Art Basel is this year opening its doors to blockchain, the revolutionary technology behind cryptocurrencies such as bitcoin and ether.

Art Basel’s Conversations programme includes Blockchain and the Art World, a group discussion on 14 June that features the leading digital artist Simon Denny, among others. On 13 June, a conference called Basel ArtTech+Blockchain Connect, organised by the New Art Academy with Forbes, is taking place at Messe Basel.

Much of the focus on blockchain’s application within the cultural sphere has focused on its role in markets—it is, after all, fundamentally a financial creation. Ruth Catlow, the co-director of the London-based art and technology organisation Furtherfield, is one of the authors of a new book, Artists Re:Thinking the Blockchain (Torque Editions and Furtherfield). In her introduction, she writes that “one of the most important and hard-to-grasp characteristics of the blockchain is the way it puts finance, or its mechanisms, at the heart of every action in the digital domain”.

One might surmise that artists would therefore find it uninspiring—but no. Rob Myers, one of the early adopters of blockchain as an artistic tool, has written: “The ideology and technology of the blockchain and the materials of art history—especially the history of conceptual art—can provide useful resources for mutual experiment and technique.”

Catlow says that the area of blockchain she finds particularly fascinating is “artists as crypto- financiers”. She explains: “Blockchain has arisen at the same time as art has become a certain kind of asset class. And these things are emerging at the same time, so we’re seeing artists who are thinking very carefully about capital, about art and the way it relates to people as a commodity and as a financial entity.”

Blockchain has arisen as art has become a certain kind of asset class

Ben Vickers, the chief technology officer at the Serpentine Galleries in London, has noted a curious development as artists have engaged more deeply with blockchain. “Artists who were previously thinking through almost utopian ideas or different organising structures as part of their practice have got mixed up in the blockchain space, and then suddenly, they’ve found themselves migrating away from the art world. They’re now participating in this emergent blockchain economy and are producing companies but working with an artistic toolset.” Vickers says that Berlin is “a major hub” for this kind of activity.

In the US, meanwhile, Catlow recently saw the extreme ways in which artists are engaging with blockchain transactions. “What is huge, but what I feel far less sanguine about, are things like the ‘digital collectibles’—cryptopunks, rarepepes. These are being talked about as art in New York and being traded and sold.” At the Ethereal Summit, the arts and culture event run by the blockchain company Ethereum, Catlow witnessed a cryptokitty—a “scarce digital image of a cat”—being sold in an auction for $140,000.

