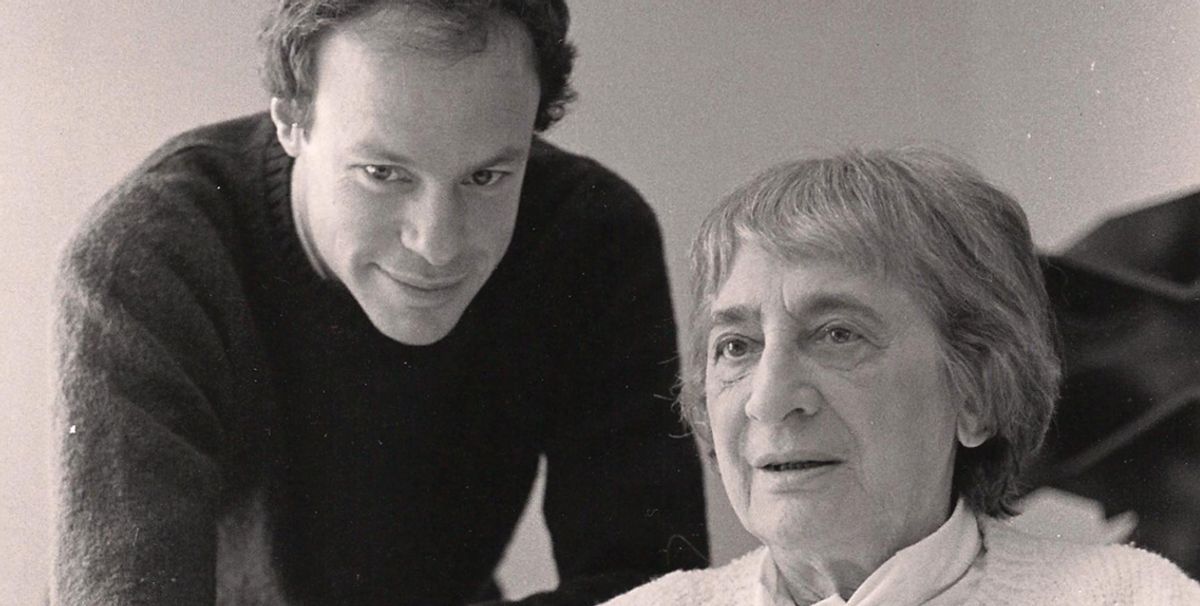

Paul Smith first became aware of Albers and the Bauhaus when in hospital as a young man; now he is collaborating with her foundation Luke MacGregor/Reuters

Growing up in Nottingham, England in the 1950s and 60s, the fashion designer Paul Smith was obsessed with bicycles and dreamed of becoming a professional cyclist. But a serious accident landed him in hospital for several weeks, putting paid to his fledgling sporting career. Although the experience was utterly depressing (he says 16 people died on his ward while he was there), it was while in hospital that he made friends with students from the local art college, who introduced him to the radical Bauhaus school and its teachings.

“It was then that I first became aware of the work of Josef and Anni Albers,” says Smith, who is collaborating for the first time with the artists’ foundation on a capsule collection, due to launch on 11 October, the same day that the first UK retrospective devoted to the work of Anni Albers opens at Tate Modern. “My career in fashion can be traced back to those early discussions with the art students about the Bauhaus, about the Alberses and so much more besides.”

Smith has already paid homage to the Alberses in his work. In 2015 he designed a catwalk collection featuring bold geometric check patterns and dusky colours that were directly influenced by Anni’s textiles and Josef’s paintings. He also designed an Albers-inspired collection of rugs, handwoven wall hangings and fabrics for the Rug Company last year.

Anni Albers’s Eclat pattern, first made in collaboration with Knoll in the 1970s, is still available today © The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation and Knoll Textiles/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/DACS, London, 2018

By contrast, the new knitwear collection is “a collaboration in the purest sense”, says Nicholas Fox Weber, since 1979 the executive director of the Josef and Anni Albers Foundation (the non-profit organisation was established in 1971, when both artists were still alive). Working with commerical brands was a crucial part of Anni Albers’s career: she worked with Florence Knoll on a series of designs over 30 years. They include her classic Eclat pattern from 1976, in which a series of paralellograms jostle in seemingly constant movement, yet with immaculate order. The design is still produced by Knoll today. Now, the Albers foundation has licensed one of Anni’s designs, Wallhanging (1925), which Smith has translated into a 180cm by 50cm pattern to create limited edition cashmere jumpers and wool accessories such as blankets and scarves, punctuated with pinstripes. The rich palette—with evocative names such as tobacco brown, air blue and cloud dust—is Smith’s own, but clearly references those that emerged from Anni Albers’s loom.

Besides a shared colour sensibility, Fox Weber detects several common threads between Albers and Smith, whom he first met three years ago at the Museo delle Culture di Milano, where Fox Weber had organised an exhibition focusing on the Latin American influence on the Alberses. Titled A Beautiful Confluence, it combined their work with pre-Columbian objects in the museum’s collection, as well as artefacts the couple amassed during their many trips to Mexico from 1935 onwards (they fled Nazi Germany for America in 1933).

As they walked through the show together, Fox Weber was struck by the absorption with which Smith viewed the works. “He would look at things and notice them with a detail and an intensity that are very rare,” he says. “I had that sensation once before, when I took Anni to the British Museum when she was 91 years old. I knew she had never seen the Elgin Marbles, but what most interested her were not the marbles but the Minoan and Mycenaean pieces there. The way she engaged with them, it was as if there was an electric current between those objects and her.”

Smith is also attuned to the element of surprise in Anni Albers’s work, something he likes to introduce to his own designs, Fox Weber observes. “Paul might create a very conservative pinstripe suit that you think is absolutely for a traditional banker in the City. And then the banker reaches for something inside his breast pocket and discovers that the lining is a bright crimson or lavender,” he says. “That’s the kind of surprise Paul likes.”

Paul Smith’s capsule collection includes a scarf, blankets and cashmere jumpers based on Albers’s design © Paul Smith

Such collaborations are just one of the myriad ways in which the legacy of Josef and Anni Albers has been, and continues to be, preserved. As well as working with with designers and choreographers, the foundation supports several philanthropic projects, including two in the west African country of Senegal: a cultural centre offering artist residencies in the remote village of Sinthian, and the planned expansion of the Tambacounda Hospital by the German architect Manuel Herz.

As with any foundation, a fundamental mission is to promote and protect the artists’ markets. David Zwirner gallery this year announced its commercial representation of the foundation, no doubt a welcome boost when the issue of fakes is to the fore. At the time of writing, Fox Weber was due to testify for the first time in his career in a case concerning an allegedly forged Josef Albers painting.

For all the right reasons, however, Anni is currently in the spotlight. The Tate Modern retrospective “will show Anni was a pure abstractionist, more so than Josef even”, Fox Weber says. He describes it as ironic that people are pricking up their ears because of the collaboration with Paul Smith, given that she has often been described as a female artist overshadowed by her husband. “It was a notion Anni pooh-poohed during her lifetime,” he says. “When people would ask her what it was like to be married to a world-famous artist, she would reply: ‘Well, I’m not buying his socks.’”

• Anni Albers, Tate Modern, 11 October-27 January 2019. The Paul Smith x Anni Albers collection is available for pre-order now at paulsmith.com