For lawyers and legal scholars, just as for critics and historians, appropriation art raises a wide set of questions. The most important among them—what are the limits of fair use?—is at the centre of two high-stakes lawsuits now unfolding in Manhattan federal court. How the cases develop could offer some clarity to both photographers and to those who appropriate their work.

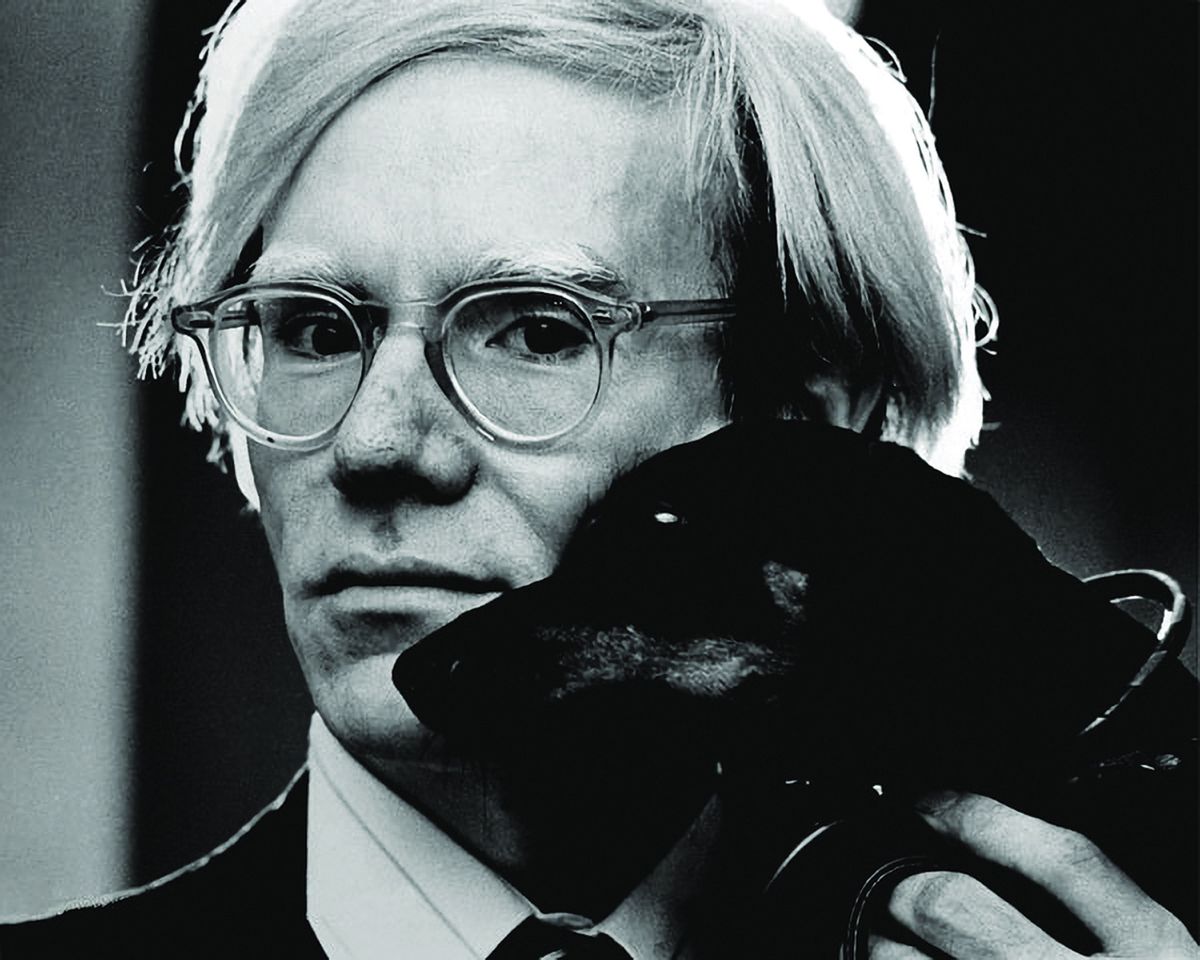

At issue are whether two art superstars—Andy Warhol, who arguably jump-started appropriation art, and Richard Prince, today’s high-profile practitioner—infringed photographers’ copyrights. “We will make new law,” says Luke Nikas, the Andy Warhol Foundation’s attorney.

US copyright law gives creators the right to control who uses their work. But an important exception is fair use, which The Copyright Act of 1976 illustrates (copyrighted material can be used for teaching and criticism, for example) but does not define. So the difficulty remains: how is fair use decided?

The new lawsuits highlight the difficulty of the question. In April, the Warhol Foundation, in a pre-emptive action, sued the photographer Lynn Goldsmith and her corporation, alleging that Goldsmith was trying to “extort a settlement”. The dispute revolves around a 1981 photograph she took of the singer Prince, which Warhol later used for a series of silkscreens. The foundation is asking the court to rule that Warhol did not infringe her copyright. In response, Goldsmith posted a video online describing how to make a “Warhol” in “four easy steps”. The parties even dispute which photograph Warhol used. Whatever the court rules, Nikas anticipates the decision will be appealed.

