The recent announcement by Chicago’s mayor Rahm Emanuel that the city plans to sell a monumental Kerry James Marshall painting installed in a historic library, is making public art advocates—and the artist himself—unhappy. "Considering that only last year Mayor Emanuel and [cultural affairs commissioner Mark} Kelly dedicated another mural I designed downtown for which I was asked to accept one dollar," Marshall said at the opening of his show at David Zwirner's London gallery, Wednesday night, "you could say the City of Big Shoulders has wrung every bit of value they could from the fruits of my labour."

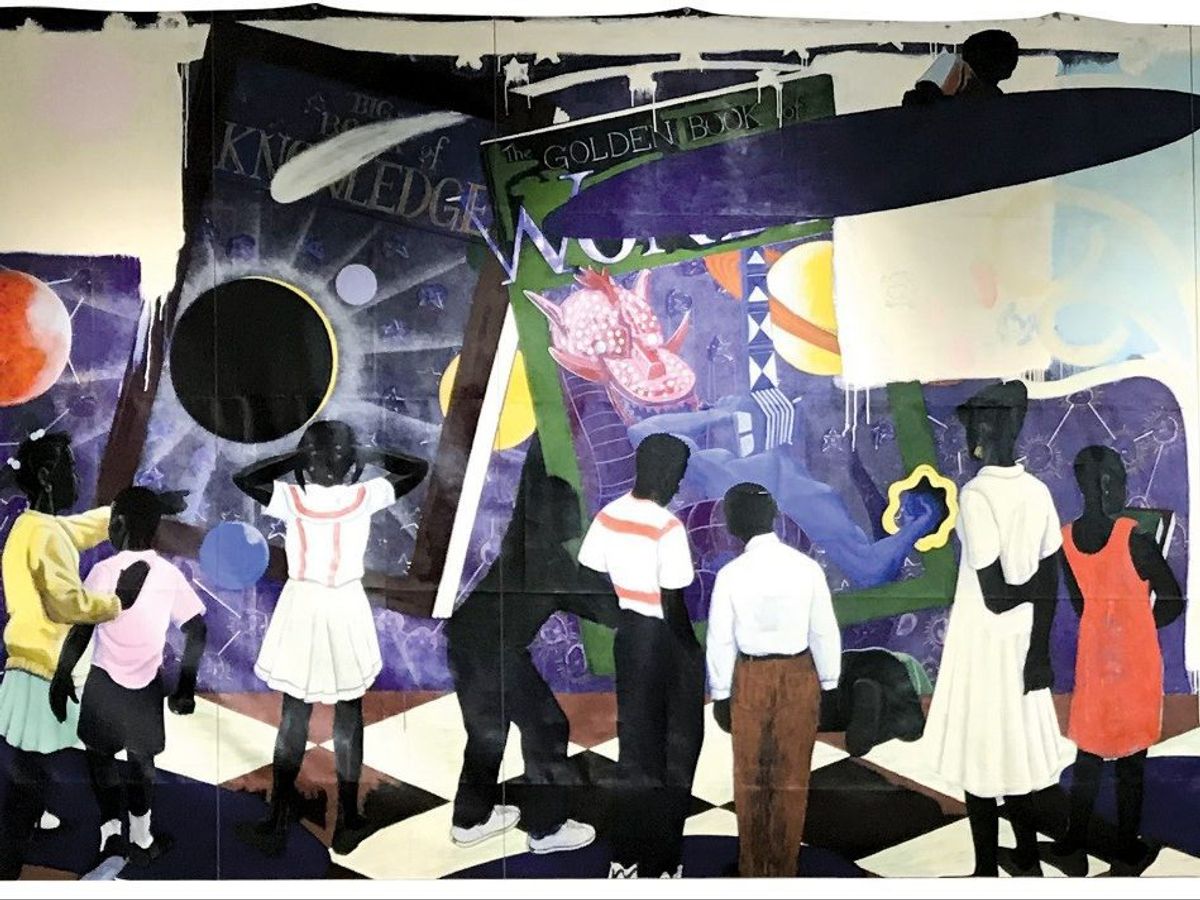

Created in 1995 for the Legler Branch Library near Garfield Park, Knowledge and Wonder is a panorama of black children gazing at giant cosmic picture books, which Marshall received a $10,000 commission fee for at the time. It is due to be auctioned at Christie’s, New York this November for an estimated $10m to $15m, with the city using the proceeds to benefit the city’s public art fund and library operations.

Earlier this year, the state-owned agency that operates the McCormick Place convention center removed another large painting by Marshall, Past Times (1997), and put it up for auction at Sotheby’s, New York this May. That work, which was included in the artist’s critically lauded travelling retrospective Kerry James Marshall: Mastry, sold for a record-setting $21m to the musician Sean Combs.

While it is common for cities and institutions to deaccession work, the impending sale of this site-specific work has generated an unusually loud emotional response. The photographer Dawoud Bey posted on Facebook: “Seems another Kerry James Marshall painting once displayed in a public space in Chicago is being removed and made ready for auction.” Lisa Yun Lee, a professor of art history at the University of Illinois and the director of the National Public Building Museum in Chicago, said: “This is not right. Someone should buy it and give it back to Legler on a long term loan and then work with AAM to stop public art theft through these acts of deaccessioning.” In an email, Lee said she is putting together questions for Museum Hue, a platform for creatives of colour, to explore “why certain communities have their cultural assets sold and taken from them in order to fund critical resources like libraries, and others get to preserve their cultural assets”.

The artist and non-profit arts administrator Barbara Koenen, who worked in Chicago’s cultural affairs department for more than 20 years with the maquette of Knowledge and Wonder hanging over her desk, decried the lack of public input and considers it wrong for the city to lose two works by this important Chicago artist. “I’m not a purist, I understand the need for the city to make money, but I would choose a different piece,” she said. She suggested the sculptor Richard Serra’s Reading Cones currently in Grant Park. “He has no connection to Chicago and the city has never known where to put it,” said Koenen. “It would be happy somewhere else.”

The art dealer Rhona Hoffman, who is a long-time friend of Marshall, is not pleased with the decision to remove the painting from the community. “If Kerry gave them permission to sell it for the benefit of a public art fund and the library, then bless them; if he didn’t, then the public library should be ashamed of themselves,” Hoffman said, adding: “I am very sad to see it leave the city.”

The news that Knowledge and Wonder would be sold did not surprise Dieter Roelstraete, who organised Mastry for the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago. After the Past Time, he said it was only a matter of time before Knowledge and Wonder, a hidden gem in a depressed neighbourhood on the west side of the city, would be seen as too valuable and unprotected. “It’s a loss for the city but it is not hard to understand why it would happen, the money can help keep the library going,” Roelstraete says. The curator said he did not attempt to borrow Knowledge & Wonder for the artist’s survey because it was logistically challenging “and it was the only thing the library had”.

Since the US does not have any federal resale rights laws for artists, Marshall will not directly benefit from the auction of Knowledge and Wonder, but his market has certainly improved. During the run of the Mastry exhibition, Roelstraete saw Marshall’s work skyrocket from the tens of thousands to the millions. “He is operating on a completely different level—conceptually and aesthetically he always was—and now finally the recognition is not only critical but has translated into the crude language of dollars,” Roelstraete says, “and that is fair and right.”