Issues of provenance, copyright and authentication may soon become a thing of the past, if a potentially revolutionary technology is adopted as quickly by the art world as it has been by the financial sector. And it is not just Silicon Valley hype; art start-ups are already finding real-world applications for blockchain, the technology behind the cryptocurrency Bitcoin. While Bitcoin has recently had its struggles with internal disputes and a reputation for enabling drug deals, blockchain is emerging as the software with the most significant impact.

Highly secure

A blockchain essentially acts as a public database on which transactions are permanently recorded. It is also highly secure: when a transaction occurs, instead of being recorded on a single, centralised ledger, it instantly appears on a vast network of computers. Although public, it can only be used with a specific “key”. When accessed, an immutable trail is left behind. In other words, blockchain technology eliminates the need for a trusted third party to verify that a transaction has taken place.

The financial sector—from major banks such as UBS and Deutsche Bank to the Nasdaq stock exchange—has been quick to adopt the nascent technology, largely for its capacity to radically drop transaction costs. But other sectors are seeing the potential too. “Every aspect of our economy is adopting certain parts of blockchain and is looking at how to use it,” says Judith Pearson, the president of the Breckenridge Private Asset Management Group and the co-founder of Aris, a leading art title insurer.

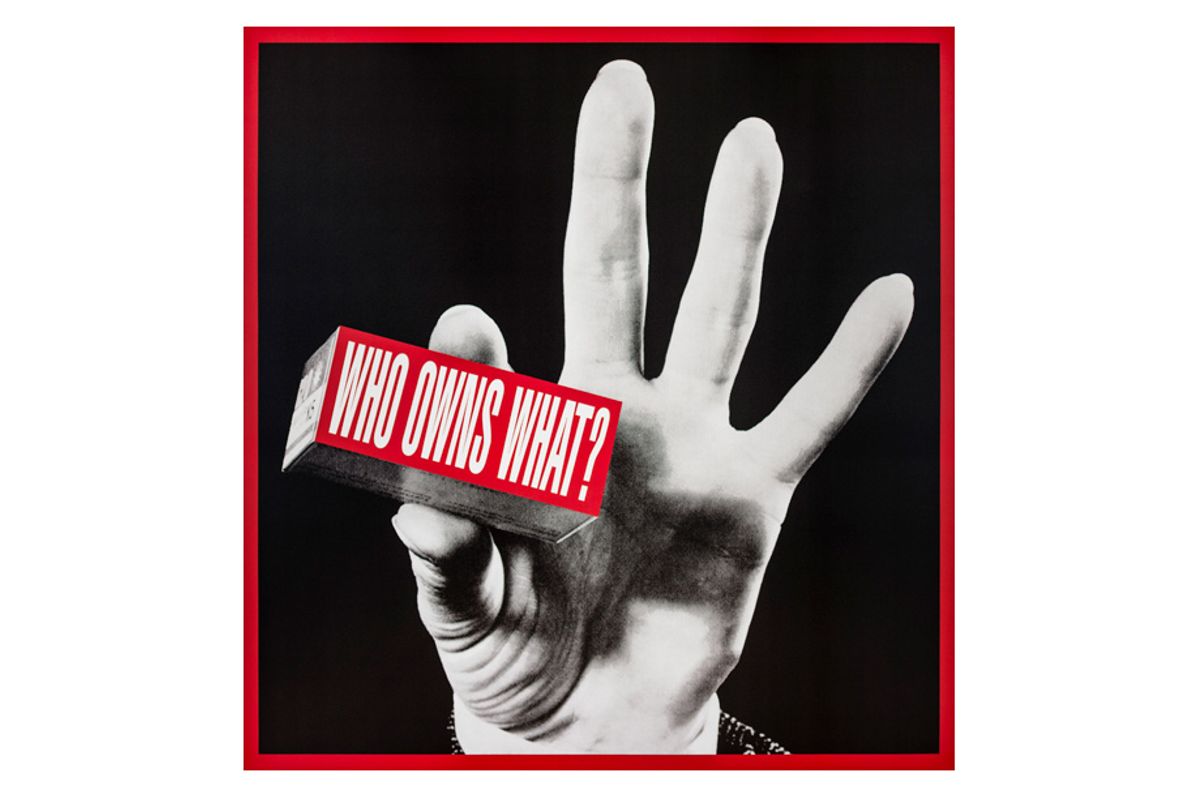

In the art world, blockchain technology may hold the key to overcoming one of its greatest challenges: the lack of transparency. Frequently described as the last unregulated market, the art world often operates on trust alone. But this trust keeps being tested, as recent forgery scandals such as the Knoedler Gallery fiasco and the case of German forger Wolfgang Beltracchi show.