Nikas maintains that Warhol’s art is broadly understood as a quintessential example of fair use. If the court rules that Prince (1984), the Warhol example on hand, infringes Goldsmith’s copyright, “it would upset fair use law in a significant way”, he says.

To decide fair use, the court hearing the suit will consider several factors. Most important is how the original work is used. Does the new work parody the original? Parody is close to criticism and is generally fair use. Critical to analysing how Warhol used the photograph is whether his work is “transformative.” If he has altered the photograph with new meaning or expression, that favours fair use. Then there is the question of how much of the image Warhol took; the more that has been taken, the more it leans towards infringement. Another crucial problem is whether the new work negatively affects the market for the original. If it is deemed to usurp that market, that, too, leans towards infringement.

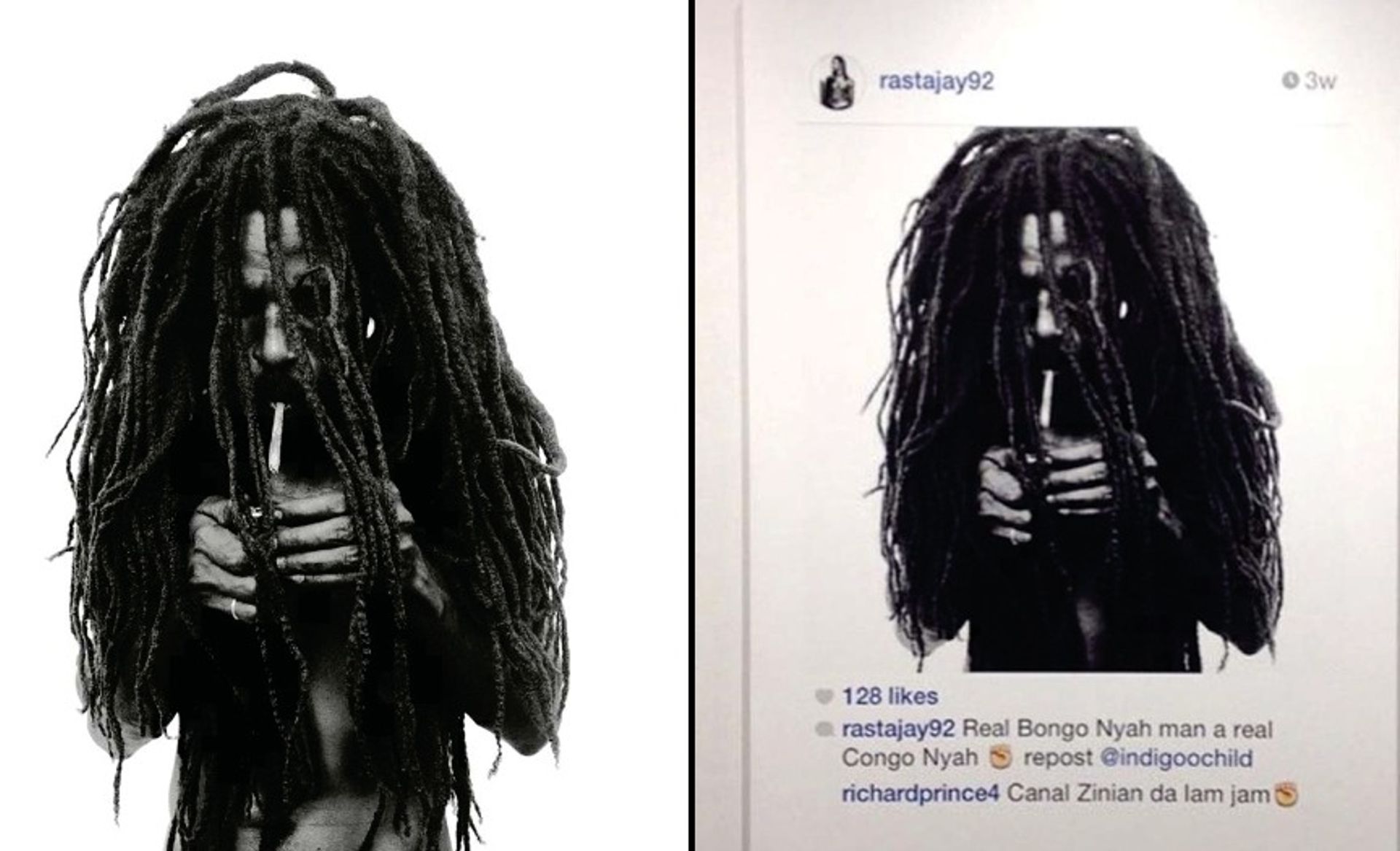

Donald Graham's photography, left, and Richard Prince's Instagram print, right

Expansion of fair use

The Warhol lawsuit is proceeding in the charged atmosphere created by a controversial 2013 court decision. Then, the Second Circuit considered whether 30 works by Richard Prince infringed Patrick Cariou’s photographs. In what is widely seen as an expansion of fair use, the court said that the most important factor in determining fair use is whether the “reasonable observer”—the judge or jury—sees the allegedly infringing work as “transformative”. Comparing Prince’s “jarring” works side-by-side with Cariou’s “serene” photographs, the appellate court found that 25 were fair use because they had a “new expression” and a “different aesthetic”. It sent five, less altered works, to the lower court to rule on, but the parties since settled those claims.

