When is appropriation fair use and when is it foul? In a heated lawsuit, the Andy Warhol Foundation is asking a Manhattan federal court to “stay on the right side of history” and “reject” what it calls a photographer’s “effort to trample on the First Amendment and stifle artistic creativity”. For her part, Lynn Goldsmith, a celebrity and fine-art photographer, warns that a ruling in the Foundation’s favour “would give a free pass to appropriation artists” and destroy licensing markets for commercial photographers. Both combatants’ made their pleas in cross-motions for summary judgment filed Friday (12 October).

In 1984, Goldsmith granted Vanity Fair a one-time license to use her photograph of pop musician Prince as source material for an artist’s illustration. The artist was Warhol, who created not just the illustration for Vanity Fair but 15 other portraits of Prince. In 2016, the Foundation licensed one of those portraits to Condé Nast for $10,000 for the cover of a magazine devoted to Prince published shortly after the musician’s death. The portraits have been exhibited in museums, 12 were sold, and four are in the Andy Warhol Museum. Goldsmith says she learned of Warhol’s series from online images posted after Prince died.

The one licensed use she granted Vanity Fair “did not give Warhol free reign to then create 15 other versions” or the Foundation the right to license all 16, Goldsmith says. She contends the Foundation violated her exclusive rights under copyright law to reproduce, display, license and distribute works derived from her photograph.

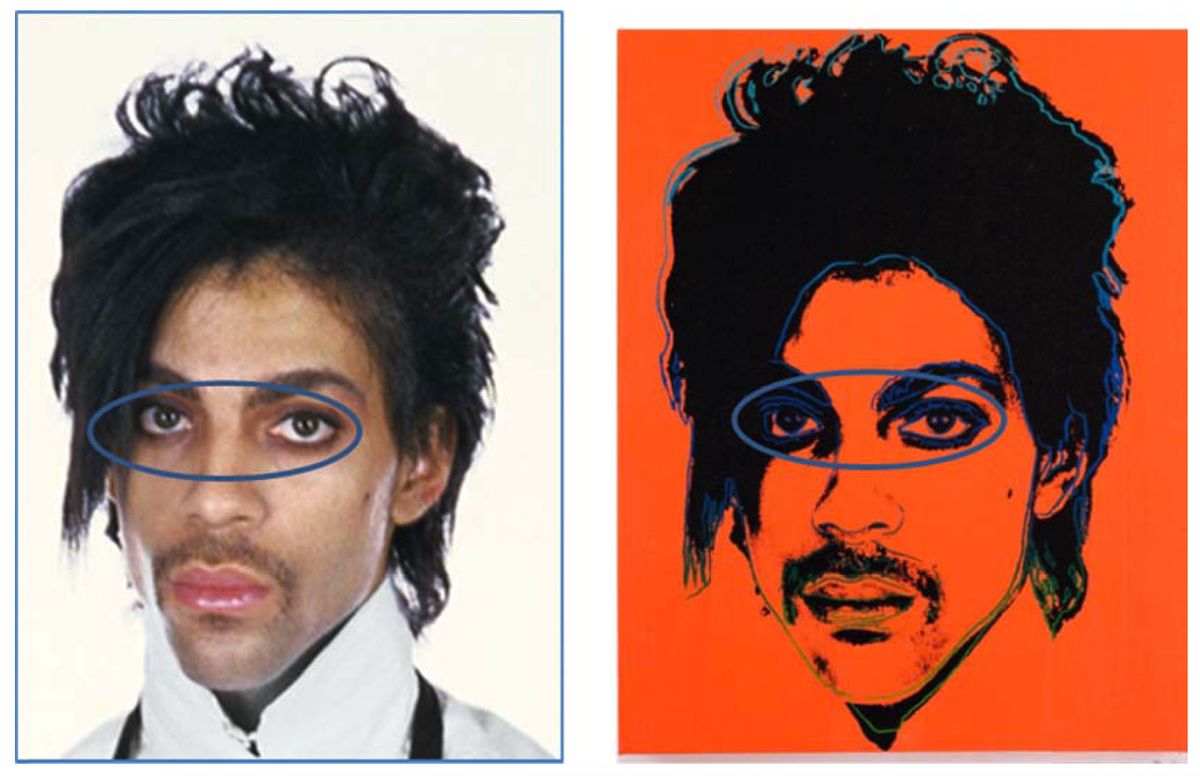

The Foundation first questions whether Warhol used Goldsmith’s image. “There is no evidence that he was given the photograph”, its papers say, but “somehow” he created the works. In any event, the Foundation continues, Warhol’s images fall under fair use in copyright law because they have a different aesthetic and meaning and do not usurp Goldsmith’s market. In cropping and flattening the image, he made it “disembodied and mask-like”. Whereas the photograph depicts Prince the person, Warhol’s Prince is an “icon or totem” commenting on celebrity and “defining the contemporary conditions of life”, the Foundation argues.

Warhol’s works do not compete with Goldsmith’s market, the Foundation contends: Warhols sell through high-end galleries and auction houses to wealthy buyers, Goldsmith through photography galleries targeting buyers interested in photographs of musicians.

According to Goldsmith, though, the aesthetic changes in Warhol’s images are “relatively minimal” and the series retains her photograph’s essence, composition, and such elements as Prince’s intense stare and the sheen from the lip gloss she applied. And, she argues, their licensing markets for commercial uses, including magazines, overlap. Her works are also in museums, and one wealthy collector owns one of her Prince photographs as well as Warhol’s works, she notes.

Goldsmith says the singular expression of Prince in her photograph “cannot be replicated by any other photo of Prince, but it can be substituted by the Warhol images that reflect the essence of that photo”. But to the Foundation, the lawsuit is really about “Andy Warhol’s legacy and protecting his transformative and innovative artistic works”.