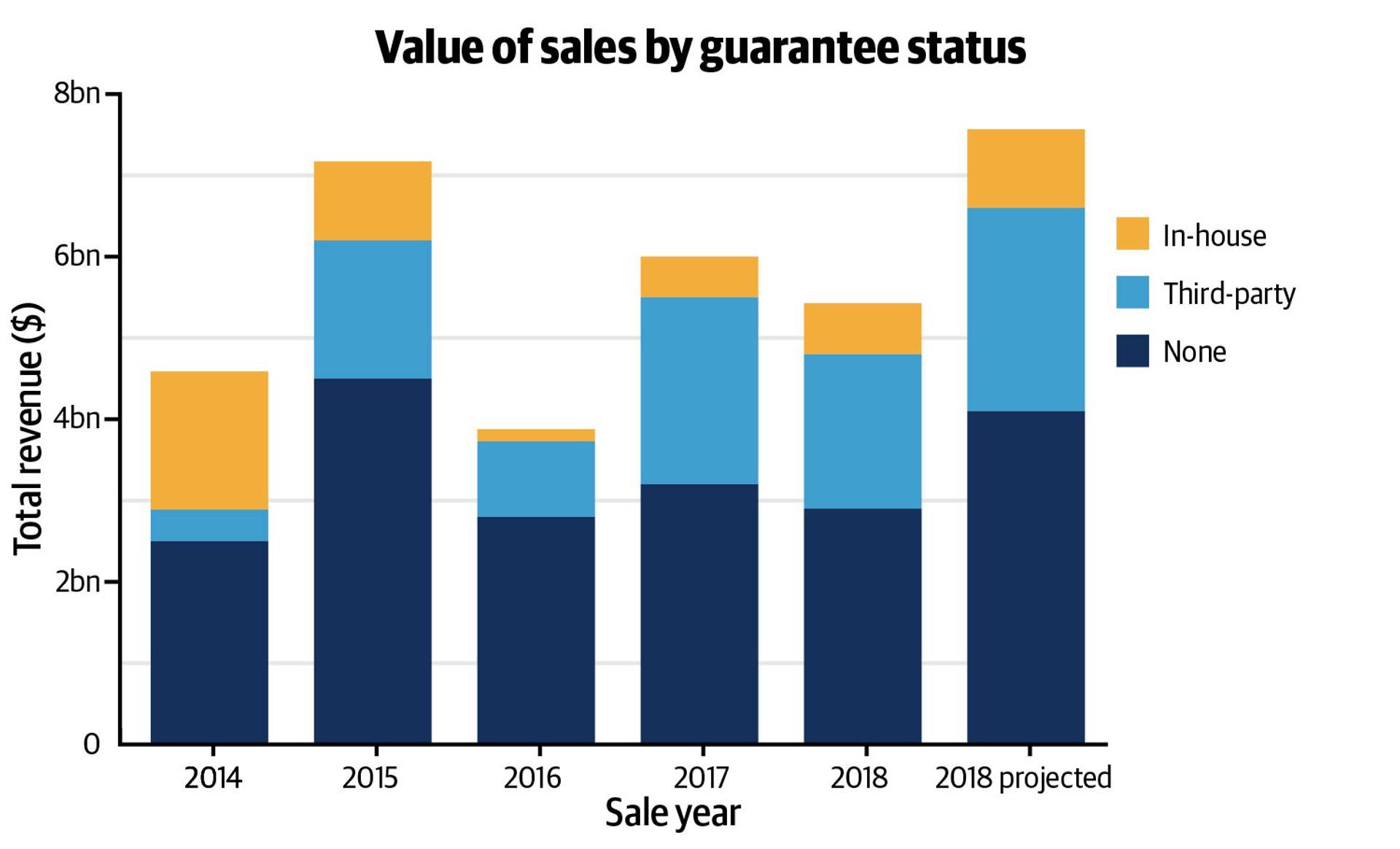

Third-party guarantees at auction—the art market’s hybrid of a risk hedge and a speculative gamble—are on track to hit an all-time high of around $2.5bn in 2018. On the face of it, guarantees offer a high level of certainty: the auction house secures a consignment and the seller receives a minimum price, whatever the outcome of the sale. But after the 2008 financial crisis, when sales tumbled and in-house guarantees forced auction houses to pay out large sums to consignors, they all but disappeared between 2008 and 2010.

Since then, auction houses have increasingly sought to offset this risk to third-party guarantors—individuals or consortiums that often have vested interests. Such deals are now the norm for high-value Impressionist, Modern and contemporary works. But experts warn that third-party guarantees, if misused, may precipitate a crisis.

