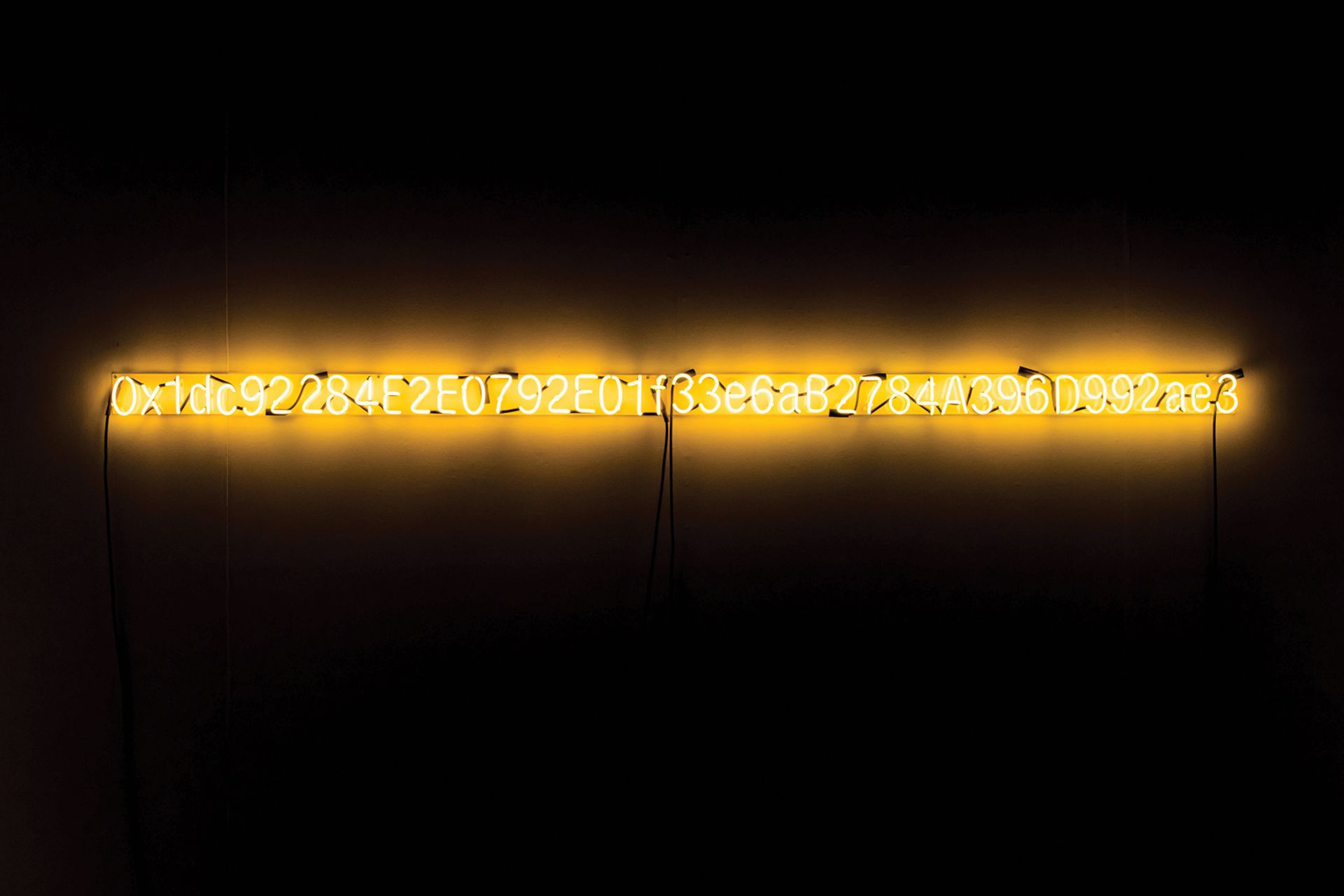

Kevin Abosch and Ai Weiwei have collaborated on creating unique blockchain addresses as proxies for “priceless moments” both artists have shared, with each address validated by a fraction of a Priceless token, which is divisible (and therefore discretely sellable) to 18 decimal places Courtesy of the artists

A gold rush, a bubble, irrational exuberance—or the Holy Grail? Such are the more extreme descriptions of blockchain, which in the past year has gone from being arcane tech-speak to common parlance. It is increasingly touted as a digital revolution by manifold technology startups in fields as varied as real estate, music, diamonds, insurance, marine archaeology and, yes, art. Wired magazine recently published an article titled 187 Things the Blockchain is Supposed to Fix, which listed cancer, climate change and even paper.

In July, Christie’s partnered with Vastari, an online company facilitating exhibition loans and tours, to stage an art and tech summit in London. Called Exploring Blockchain, it was just the first of a promised series looking at new technologies that are impacting the art world.

