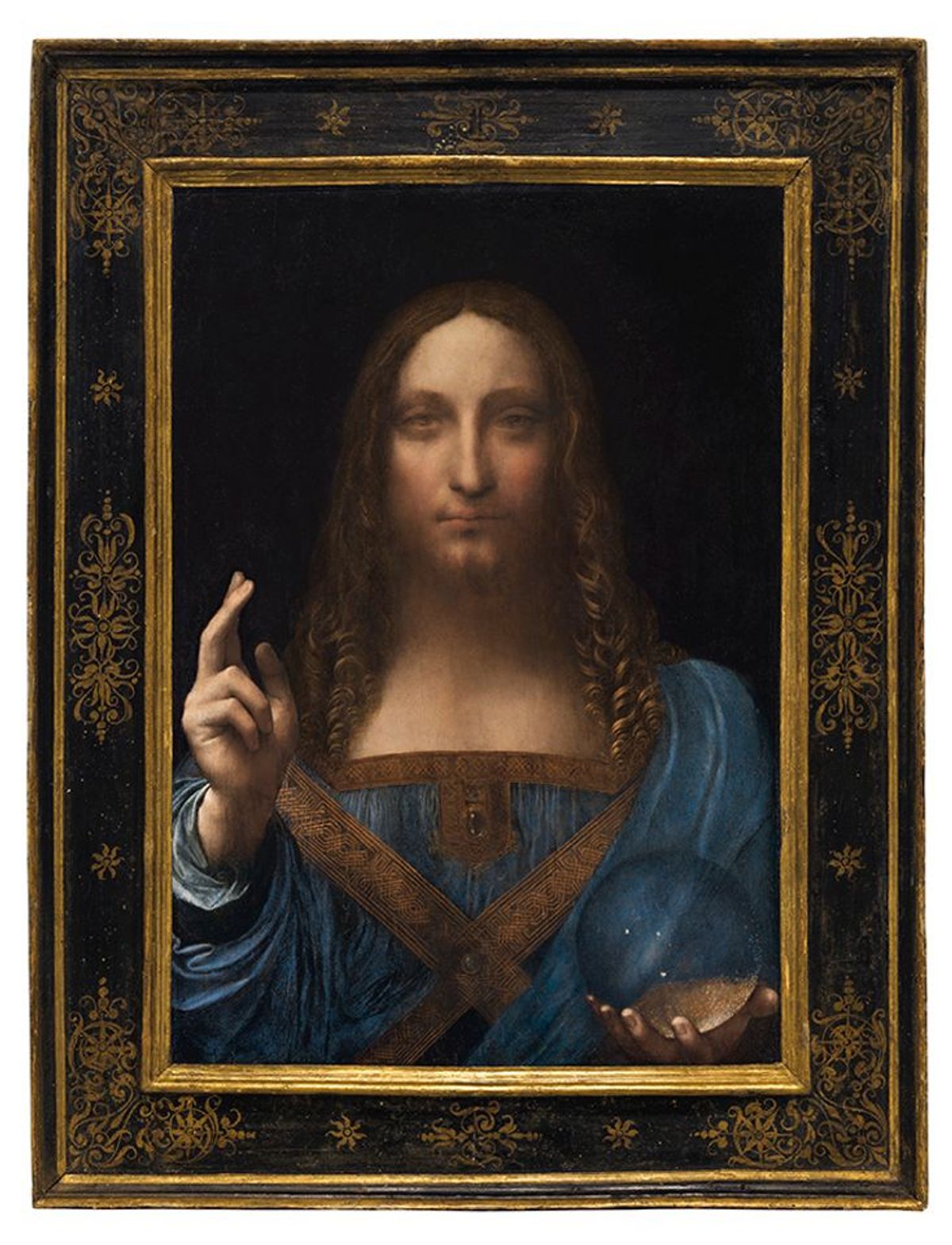

As Louvre Abu Dhabi unveils Leonardo’s painting of the Salvator Mundi this month, fresh evidence has emerged that throws into question the early whereabouts of the painting and its royal pedigree.

Until now, it was thought that the painting was “possibly” made for Leonardo’s patron King Louis XII of France and his consort Anne of Brittany, who “most likely” commissioned it from the artist soon after the French conquest of Milan, around 1500 (according to the sale catalogue published by Christie’s in November 2017). The Leonardo Salvator Mundi next emerges in 17th-century England, as the property of Charles I, at the height of the Civil War. It is a richly suggestive narrative: made for a king and fit for a king.