“Guarantees have the potential to be the next big art-market scandal, if they are not carefully managed,” says Harry Smith, the executive chairman and managing director of the London-based art advisory firm Gurr Johns. “We seem to have one every 20 years, so maybe we’re due for another. And most crises come out of conflicts of interest.” Smith believes that third-party guarantees should come from a financial source without a “vested interest in the art market”, rather than being “passed around between a small club of guarantors, many of them with a direct interest”. The members of this club, he adds, are “often an auction house’s prime clients”, so the auction house is effectively negotiating a deal between two clients.

Guarantees increase liquidity by tempting people to buy and sell works when they do not need to, but they are also increasingly being used as a speculative, potentially lucrative financial mechanism. In the London sales during October’s Frieze week alone, the overall value of guarantees increased by 50% on last year, rising from an estimated £44.8m (from 32 lots) to £66.6m (49 lots), according to the analysis firm ArtTactic. Projections from one guarantor’s in-house analysis team estimate that auction sales worth $3.47bn worldwide in 2018 will have been covered by a guarantee, $2.5bn of those offset to a third party.

Follow the money

The extensive use of third-party guarantees is just one sign of the “increasing financialisation” of the art market, says Georgina Adam, editor-at-large of The Art Newspaper and the author of Dark Side of the Boom. “I do think it is worrying… they can reduce the work of art to a purely speculative instrument, and some of the third parties have no real interest in the art—added to which, the deals are hardly transparent.” Although auction houses “run a pretty clean ship”, according to Kenny Schachter, a collector, art dealer and journalist, he adds: “What’s pretty unregulated is what these idiots are doing in the room among themselves.”

Even before the financial crisis highlighted the risk of guarantees, Bonhams’ then-chairman Robert Brooks issued a public statement opposing guarantees in November 2007. “The minute an auction house moves away from simply being an intermediary between buyers and sellers and takes on the role of financier, it starts to change its core character as well as the relationship between the seller, his agent and the buyer,” he said. Brooks went as far as to say that the rising use of guarantees by some auction houses “ultimately erodes the credibility of the industry and thus its stability”. Bonhams has since changed its tune, and began to issue guarantees even before its acquisition by the private equity group Epiris in September.

Others believe that guarantees “distort the market and inflate prices”, says Rebecca Foden, a lawyer at the London firm Boodle Hatfield. Since third-party guarantors know the amounts and terms of the bids they have pledged, they are arguably in a better position than rival bidders, Foden says, which creates an “uneven playing field”. Becky Shaw, another lawyer at Boodle Hatfield, says that, although a third-party independent broker is an “appealing idea”, it is perhaps unlikely until there is demand for it by guarantors, or unless guarantees become subject to regulation.

One collector, who guarantees around four works a year for an amount “in the tens of millions”, says that funds would be better off protecting the masses than policing an elite market. “I think, in the art world, everyone deserves what they get. These are super-wealthy people playing a game largely fuelled by ego and their own conceit about how clever they are at trading in art.”

Increasingly sophisticated

Guarantees have become increasingly sophisticated. “Some of it is so convoluted that I have a hard time understanding the basic elements because there are so many variations of the guarantee,” Schachter says. These guarantees cannot be seen as formulaic because they relate to the motivations of buyers and sellers, and to market conditions, says Tom Mayou of the London-based advisory firm Beaumont Nathan. Adding to the confusion is the fact that the terms “irrevocable bid” (used by Sotheby’s) and “third-party guarantee” (Christie’s) are essentially the same thing, but are used interchangeably.