Put simply, blockchain, or distributed ledger technology (DLT), was originally developed to record transactions in cryptocurrencies such as bitcoin. Transaction information is not stored in one place, but embedded in digital code on shared databases and protected from deletion, tampering and revision. This method of entering and storing information in a database in a way that cannot be changed or corrupted has many potential applications in the art market, and there are now a startling number of hopefuls operating using blockchain.

There are countless blockchains, many of which are private, and one issue is their lack of interconnectivity. DLT is still a nascent technology and the question is whether a few players will finish by dominating the market as has already happened with bitcoin.

Abosch recently sold another digitally inspired work, Yellow Lambo (2018)—a neon sculpture of a blockchain address for a Lamborghini—for $400,000: more than the price of the actual car Yellow Lambo: courtesy of the artist

Myriad incarnations

Making sense of all these initiatives is challenging but there are various business models harnessing blockchain in the art field. Most make use of the Ethereum blockchain platform—a much cheaper approach than building their own solution.

The first model is art registries, which is where the technology offers incontestable benefits. All the information about a work of art is entered on the chain, so ownership of the work can be tracked and its characteristics recorded in a form that cannot be modified. This is potentially good for verification of authenticity, provenance and trust. It may have particular benefit for living artists, allowing them to track sales and eventually claim resale rights.

Companies such as Artory, Verisart and Codex offer registration and certificates for art. The information entered into the blockchain must be correct, making it most suitable for works by living artists.

For art transactions, Codex has partnerships with around 5,000 auction houses, all of which are registered on its blockchain. The auction house Paddle8 has also partnered with its owner The Native, a Swiss tech firm, to offer a P8Pass for buyers, certifying their purchases on the blockchain, which boosts trust.

Artory has a vetted list of specialists who verify the information that goes into the blockchain. Codex and Verisart do not have this restriction, occasionally with farcical consequences. In June, the tech personality Terence Eden registered himself as the owner of Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa on Verisart’s network, and was sent a certificate to prove it. Obviously, Eden is not the owner and, as Verisart points out, the timestamp alone proves that. But this does highlight a problem in the system—as Nanne Dekking of Artory said at the Christie’s summit, “garbage in, garbage out” (although he used a more indelicate term).

The problem of linking a physical object to its blockchain record is an issue and a number of operators are trying to offer solutions. They include Veracity Protocol (formerly Value Protocol), Dust Identity and Tagsmart, which stamps the back of a work of art, then glues a QR code over the top to create a “tag”. A certificate and digital passport are then issued, which can be put on the blockchain.

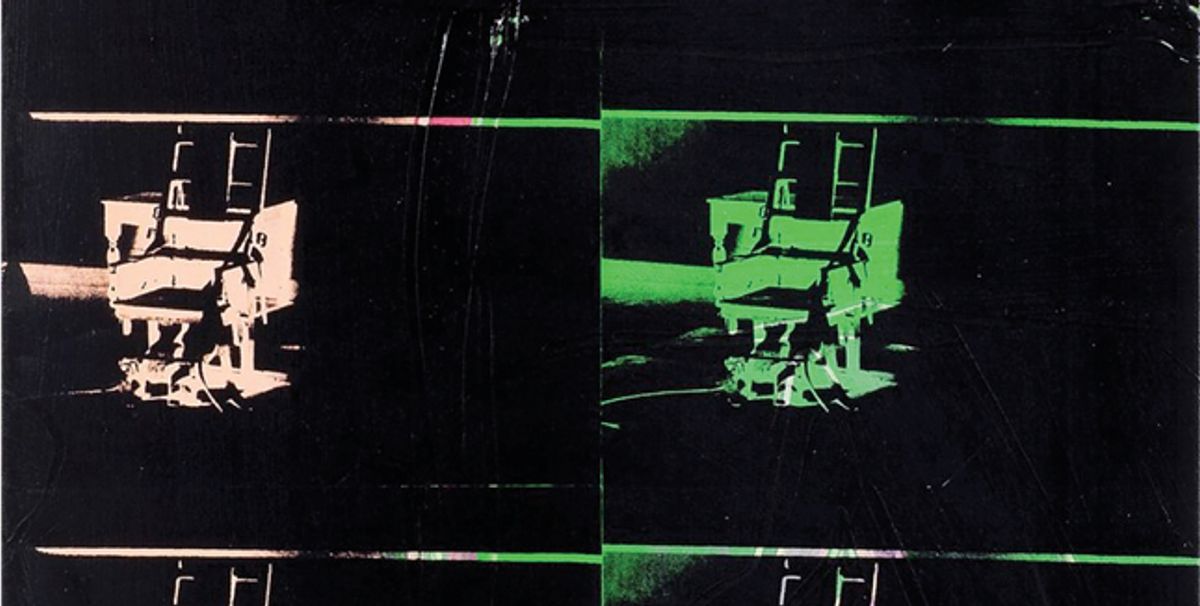

Some companies use blockchain for trading digital art, which can vary from CryptoPunks (10,000 unique pixel art characters), CryptoKitties (digital cats) and Dada.NYC (a social networking platform where people speak to each other through drawings) to an editioned work of crypto-art, The Forever Rose, which sold for the equivalent of $1m in cryptocurrency, although it is only a piece of code with no physical manifestation, according to Kevin Abosch, the Irish conceptual artist who created it. Abosch has recently launched a crypto-art project with Ai Weiwei called What is Priceless? using blockchain addresses as (tokenised) proxies for “priceless moments” the pair have shared.

