Chicago has a bold reputation for selling off its municipal assets. The city was the first to privatise an existing toll road; it sold its 911 emergency call operation to Sumitomo Mitsui Banking; and Chicago is still subject to ceaseless public ridicule for desperately leasing its parking meter system in 2008, a 75-year deal brokered for a lump sum of $1.2bn. In Chicago, as well as in other American Cities, the privatisation of city assets is a familiar scheme of sale-and-leaseback, offering tax shelters for buyers and a momentary revenue windfall for inadequate government coffers.

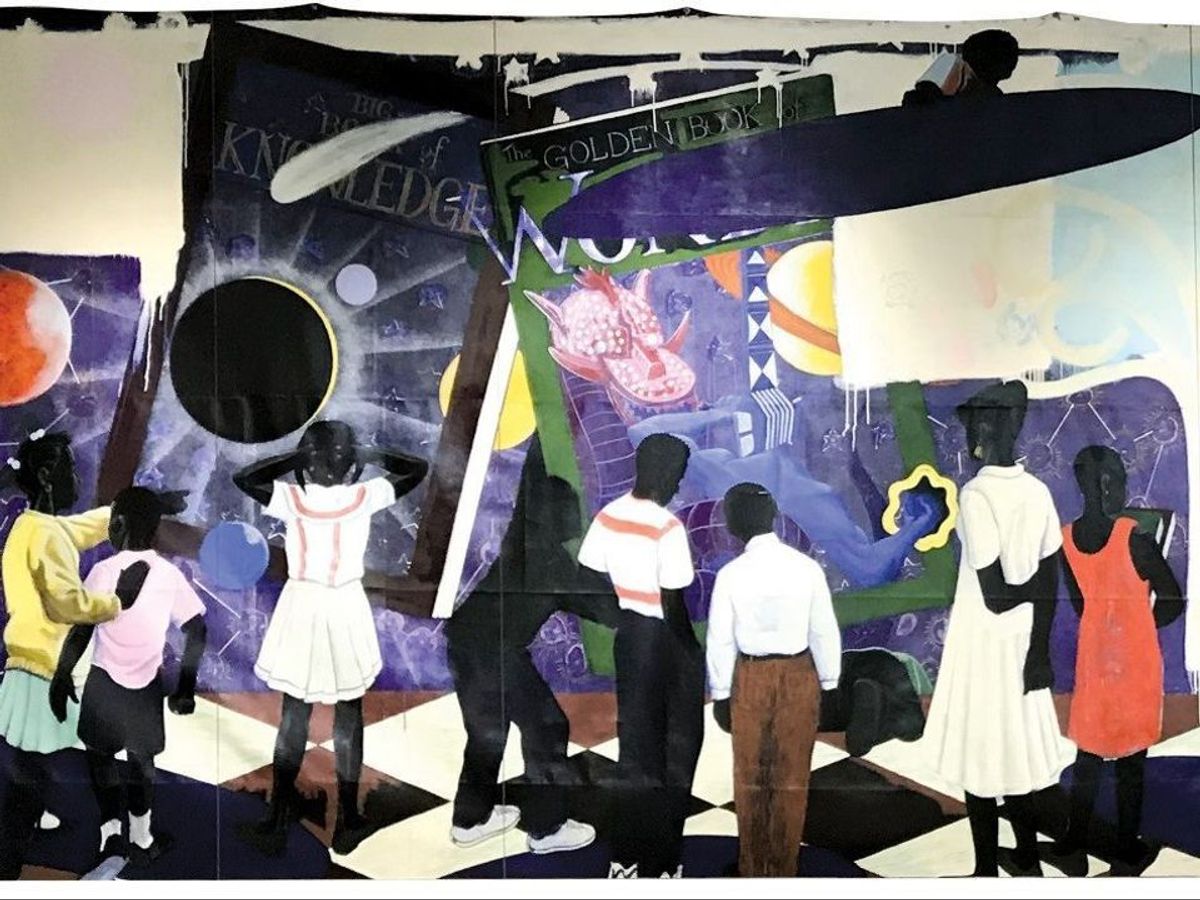

Chicago is also a black metropolis and home to an extraordinary number of black artists, many of whom are commanding attention in cultural discourses and global art markets. So, it is not surprising that the city recently identified another valuable asset in its holdings: Kerry James Marshall’s 1995 painting Knowledge and Wonder. Commissioned for the Legler Library Branch, it has been on public display in Chicago’s Garfield Park neighbourhood for nearly 25 years. Given the sale of Marshall’s 1997 painting Past Time by Chicago’s Metropolitan Pier and Exposition Authority earlier this year for a record breaking $21m, Knowledge and Wonder was tempting fruit.

Although Marshall’s site-specific painting was pulled from auction after public outcry, this change-of-heart does not amend the prevailing, uninspired, transactional value system that dominates all levels of our civic and cultural landscape. I am not just speaking of the city of Chicago now. I am speaking to the transactional comportment that contours everything from artist fees to granting organisations, from public deaccessions to public commissions.

Artists, curators, and arts administrators are all implicated in this shift. The days when value was mutable, indeterminate and experimental; when ideas around cultural worth could be deployed by artists with reflexive criticality has given way to hourly rates and standard fees. I am not saying that artists should not be compensated, but that compensation, when negotiated through a fixed transactional lens is no longer a fluid site of criticality.

Insidiously, we have come to confuse transformation with transaction. Transactional standards prioritise short term goals and demand predictable and fixed outcomes, seeking measurable results. Transformational work on the other hand is messy and drawn-out, but has the potential to challenge conventional standards of evaluation. Our transactional culture has impaired the artist-directed imagination and thwarted the virtue of evolving new artistic forms for the ease of guaranteed short-term results.

Chicago’s unabashed attempt to bring Marshall’s public mural to auction, and then to walk it back, clarified just how much power, freedom and education artists have lost in our transactional culture. It is not surprising that Marshall decided he would never create another public work after this experience. We may know the exact conditions of our work and exactly how much we will be compensated for it, but the price of this exchange comes at an immeasurable cost to the cultural imagination.

• Michelle Grabner is an artist and Painting and Drawing Chair at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago