Before the 18th century, art that was commissioned for private spaces would disappear the moment it passed from the hands of the artist to those of the owner. Collectors could then do with it what they liked. Some loaned works for public display, but that is more of a 19th- and 20th-century phenomenon. Most displayed the works in some personal setting, a bedroom wall or a sitting room, and so the object was no longer available to the wider world, aside from the intimates and invited guests of the owner. But these works were technically still “extant”, which in art history terms means that their location was accounted for. They could be in private homes or in Swiss bank vaults, but the same term is used, whether or not scholars or members of the public could visit the objects if they wished.

This has always struck me as odd. Think of all those works disappearing into private hands during next week's frenzy of auctions in New York. These are more “lost” in terms of access than “extant”. Perhaps a third term should be created to mean “extant but inaccessible?” Because while there is a moral pressure on buyers to keep works of art theoretically accessible at least to well-intentioned scholars, if not for occasional loan to public exhibitions, there is no legal obligation to maintain the work’s visibility, or indeed to keep it in good condition—even not to destroy it.

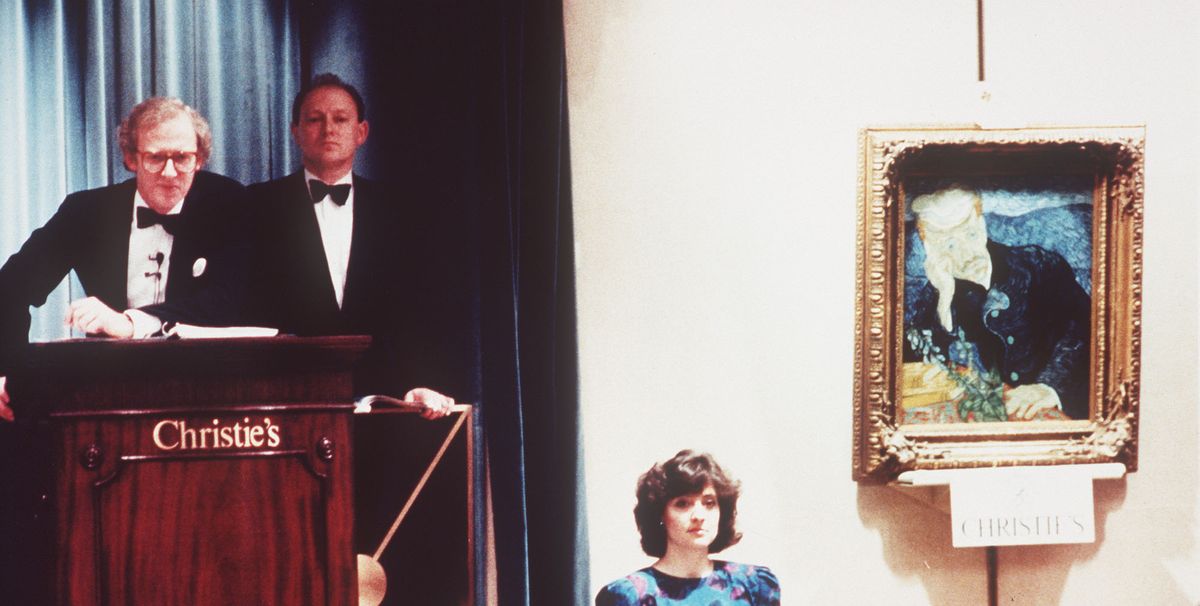

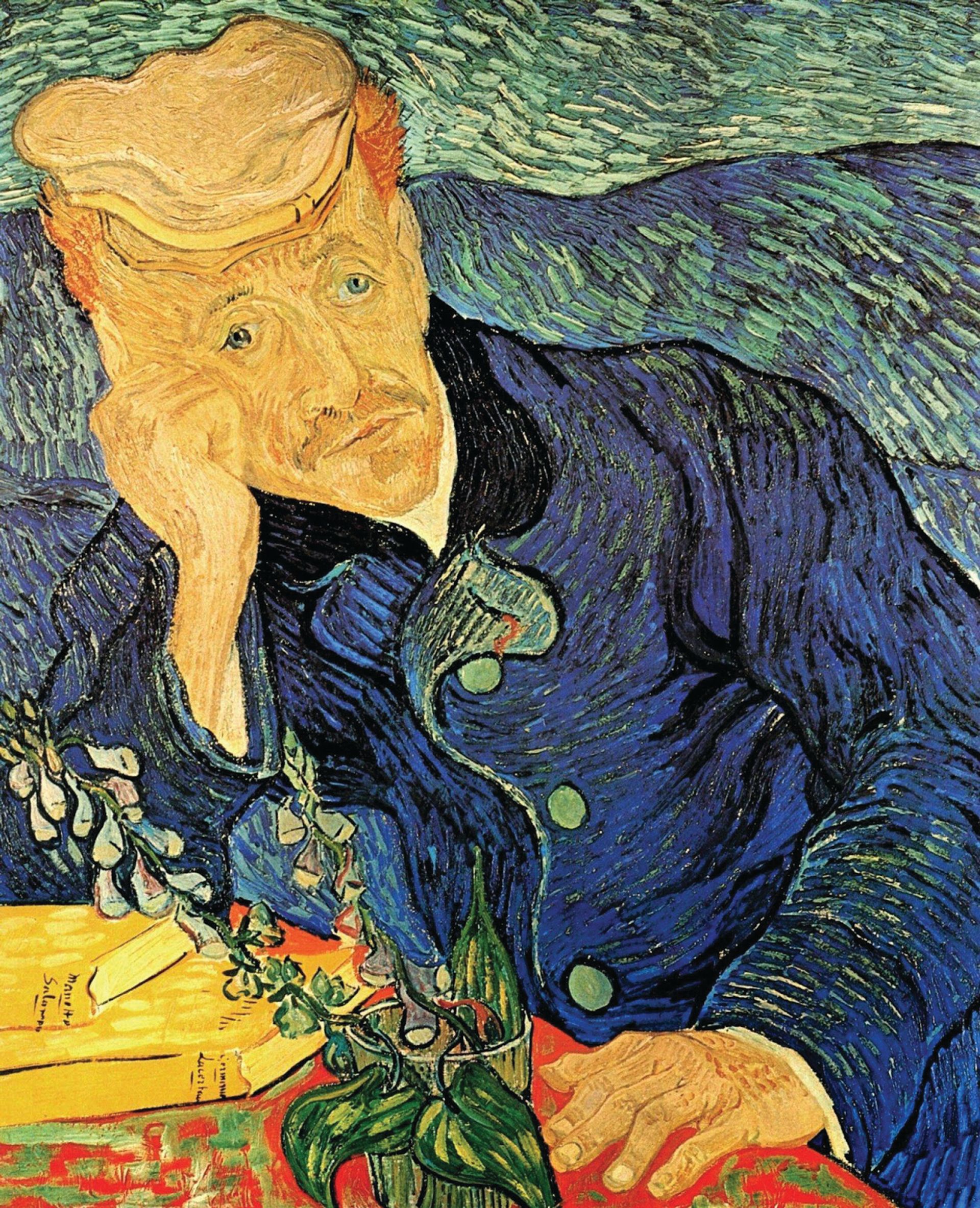

On 15 May 1990, Japanese businessman, Ryoei Saito, bought van Gogh’s Portrait of Dr Gachet (1890) for $82.5m at Christie's, New York, then the highest ever total paid for a work of art at auction and equivalent to around $154.5m today. Saito later announced that he wished to have the Van Gogh painting cremated with him when he died. Colleagues tried to explain that this was just a figure of speech, expressing the owner’s passion for the work, but the art world was concerned that one of the artist’s masterpieces would be lost. Saito later stated that he would consider giving it to a museum in his will, but the painting has not been seen since.

Saito died in 1996.

Not seen by the public since 1990: Vincent Van Gogh's Portrait of Dr Gachet (1890)

Reports surfaced in 2007 that the Japanese businessman had sold the painting to an Austrian collector, Wolfgang Flöttl, who later also sold it on, but its whereabouts remain unknown. A second version of the portrait, which Van Gogh was thought to have painted as a gift for Dr Gachet, is displayed at the Musée d’Orsay, though the authenticity of this version has been questioned: an examination showed that it contains underdrawings, contrary to van Gogh’s normal process of applying paint directly to a blank canvas.