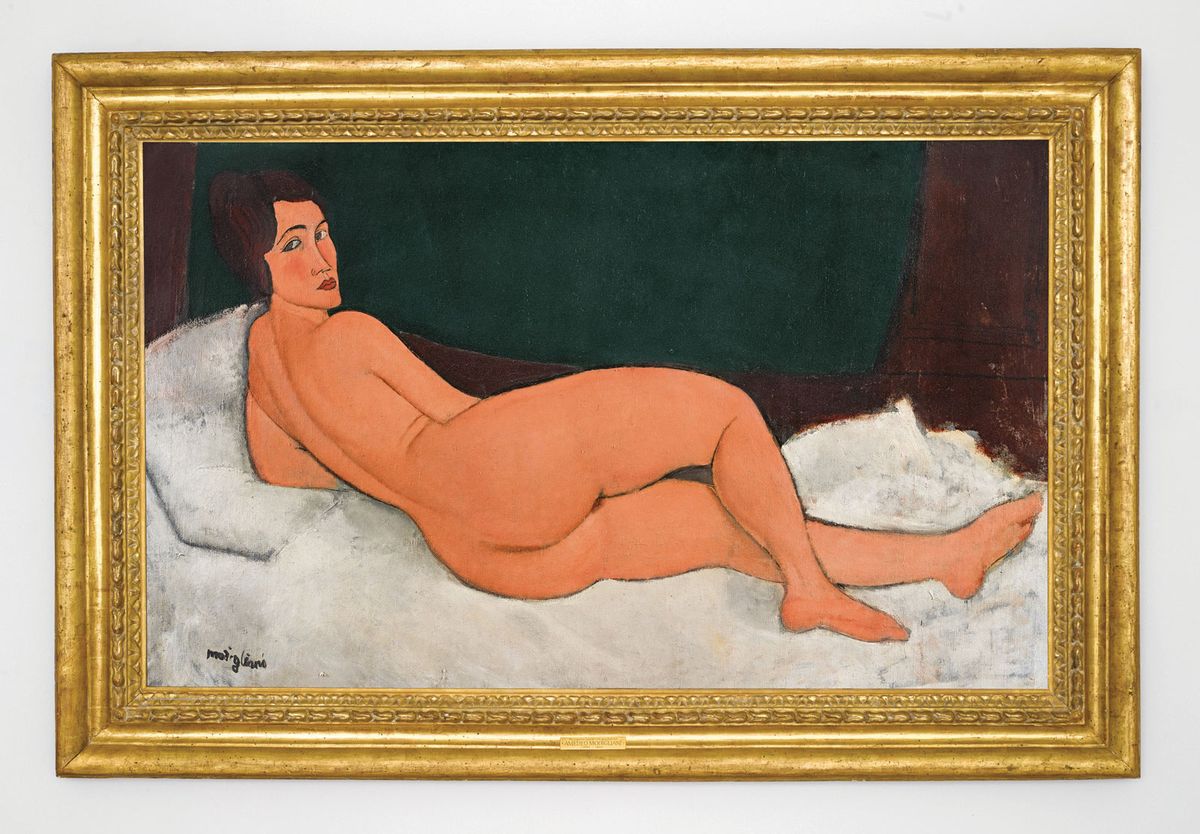

Schachter, who also guarantees works, says that there are “only a handful of people who guarantee works at $20m to $30m or more”. The Mugrabi and the Nahmad families are reportedly among them. It was the Nahmad family who apparently gave the highest ever third-party guarantee, at $150m, for Modigliani’s Nu couché (sur le côté gauche) (1917), which sold at Sotheby’s New York for $157.2m in May. So, as Schachter says, you have to know the market “because you’re up against the Mugrabis and the Nahmads… you can’t come in there foolhardy and think you’re going to walk away with a fat profit”.

The London-based dealer Inigo Philbrick offers around 20 to 25 third-party guarantees a year on works by artists such as Rudolf Stingel, Christopher Wool, Mike Kelley, Richard Prince and Wade Guyton. “For me, the best outcome of a guarantee is that you make a lot of money [without buying the work]. Say it’s a million dollars that you’ve risked, then you’d want to make $100,000 to $150,000 as your fee,” he says. “The second-best outcome is that you get a work you were happy to buy at a price you were happy to own it at. The second-worst outcome is that it sells on one bid and you make $5,000, having put in all this effort to negotiate a deal. [And] the worst outcome is the sort of guarantee you do purely for financial speculation and end up with a painting you don’t want to own.”

Data gathered by one guarantor’s in-house analysis team, from all auctions including guaranteed lots at Christie’s, Sotheby’s and Phillips, predicts that sales of lots covered by third-party guarantees will reach a high of $2.5bn by the end of 2018. So far this year, sales covered by third-parties have totalled around $1.9bn