The decision “is so controversial that even other circuits have raised questions about whether the transformative test is too broad”, says Dale Cendali, a partner at Kirkland and Ellis law firm who wrote an amicus brief supporting Cariou’s position. For photographers, the decision created “more of a hostile environment”, says David Leichtman of Leichtman Law, who wrote a similar brief. And for artists who copy, the decision’s reliance on aesthetics creates “significant uncertainty about limits”, especially for conceptual art where meaning doesn’t always depend on the work’s appearance, says the New York University law professor Amy Adler, who consulted for Prince’s lawyers in the case.

Now Richard Prince is at the centre of another case that some consider a test of appropriation’s legal limits because the only formal change made to the appropriated photograph is some minimal cropping of the image.

In 2014, the artist took a screenshot of an Instagram picture taken by a user named “rastajay92” that included a photograph by Donald Graham. Without asking Graham’s permission, Prince blew up his screenshot, which included a cryptic comment made by Prince’s own Instagram account, and presented it in an exhibition at Gagosian gallery. In April 2016, he requested a ruling that his work was fair use before any evidence was even developed. “Richard’s goal is upholding the principle of fair use, which he thinks of as first amendment free speech values”, says Prince’s lawyer, Josh Schiller.

After considering the questions that are typically asked when determining fair use, the judge, Sidney Stein, denied his motion in July 2017. “Given Prince’s use of essentially the entirety of Graham’s photograph”, Stein said, it would not be possible to establish the new work as transformative “without substantial evidentiary support”.

What evidence will the “reasonable observer” be allowed to consider? “Contemporary art may not get its meaning purely from the visual,” Adler says. She cites Sherrie Levine’s photographs of Walker Evans’s photographs. They are visually identical but have different meanings; scholars often interpret Levine’s as commenting on originality.

Schiller wants the judge to consider what critics wrote about the exhibition at Gagosian “to show people saw new meaning and that was transformative”. Similarly, Nikas argues that the judge should allow connoisseurs, scholars and other experts to testify that the Warhol works in question differ from the photograph, whatever the visual similarities. Whether they succeed may influence who wins. The Cariou-Prince case did not settle whether experts could testify.

“This case [the new Warhol suit] will do that,” Nikas says. Goldsmith’s lawyer, Barry Werbin, would not comment on the suit, but says flatly that “no expert testimony is needed” to determine whether a work is transformative.

Andy Warhol

What would a “reasonable observer” conclude?

The Andy Warhol Foundation’s complaint against Lynn Goldsmith and her corporation argues that Warhol’s portrait of Prince “fundamentally transformed the visual aesthetic and meaning” of her photograph. Among other things, the foundation points to heavier makeup around the subject’s eyes, the unnatural colours of the work and the flattening of the image. Warhol’s portrait, the complaint says, “may reasonably be perceived as simultaneously honouring the celebrity of Prince while also conveying that Prince... is a manufactured star with a stage name, whom society has reduced to a commodity”.

In her counterclaim, Goldsmith contends that Warhol’s work retains “all the essential and distinctive elements” of her photograph, “from the detailed hair curls atop Prince’s head to the... composition and Prince’s head pose, the deep-set intensity of Prince’s eyes, his pursed lips, facial hair details, and his self-reflective stare into the eye of the camera as if pondering his newfound stardom”.

Richard Prince

Copyright and social media

In court, one of Donald Graham’s lawyers, David Marriott, said the addition of a comment by Richard Prince to Graham’s photograph was not transformative. If “it is enough to avoid a claim of copyright infringement to simply post an image and add whatever four words you want... there is effectively no [copyright] protection of works of this kind in the context of social media”.

Judge Sidney Stein, however, has suggested that “this is not a simple reposting. This is an enlarging, a putting on a canvas, and exhibiting in a public art forum”. (The work was shown at Gagosian gallery in New York in 2014 and the gallery and Larry Gagosian have been named as a co-defendants.)

Marriott responded that it is immaterial that Prince is an artist. “It doesn’t matter that it is Richard Prince... There isn’t a copyright and fair use doctrine that applies to famous, rich... artists and a different one that applies to the rest of us”. He added: “If what they did here is permissible fair use, then virtually anything can be posted with the slightest of commentary and it somehow is now transformed into a protectable piece of work”.