Two days after the Saito bought the Van Gogh, he bought the smaller of two Renoir paintings entitled Bal du Moulin de la Galette for $78.1m (the larger canvas hangs in the Musée d’Orsay in Paris). That painting was used as collateral for loans to Saito’s businesses, and was sold by the banks involved when his companies experienced financial difficulties. It is now believed to be in a private Swiss collection, but has not been seen since 1990.

Should there be some legislation against the risk that a buyer will effectively or literally destroy a work of art? Particularly one which could be designated a “world treasure”, on a list of the sort that Unesco releases on protected monuments? One that would oblige private owners to make the works accessible within reasonable terms and require them to maintain the work, which could be considered a matter of international interest?

The art law specialist, Dr Edgar Tijhuis, points out that there has been a law in France since the 1890s giving the artist the right to protest against the mutilation or distortion of his work. In Holland, he notes, “the idea of a right to destroy gave way to the idea that you cannot do this, and nowadays there is a ‘duty of care’ for owners of art works.” In 1990, the US implemented the Visual Arts Rights Act, under which “a painter may insist on proper attribution of his painting and in some instances may sue the owner of the physical painting for destroying the painting, even if the owner lawfully owns it,” Tijhuis says. But, such laws exist country-by-country and are rarely enforced.

The process gets more complicated as the way that art is bought evolves. Consider the newly-founded Maecenas, based out of Singapore and run by Marcelo Garcia Casil. Their platform transforms art investment into a mutual fund. Maecenas works with specialists to target high-value works (worth in the low millions), and then allows vetted high-net-worth individuals to buy into the ownership of the object by paying in cryptocurrency. Maecenas then purchases the art with funds drawn from a number of investors, each putting in a smaller amount—normally in the hundreds of thousands, but potentially as low as $5,000—towards part-ownership of a high-end work of art.

