While Brexit continues to pose questions for the UK art trade, British-South African relations could be strengthened after Britain leaves the EU. During her trip to South Africa in August, the British prime minister Theresa May announced a $5bn investment in African economies and post-Brexit trade deals with six countries.

South Africa was among them, although, as Frank Kilbourn, the chairman of South Africa’s leading auction house Strauss & Co points out, the two countries have long enjoyed a “strong trade relationship”. Whether the art market will reap the benefits of May’s deal remains to be seen, he adds.

At Frieze London this year, it would seem South African galleries are ahead of the political curve, showing homegrown talent, many of whom engage with domestic and international politics. The Cape Town-born artist Haroon Gunn-Salie’s sculpture, Senzenina (2018), is on show as part of Frieze Sculpture Park (until 7 October). The work consists of 17 headless, kneeling bronze-cast figures and commemorates the Marikana massacre of 2012, in which 34 miners on strike were killed when police opened fire on them.

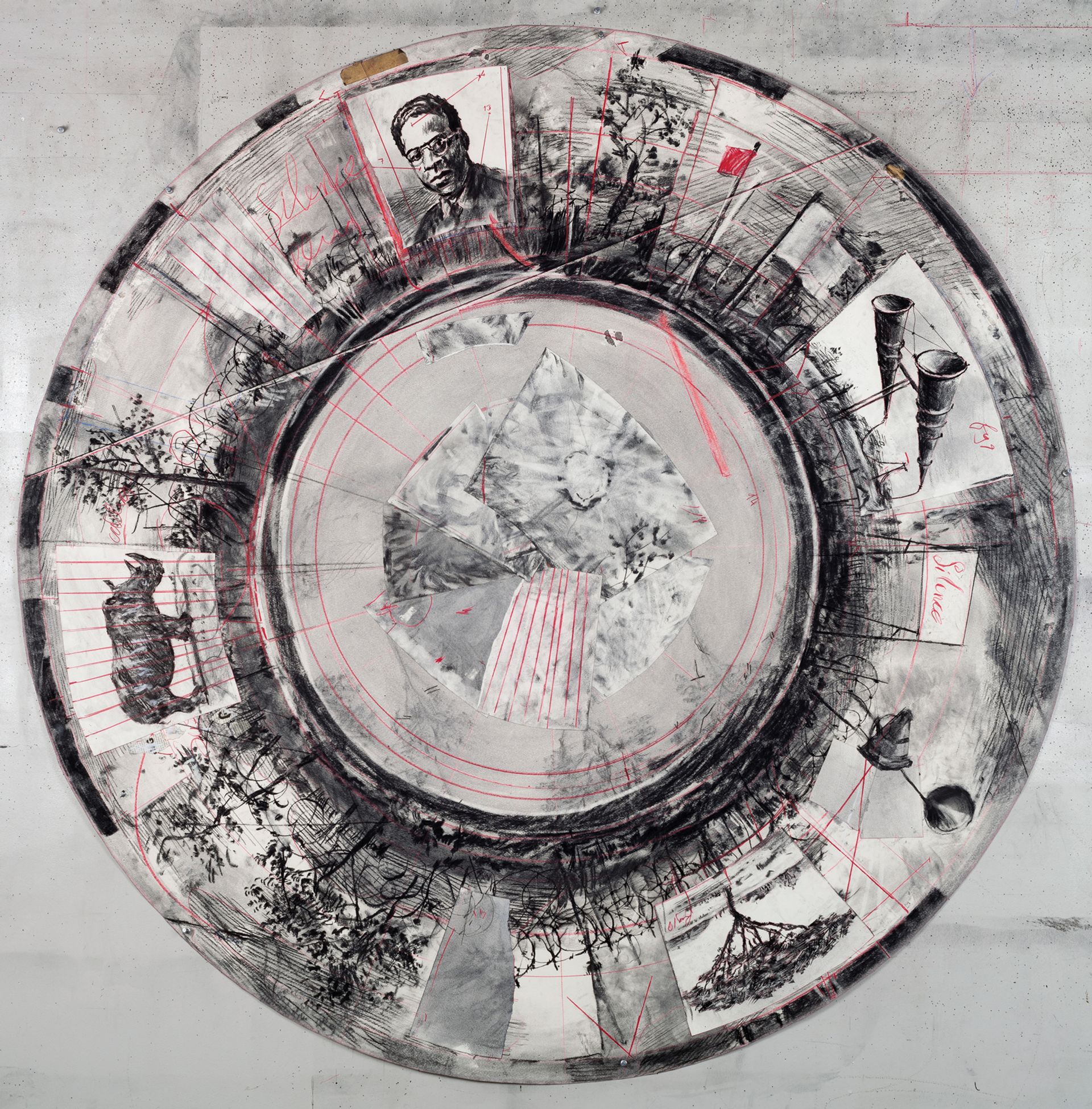

Gunn-Salie is represented by Goodman Gallery (Cape Town and Johannesburg), which is also bringing a new drawing by one of South Africa’s best-known exports William Kentridge made for his production, The Head & the Load, which premiered at Tate Modern in July. The performance tells the story of the millions of African porters and carriers who were involved in the First World War. Prices on the booth range from $10,000 to $1.2m.

Kentridge’s Untitled (Drawing for the Head & the Load, Tondo) (2018) Courtesy of Goodman Gallery and the artist

The Cape Town gallery Blank Projects is showing three South African artists: Cinga Samson, Donna Kukama and Bronwyn Katz. Meanwhile, Marian Goodman Gallery’s stand includes works by the rising star Kemang Wa Lehulere. His solo show, Not Even The Departed Stay Grounded, which addresses the enduring apartheid system even after democratic elections, is at the London gallery until 20 October.

Liza Essers, the director of Goodman Gallery, which was established in 1966 at the height of apartheid, says censorship is “not as big of an issue now as it was then”. She believes, however, that it is important to “facilitate the voices” of artists such as Gunn-Salie, “so that we can avoid the need to once again have to fight against censorship”.

Another issue affecting the South African market is the weak rand. However, Kilbourn says a devalued currency, on top of relatively cheap prices, make South African art an attractive prospect. Strauss & Co brought directors to London to meet clients in September, although there are “no immediate plans” to launch sales in London, Kilbourn says. He estimates that around 50% of works by contemporary South African artists are now sold to international buyers. The auction house is hoping to capitalise on the growing popularity of African art: “Over time, the nature of the works we sell will change to reflect that the primary and secondary markets for contemporary art are moving closer together.”

• Frieze London, Regent’s Park, London, 4-7 October