John Zettler of the Rare network, which specialises in digital art, says: “Before, anyone could replicate and redistribute a digital file… But registering works on the blockchain brings permanence and proof of ownership, thus enabling a secondary market.”

Fractional ownership

However, the most active and experimental area has been in investment in art—notably fractional ownership or tokenisation, allowing individuals to buy a small share of a work of art and trade it. The most high-profile player is Maecenas, but many others operate comparable schemes.

Maecenas’s message is clear—it is “not for art lovers, but for investors”; the art never leaves a freeport or secure warehouse. At the time of writing, the site was offering shares in Warhol’s 14 Small Electric Chairs (1980), which is 51% owned by Dadiani Syndicate (based in Mayfair, London), a partner of Maecenas. According to Maecenas’s co-founder Marcelo Garcia Casil, the offer has been oversubscribed. The firm also offers loans to galleries and collectors who pledge their art as collateral. Maecenas and other startups, such as Look Lateral, take payment in tokens (cryptocurrencies, mostly their own). Maecenas has Art, Look Lateral has Look, and so on.

The firms raise money through initial coin offerings (ICOs), with investors pledging to buy tokens with fiat (currency defined by a government as legal tender) or cryptocurrencies such as bitcoin. This is a similar model to crowdfunding, and as Anton Ruddenklau, the co-leader of financial technology at KPMG International, said at Christie’s: “It’s essentially free money.”

There is a lot of hype around these startups, which eagerly cite various figures for the total value of the art and collectibles market—everything from $1.6 trillion (Codex) to a hair-raising $4 trillion (Tilburg University). The figures help entrepreneurs sell the idea of unlocking market potential by monetising it. Not everyone subscribes to their view. At the Christie’s conference, Zettler said: “Anyone who wants to tokenise physical art is going to fail.”

Clearly, there will always be a risk with startups creating their own currencies. There are over 1,000 cryptocurrencies in existence but, according to a recent article, more than 800 of them are now worthless.

So, Holy Grail or snake oil? The answer lies somewhere in between. Blockchain could improve many aspects of the art market by offering a secure database of information about provenance, authenticity and ownership. Various levels of access through “keys” can ensure privacy—an important consideration for the art market.

In a utopian presentation at Christie’s, the photography specialist Anne Bracegirdle envisaged a world where all information about works of art—their provenance, transactions, prices and owners—could be held on a single shared blockchain across the industry, from galleries and curators to collectors, advisers and auction houses. The resulting savings in administration costs could be mind-boggling.

Utopia or the future? Only time will tell.

Blockchain: the main players at a glance

Artory Founded in 2016 by Nanne Dekking with $7m raised partly from Hasso Plattner, the art collector and founder of software supplier SAP. Artory registers information about works of art from “vetted partners”.

Codex Founded in 2017 by Mark Lurie and Jess Houlgrave, it has raised $10m. Stores information about high-value assets such as art, wine and watches. Has its own cryptocurrency, CodexCoin, to pay for services. A network of partners offer art-related services, from fractional ownership to insurance, appraisals, financing and art-marking technology.

Look Lateral Founded in 2017 by Niccolò Savoia, this is the technology behind Fimart (Fractional Marketplace of Art). Sales are recorded on Dragonchain blockchain, and paid for with Look tokens.

Maecenas Founded in 2016 by Marcelo Garcia Casil, Miguel Neumann and Federico Cardoso, it has raised $15.5m and offers investment in art via fractional ownership, bought with ART tokens, its own cryptocurrency. A single work, Andy Warhol’s 14 Small Electric Chairs (1980), valued at $5.6m, is being offered for investment via an auction, which closes on 5 September. It belongs to Maecenas partner Dadiani Syndicate, which is auctioning 49% of the work.

Paddle8 Founded in 2011 by Alexander Gilkes, Aditya Julka and Osman Khan. After near-death in 2017 with the bankruptcy of its parent company, Auctionata, Paddle8 is now owned by the tech company The Native and offers bitcoin certification of works of art. Also partners with Verisart.

RARE Founded in 2017 by John Zettler, Kevin Trinh and Matthew Russo, Rare tokenises digital art and puts it on blockchain, enabling a secondary market in digital art, the founders say.

Verisart Founded in 2015 by Robert Norton with $500,000 funding from investors including Shepard Fairey, the American artist, and The Native, a Swiss technology company founded by Izabela Depczyk, the former chief executive of ArtNews. Verisart issues certificates of authenticity for works of art, initially for those created by living artists, but in a second phase for older works too. Partners include Paddle8.

• Blockchain: how the revolutionary technology behind Bitcoin could change the art market