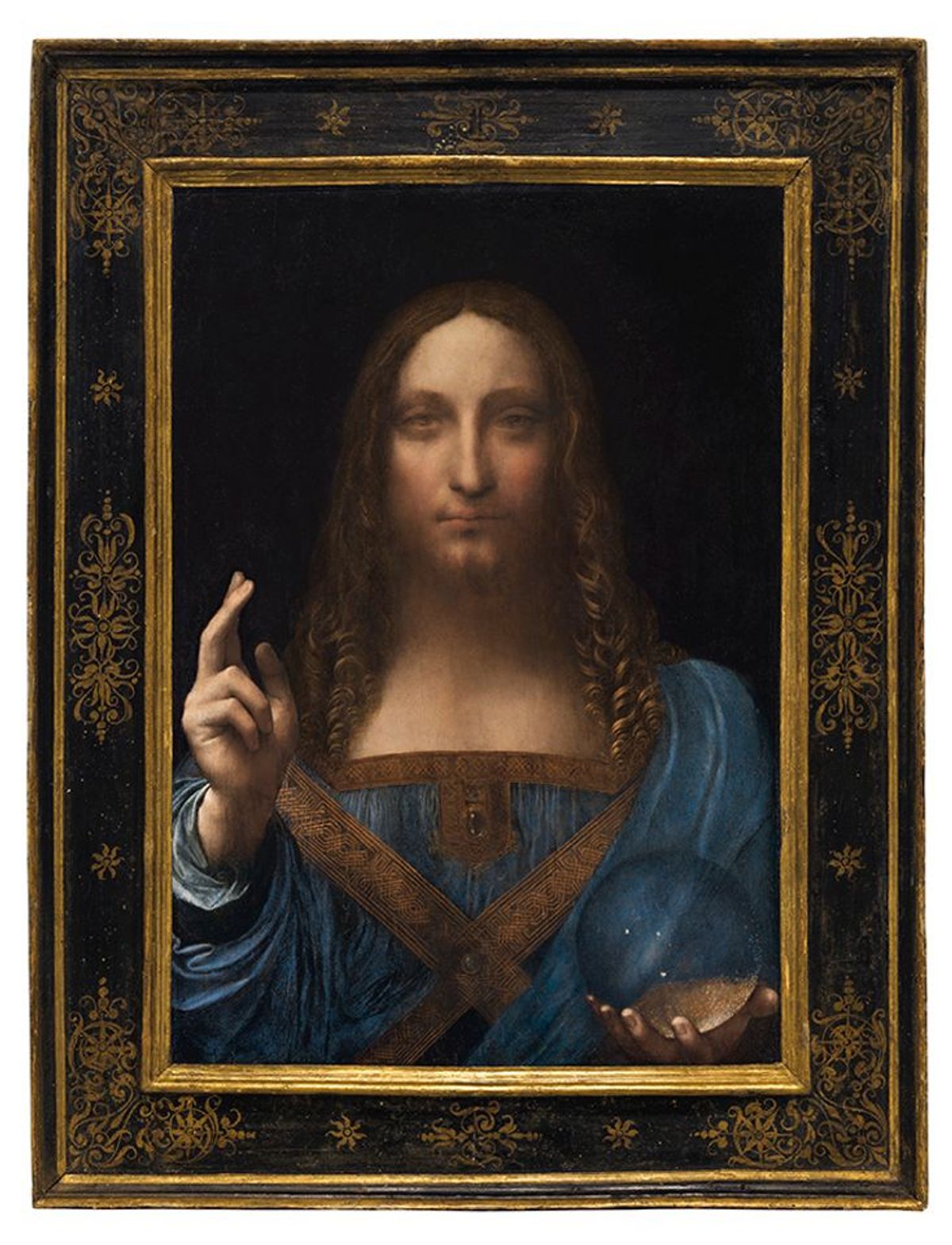

The contemporary saga of the 16th-century Salvator Mundi painting continues after news broke on Tuesday (18 September) that the work spent nearly 50 years in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. The Wall Street Journal reports that it was part of a family home collection there, the owners of which had no inkling that it was painted by Leonardo da Vinci.

Currently the most expensive work of art in the world having sold for $450m at Christie’s in New York last November, the long-lost Leonardo painting was in the possession of Basil Clovis Hendry Sr, who owned a Louisiana sheet-metal company, before Old Master dealers Robert Simon and Alexander Parrish bought it from the family's estate sale in New Orleans in 2005 for less than $10,000.

Hendry’s daughter, Susan Hendry Tureau, a 70-year-old retired library technician still living in Louisiana, learned just last week that the painting was reauthenticated as a Leonardo, according to the Wall Street Journal. She doubts whether her father ever considered the work to be such rarity, which is unsurprising given the extensive and heavy-handed restorations it had undergone over the centuries. The work had been handed down to Hendry after the 1987 death of his aunt, Minnie Stanfill Kuntz, who “often travelled to Europe”, where she and her husband frequently purchased art and antiques.

By cross-referencing photographs, auction catalogues, obituaries and travel documents, the Wall Street Journal uncovered that the Kuntzes returned from a trip to England in the summer of 1958, around the same time a portrait of Christ attributed to “the school of da Vinci” was sold at Sotheby’s in London for £45 (about $120) on 25 June 1958, recorded as Kuntz Private Collection USA in the auction house’s official provenance records. That work has been established as a previous misidentification of Salvator Mundi, although the identity of the Kuntz buyer had remained a mystery until now.

The long-lost Leonardo painting has a patchwork provenance that places it in the hands of English kings, Russian oligarchs and, most recently, Saudi Arabia’s Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman. Yet gaps and overlaps in its ownership history have been the subject of scrutiny among scholars and connoisseurs, as reported on the front page of The Art Newspaper’s September issue. Rumours never cease to swirl around the work, especially after its display at the Louvre Abu Dhabi, scheduled for 18 September, was inexplicably delayed.

Dealer Robert Simon, who was instrumental in reattributing Salvator Mundi to Leonardo, says of the recent news: “Of course we knew where we had purchased the painting so that was hardly news for us.” While he also knew the identity of the estate that had consigned it to auction, he had been restricted from divulging the information due to a non-disclosure agreement—the only one he’s ever had to sign in his entire art dealing career. Simon says it is “a relief” to release more details surrounding the work’s history.

“When you consider the amount of literature that’s been written about every other Leonardo out there—most of which have been known for centuries—it’s inevitable that more and more will come to light on this work, which has only been known to the public for a few years,” he says. The Salvator Mundi may hold many more mysteries. But Simon says the Wall Street Journal’s research, if accurate, solves at least one, “how it made its way to from London to Louisiana.”