“The art market has flourished because of the lack of transactional standards and transparency,” Pearson says. A networked digital ledger such as a blockchain could help keep track of a work of art’s movements without relying on a paper-based—and at times insecure—system of recording provenance. But this would require the trade to adopt the new technology, which it may be slow to do.

Leading the way

Unsurprisingly, the first forays into the art trade’s use of blockchain have been made by start-ups. Ascribe, for example, offers artists a platform for uploading their digital works, securing their attribution and selling them. Masha McConaghy, the co-founder of Ascribe and a former curator, says that the company’s aim is to overcome the hurdles of collecting digital art. “The value of a work is based on its provenance, but how do you track the provenance of a digital work that can be copied for free, millions of times, and spread throughout the world?” Ascribe, which she describes as “potentially game-changing”, is currently being used by more than 5,000 artists and “dozens of organisations” (in 2015, the Museum of Applied Arts in Vienna acquired several editions by the artist Harm van den Dorpel that had been authenticated by Ascribe).

Access to all

Meanwhile, the Silicon Valley-based start-up Blockai is trying to democratise access to copyright protection. The platform allows artists to claim copyright on their work instantaneously and shows them where it is being used. Blockai also acts as a fraud deterrent. “If someone tries to claim somebody else’s work, there will be a permanent record that you can’t put through a paper shredder or hit delete on,” says Nathan Lands, Blockai’s chief executive officer.

Other art-related blockchain companies include Verisart, founded by Robert Norton, the former chief executive officer of Sedition and Saatchi Online, which assigns certificates of authenticity to works of art. Norton and McConaghy are participating in a panel discussion at the Frankfurt Book Fair on 19 October titled Blockchain, Bitcoin & Co: the New Currencies of the Arts. The art pricing database Artprice also launched a blockchain project in May.

Getting physical

Digital art, however, only makes up a small proportion of the art market. The real coup would be to bridge the gap between physical art and blockchain. George McDonaugh, a blockchain entrepreneur, offers a solution by combining it with tagging technology.

Together with his wife, a fine art restorer, and a company called Norman Ventures, McDonaugh created a prototype for a “chainmark”: a chaotic mixture of different-coloured materials that can be placed on the side of a painting. This produces a unique fingerprint that can then be “hashed” onto a blockchain. A missing chainmark could reveal that a work has been tampered with. Alternatively, fresh canvases could also be tagged with a chainmark. “Imagine you’re a young art student and you go onto Amazon to buy a canvas. You could have the choice between a blockchainable canvas that attributes it to you forever, or just a regular one.”

For all the excitement the new technology is generating, many believe that the dangers of running a decentralised ledger are not fully understood. Keen to educate the art world about blockchain technology, Ruth Catlow, an artist and co-founder of the London-based art organisation Furtherfield, and Ben Vickers, the curator of digital at London’s Serpentine Galleries, organised a conference in the UK capital in March, bringing together leading figures from the worlds of technology and cultural policy. Vickers says: “We organised [the conference] because we’re quite worried about blockchain. Technologies have a tendency towards shaping reality in ways that people don’t perceive. Blockchain is particularly terrifying because it has such profound implications for governance, identity and global supply chains.” Last year, Furtherfield staged the exhibition The Human Face of Cryptoeconomies. It is also organising regular workshops on the topic, has released a film titled Change Everything For Ever and is due to publish a related book that will be uploaded onto a blockchain.

Artists are finding ways of cutting through some of the incomprehensible language around blockchain technology and making the topic visually engaging. The New Zealand artist Simon Denny, whose exhibition Blockchain Future States opened at New York’s Petzel Gallery this month (until 22 October), has used the game Risk to illustrate the technology. The show, which is a sequel to his display at the Berlin Biennale, looks at three major blockchain companies through the lens of the world-conquering board game. Despite the militaristic undertones, Denny sees the technology as a positive force that offers an “interesting proposition” for dealing with the general sense of dissatisfaction resulting from the effects of globalisation. He says: “Instead of retreating back to nationalism and hunkering down behind a wall, [through blockchain and Bitcoin] there’s an attempt at a fairer global spread. It at least has a utopian bent to it.”

Whether the mainstream art world embraces blockchain technology remains to be seen. Pearson says: “I have advised several companies with business plans that could benefit from blockchain technology and have made introductions, but they haven’t moved forward yet. The operative word here is ‘yet’.”

Perhaps tomorrow’s Peter Doigs will be able to prove what work is theirs through a few clicks instead of a three-year legal battle.