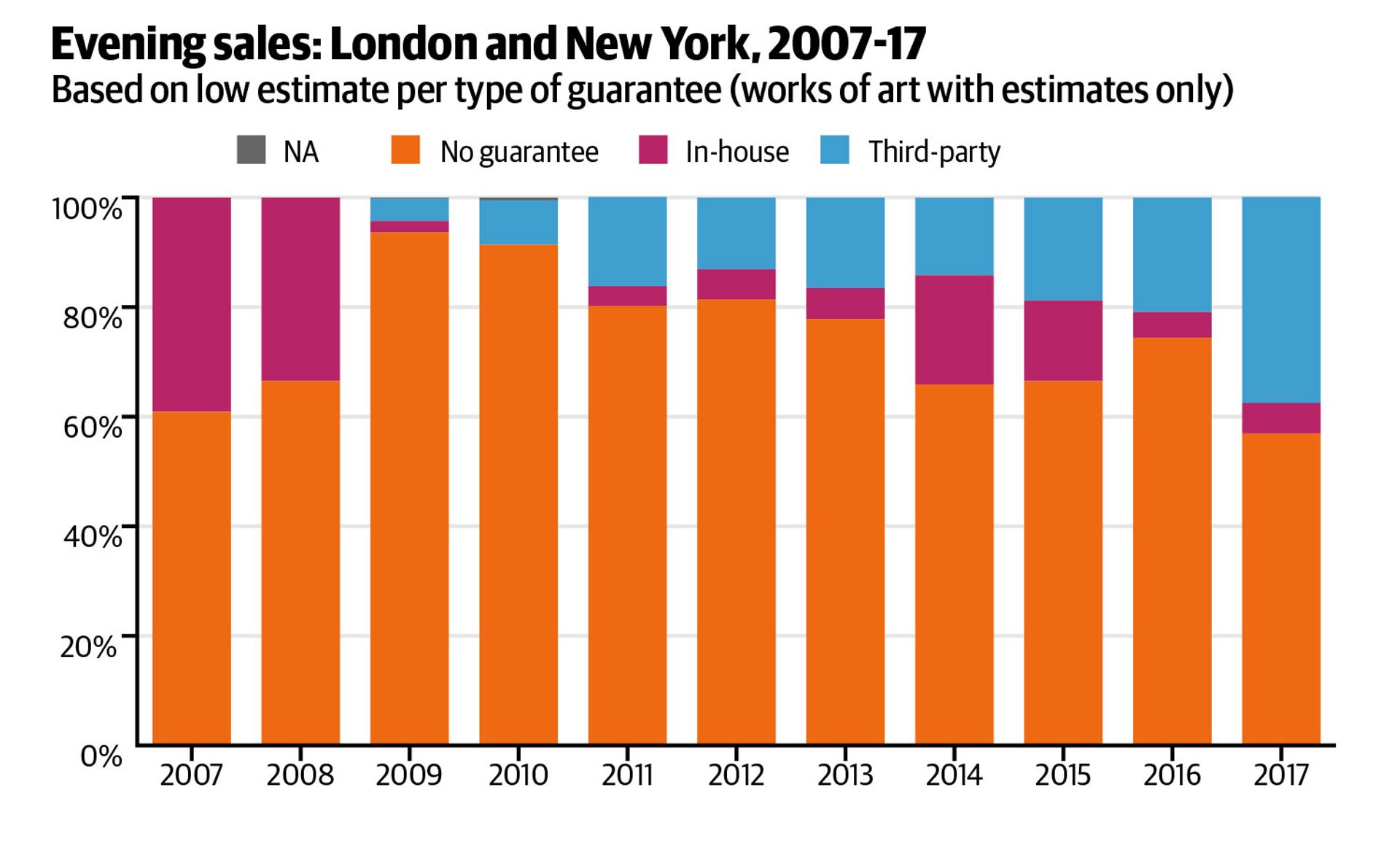

Pi-Ex’s data from Impressionist and Modern, and post-war and contemporary evening sales in London and New York over the past decade shows that although the number of in-house guarantees shrank dramatically following the financial crisis of 2008, works guaranteed by a third party have grown to 37% of total sales by value in 2017

The hedge-funders’ new Ferrari

Attracted by reports of high earnings, new third-party guarantors—many from financial backgrounds—are coming into the market, trading guarantees like futures. Speaking on ArtTactic’s podcast in September, Asher Edelman, the founding member and chief executive of the art-lending company Artemus, said that being a guarantor “is the hedge-funders’ new Ferrari”, and that he sees a “naïve crowd” of guarantors “doing pretty dumb transactions… and they’re gonna get stuck with them”. Doug Woodham, the former president of Christie’s for the Americas, also warns of the pitfalls of being a novice first part guarantor here.

Yet Adam Chinn, the chief operating officer at Sotheby’s, disagrees that guarantees are conflicting. “You may make the argument that there’s an inequality of information [between bidders], but I don’t think there’s a conflict of interest,” he says. Collectors today are more financially sophisticated, Chinn says, so “if I [the collector] want to buy object A, it makes sense for me to back object A, because if I don’t get it, I get paid, and if I do get it, I wanted to buy object A anyway”. Chinn believes that, in this way, guarantees have shifted from an almost wholesale market to being retail.

In the New York sales in May, around 65% of guarantors at Sotheby’s were private collectors (40% were first-timers), according to Chinn, while in November 2017, that proportion was 75%. Last year, 70% of lots backed by a third party sold above their irrevocable bid, so “you’ve got around a one-in-three chance of having to buy the property and around a two-in-three chance of getting paid”, Chinn says.