Scholars propose that when the French princess Henrietta Maria married King Charles I in 1625, she may have brought the picture with her, and that it remained in her Greenwich apartments—as royal property—until the king’s execution in 1649. It has been identified with “A peece of Christ done by Leonardo” (recorded in the Commonwealth Sale of 1651).

But now, new research by the 17th-century specialist Jeremy Wood situates a Salvator Mundi by Leonardo in the Chelsea home of James, 3rd Marquis, later 1st Duke of Hamilton, between 1638 and 1641, rather than in Queen Henrietta’s chambers. This raises the question of how the picture could be in two places at once: Hamilton’s Chelsea house and Henrietta’s Greenwich closets.

James Hamilton (painted by Van Dyck in 1640) owned a work similar in description to Leonardo’s Salvator Mundi The artist; Liechtenstein; Princely Collections

Margaret Dalivalle, whose expertise on the Salvator Mundi’s provenance is one of the pillars of connoisseurship that underline the attribution to Leonardo, spotted the importance of Wood’s “exciting discovery” in his essay (Buying and Selling Art in Venice, London and Antwerp… c.1637-52, recently published by the Walpole Society), which presents an inventory of the paintings in Hamilton’s home from around 1638 to 1641.

Dalivalle says: “I immediately recognised the significance of one item hanging in the Lower Gallery: ‘Christ: with a globe in his hande done by Leonardus Vinsett’”—the artist now known uniformly as Leonardo da Vinci.

“The precision of the description in the Hamilton inventory is itself vanishingly rare in a 17th-century English document, as is a painting attributed to Leonardo,” Dalivalle says. “[The inventory entry] sounds feasible to me… given the company it kept; it was placed among paintings of prestigious Della Nave and Priuli [both notable Venetian collections] provenance.”

There are 20 painted variants of the Salvator Mundi by an assortment of Leonardo’s pupils and followers. If the pictures can both be identified as the Salvator Mundi in Abu Dhabi, Dalivalle has a plausible scenario as to how the painting found its way from Hamilton’s collection into the ownership of Charles I. “The painting was in a collection closely, almost incestuously, related to the Royal Collection; the king, according to a document of 18 October 1638, expressly wished to have the pick of paintings bought by Hamilton in Venice, threatening the imposition of customs duty, and the king and queen’s predilection for Leonardo is documented,” Dalivalle says. “Therefore, I consider there is a strong possibility that this painting was seen at Chelsea House and chosen by the king at some point between 1638 and 1641, finding its way to the queen’s apartments at Greenwich.”

She adds: “I have found no evidence that the Salvator Mundi was brought by Henrietta Maria from France; it belonged to her by dint of the fact that it was recorded in a property of her jointure in 1649.”