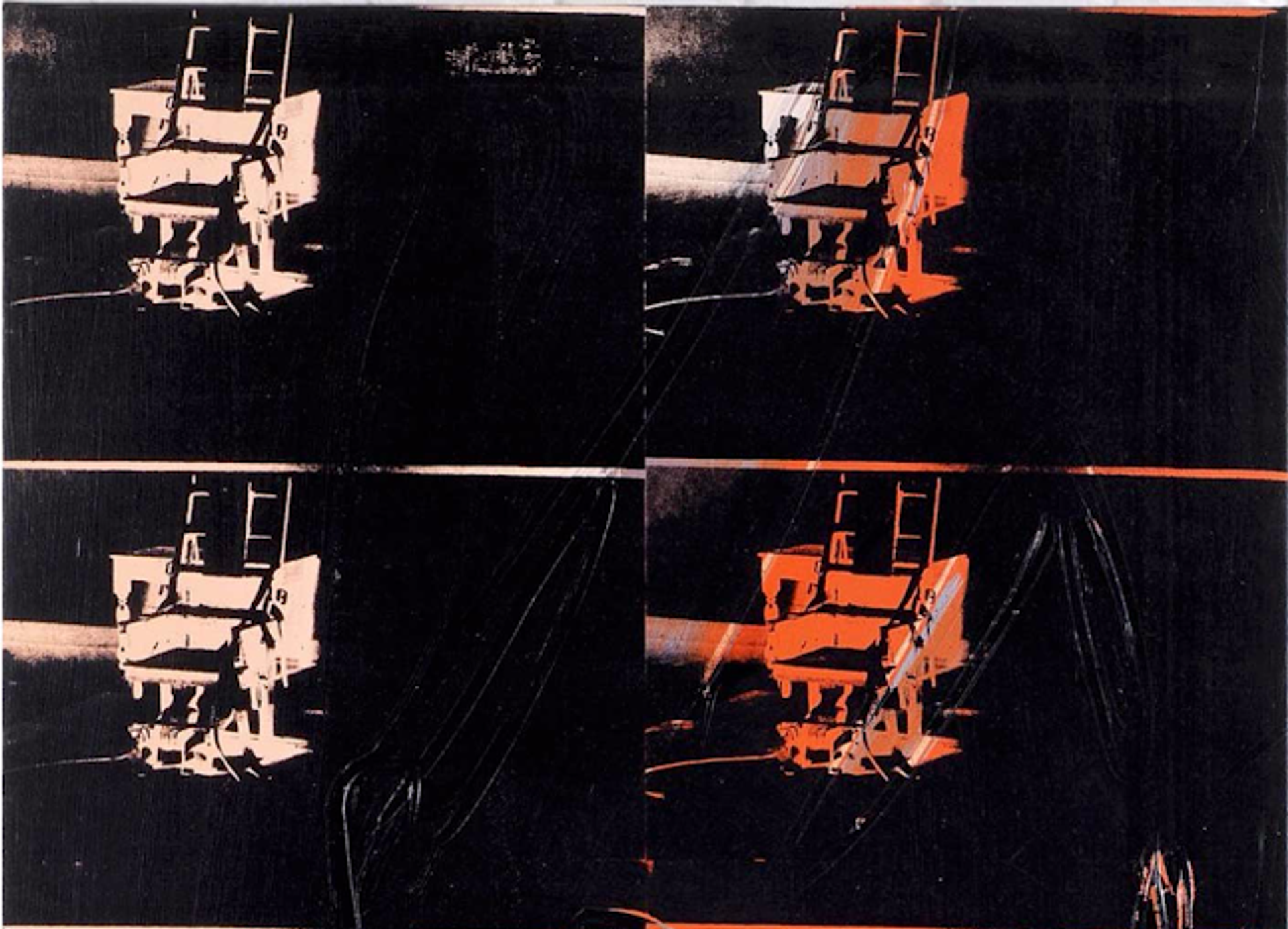

Bought by investors using blockchain, but still kept in a freeport: Andy Warhol's 14 Small Electric Chairs (1980, detail) Courtesy of Maecenas

As Garcia Casil explained to me, future selling-on fees are redistributed to the investors, as are any fees related to exhibition and image rights, and the entire process is made permanently transparent and tamper-proof through blockchain technology. He hopes that this will eliminate confusion over ownership and set provenance in virtual stone, so anyone can examine the object’s ownership and exhibition history.

The objects purchased, like Andy Warhol’s Fourteen Electric Chairs (1980), which Maecenas acquired for its investors this summer, remain in a secure freeport. This all sounds good, as does the idea that these work can be available for viewing under reasonable circumstances. But it does seem a shame for a beautiful object to sit in a vault, largely unseen.

• Noah Charney is an author and art history professor at the ARCA Postgraduate Program in Art Crime and Cultural Heritage Protection. His book Museum of Lost Art, is published by Phaidon