“Guarantees are like those ‘no money down, get rich quick’ ads,” Schachter says. “There’s no other speculative vehicle that affords you the upside with only having to pay in the case of a losing scenario.”

Imbalance of information

Last-minute third-party guarantees are also on the rise, with some clients waiting for a catalogue to arrive before combing it for lots to back. Such guarantees are announced in one quick burst just before an auction starts, which increases opacity, the dealer Nicholas Maclean of Eykyn Maclean says. This “rush of information at the beginning of the sale [is something that] many people miss”, he says. “They should be announced lot by lot.”

If a third-party guarantor buys a work, they receive a “financing fee” from the auction house and therefore pay less for the work than any competitors. Other bidders have no idea who is bidding on behalf of the third party—a bone of contention for Maclean, who suggests that “the auctioneer should be the one carrying out the bid for the guarantor, or it should be announced which member of staff is bidding on their behalf. It would be more transparent, particularly to new buyers unaware of the intricacies.”

“I think, in the art world, everyone deserves what they get. These are super-wealthy people”

He cites one problematic scenario. “If, hypothetically, a dealer sees a client who announces they’re going to bid on a painting, the next day the dealer could call the auction house and ask to guarantee it. The temptation might then be for the guarantor to get on the telephone and bid that person up.”

Auction houses put the onus on guarantors to disclose to their clients that they have a financial interest in a lot. But it is unclear whether this always happens, particularly when last-minute saleroom announcements make it impossible for bidders to question their advisers, says Doug Woodham, the managing partner of Art Fiduciary Advisors and the former president of Christie’s for the Americas. “For all they know, the person they asked to bid on their behalf may now have a financial interest in that very lot,” he says. Woodham suggests that collectors have formal agreements with their advisers to prevent this. “But unfortunately, there is no way for collectors to independently confirm their advisers’ actions because the identities of third-party guarantors are not disclosed by auction houses,” he says.

Possible solutions

New companies that could provide a solution to this regulatory gap are now entering the market. Christine Bourron, the chief executive of the art-market analysis firm Pi-Ex, has developed a financial instrument that enables investors to buy fractions of guarantees independently of auction houses—the first such product to be authorised by the UK’s Financial Conduct Authority (FCA). Aimed at institutional investors, a Contract on Future Sales (CFS) is standardised, like a futures contract, and therefore tradeable. “Professional investors can take a position on the future price of a painting; if they invest in 1% of a painting estimated at £1m, they will get 1% of the hammer price,” Bourron says. “We’re going to bring transparency and grow the fine-art market by opening it up to the financial markets.”

Pi-Ex’s guarantee product is yet to be fully launched for investors, and with so much power held in a small core of the market, it remains to be seen whether it will work in practice.

“Guarantees are like those ‘no money down, get rich quick’ ads”

Propping up the market?

Although guarantees have been the subject of criticism for inflating prices, it is hard to imagine returning to a market without them. “When you look at the performance of an artist, you cannot ignore whether or not some of his or her works were covered by third-party guarantees, because this is going to affect the prices,” Bourron says. “If you sell your work without a guarantee, you cannot expect to have the same performance.”

Schachter likens auctions with heavily guaranteed lots selling on one bid to the backer to “a dog and pony show… they’re bringing out these paintings that are, in effect, pre-transacted”. At a conference in April, Amy Cappellazzo, the chairman of fine art at Sotheby’s, seemed to suggest that auctions could become obsolete, because “by the time [the sale] happens, everything that was spontaneous and interesting has already happened”.

Manufacturing a new price level for an artist by giving an artificially high third-party guarantee is possible, but costly to maintain. “Manufacturing prices at auction is expensive; you have to pay a lot of money to the auction house,” Philbrick says. “The market is often too savvy for that. Just because one work sells for X amount, it doesn’t mean that everyone is going to start buying for that amount.”

Although it is currently dominant, the auction market for post-war and contemporary art is only around 20 years old. Only when those with vested interests in artists who regularly appear at auction with third-party guarantees (such as Basquiat, Warhol and Richter) retire or die, or when tastes inevitably change, will these multi-million prices be revealed as being built on firm foundations—or on stilts.

How auction guarantees work

Guarantees ensure that a work is pre-sold at a minimum amount, either backed by the auction house itself (house guarantee) or by a third party, who receives some of the upside should the work sell for more (typically 20%-30% of the overage above the guarantee, although this can be as low as 10% or as high as 50%). The more risk a third party takes on, the higher the potential reward.

- For more, see