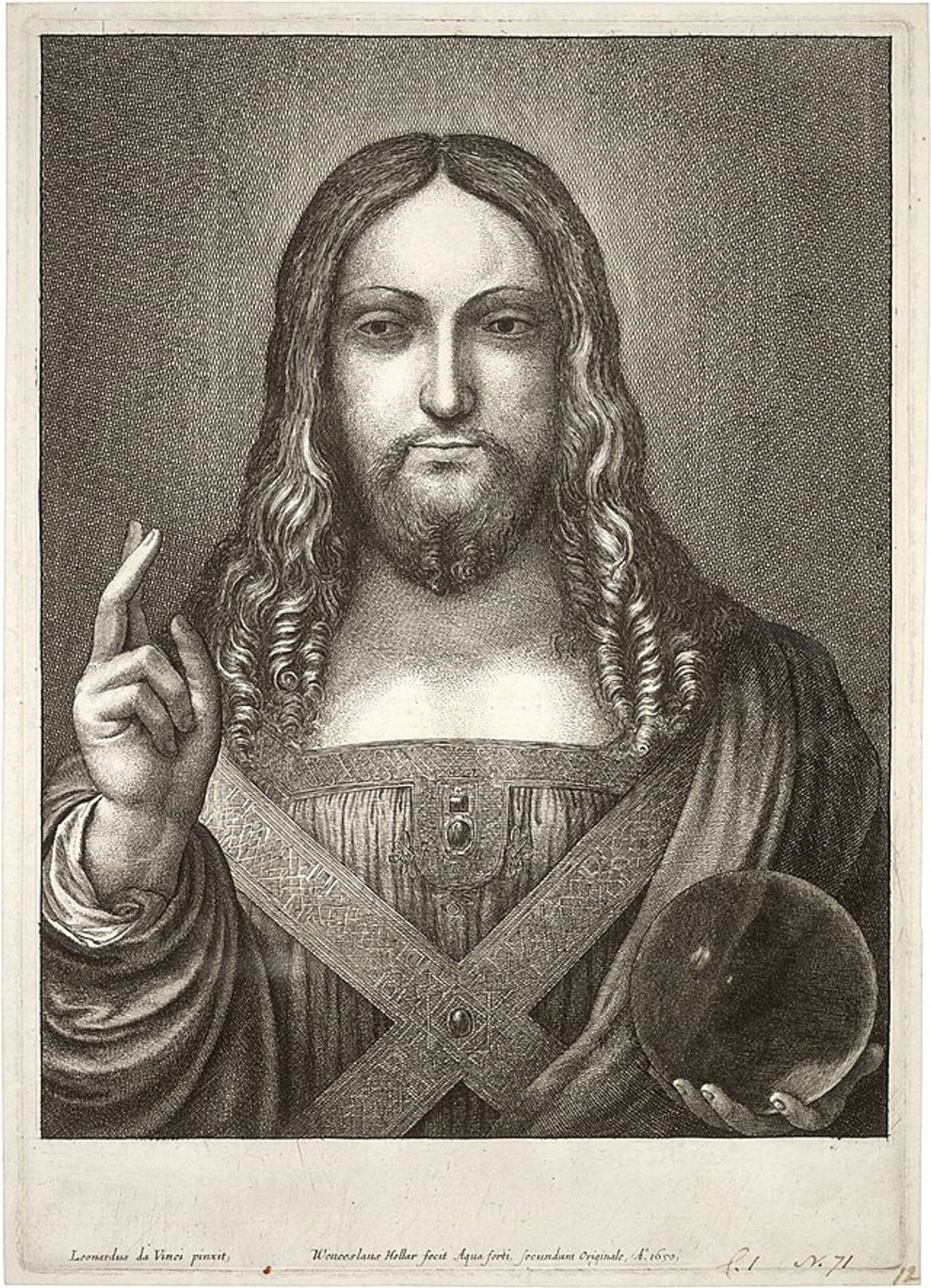

Wood and Dalivalle have also discussed other possible hypotheses. One is the crucial role played by an etching of Leonardo’s Salvator Mundi made by the Royalist Wenceslaus Hollar—then living in exile in Antwerp—which is inscribed (in Latin): “Leonardo painted it” and Hollar etched it “from the original” in 1650. After James Hamilton’s execution in 1649, his brother, the 2nd Duke, transported a large portion of his collection to the Netherlands to be sold. Could Hamilton’s Salvator Mundi have been part of this consignment, and could this explain the “how and the why” Hollar etched it “from the original” in Antwerp at that precise time? (Indeed, in 1649 and 1650, Hollar made a number of etchings after Italian paintings that were available to him in the original.)

Wenceslaus Hollar claimed to have etched the Salvator Mundi “from the original” while he was in exile in Antwerp Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, Toronto

There is even an intriguing possible piece of evidence to support this: in a shipping crate containing Hamilton’s pictures there was a “Christ holding up his two fingers”, but without an attribution. The shortage of other candidates in the Hamilton collection, Wood believes, makes this at least an avenue worth exploring.

Dalivalle places this hypothesis among the “red herrings” that will be fully addressed in the forthcoming book Leonardo’s Salvator Mundi and the Collecting of Leonardo in the Stuart Courts, co-authored by Dalivalle, the US art dealer Robert Simon and the Leonardo expert Martin Kemp (Oxford University Press)—much-delayed and now due for publication next year.

As of now, it is impossible to determine whether Hamilton’s Salvator Mundi is also the Salvator Mundi now in Louvre Abu Dhabi—so the hunt is on. The writer Ben Lewis, who alerted The Art Newspaper to Woods’s discovery, is also producing a publication on the Salvator Mundi (Ballantine/HarperCollins, 2019), and believes that Wood’s research will “significantly change the direction of his book”.

Experts will now be scrutinising Hamilton’s collecting habits and asking whether any credible Leonardos—rather than works by his pupils—have emerged from the Venetian collectors and dealers he bought from. They will also be researching the works that Hamilton inherited from his forebears.

Regarding the subsequent history of Hamilton’s Salvator Mundi, there are two alternatives at issue. One allows Hamilton’s “Christ: with a Globe in his hande” to pass to Charles I around 1640. The other allows Hamilton’s picture to go to the Netherlands in 1649. Hopefully all the pieces will fall into place in time for the Louvre’s Leonardo exhibition in Paris next year (from 24 October 2019), when the painting will be further researched and catalogued.