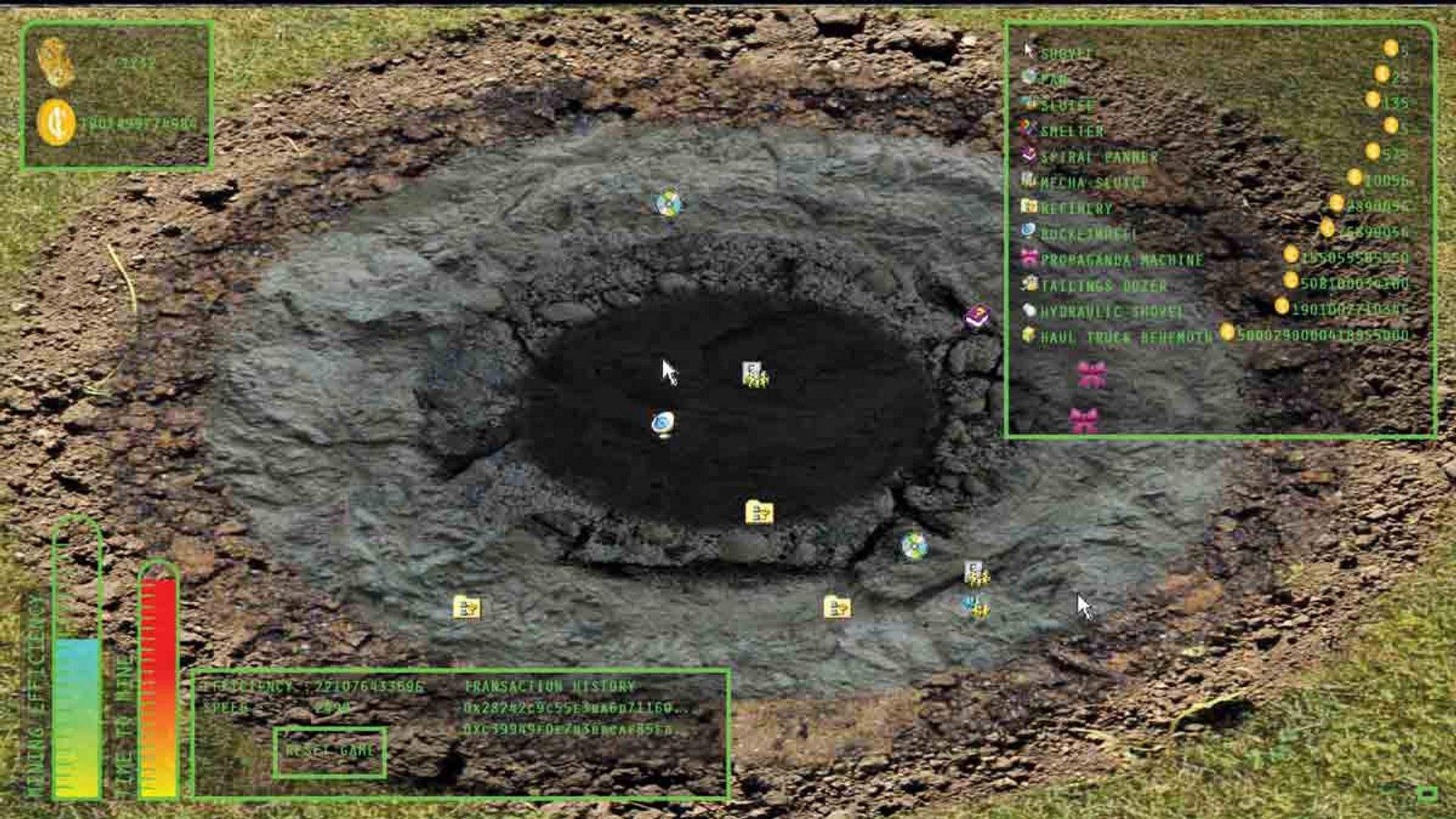

Sarah Friend’s Clickmine (2017) satirises clicking games

Despite the fact that “the tools and infrastructure are at a very early stage”, Catlow says, “we’re certainly seeing some very strong conceptual artworks coming out of this space that are using blockchain as a medium.” Drawing comparison with Net Art, the movement that developed in the early days of the internet, she estimates that we are “in about 1992”—in other words, the earliest stages. But the comparison with online art is instructive. Vickers, like many involved in internet culture, describes himself as a “recovering cyber-utopian”. They saw the internet’s early promise of a decentralised, transparent, democratic space invaded by corporations and mass surveillance, and Catlow and Vickers marry a qualified optimism about blockchain’s possibilities to a distinct awareness of its potential pitfalls.

“This is where the attractive rhetoric [of blockchain] for me has always sat: that you could have people co-ordinating the use of resources that matter to them around the world in a more co-operative way,” Catlow says. “But I’m more cautious than I was, because that was what the web was supposed to be about, too.”

Blockchain hitesh-choudhary

WHAT IS BLOCKCHAIN?

A blockchain acts as a public database in which transactions are permanently recorded. It is also highly secure: when a transaction occurs, instead of being recorded on a single, centralised ledger, it instantly appears on a vast network of computers. Although public, it can only be used with a specific “key”, and when it is accessed, an immutable trail is left behind. In other words, blockchain technology eliminates the need for a trusted third party to verify that a transaction has taken place. The financial sector, from banks such as UBS and Deutsche Bank to the Nasdaq stock exchange, has been quick to adopt the nascent technology, largely for its capacity to radically reduce transaction costs. But other sectors are seeing its potential, too. Blockchain technology may hold the key to overcoming one of the art world’s greatest challenges: a lack of transparency. A networked digital ledger such as a blockchain could help to keep track of a work of art’s movements without relying on a paper-based—and at times insecure—system of recording provenance. But this would require the trade to adopt the new technology, which it may be slow to do. J.Mi.

Primavera De Filippi’s Plantoid (2016) josephparis.fr

Five artists using blockchain

Primavera de Filippi

Filippi is the creator of Plantoid, which Catlow describes as “an android plant that dances and glows when you tip it with bitcoin or ether; it then commissions an artist to make its babies”. The work “has this idea of a kind of evolutionary capital built into it, in a way that I think is a really useful way to think about one form of blockchain art”, Catlow says. Filippi admits that she is only a part-time artist, because she is a leading academic in the field of decentralised technologies such as blockchain, teaching at Harvard, among other prominent universities.

Ed Fornieles

Few artists mine digital technologies and the online space as smartly as Fornieles. He has now entered blockchain, with the imminent launch of The Crypto Certificate, which will enable investors to help Fornieles raise funds for his new work, in exchange for future profits. The work is both an exploration of the language and mechanisms of blockchain and a new form of connection between visual artist and audience, enabling people “to benefit from his practice over time as a result of participation”, Vickers says.

Rob Myers

Myers has explored blockchain in a number of works that might be “narrative and, frankly, very funny”, Catlow says, or “more technical, much more in line with 1970s conceptualism”. Perhaps most striking is Facecoin, which explores how cryptocurrencies rely on a “proof of work” system to prevent abuse. Facecoin uses bitcoin hashes—the strings of 64 letters and numbers produced every time a transaction is made—to produce greyscale grids and then uses a face-detection algorithm to look for faces in the grids. In finding the faces, the machine is an artist—and the “portraits” it creates are “proofs of aesthetic work”, Myers says.

Jonas Lund

In the work Jonas Lund Token, the Swedish artist created 100,000 shares in his artistic practice, with each share equalling one Jonas Lund Token (JLT), a cryptocurrency he created on the Ethereum blockchain. Shareholders can shape how Lund’s artistic practice develops. The shares are distributed in different ways, such as the purchase of physical works Lund makes and through a “bounty programme”, in which shares are exchanged for actions relating to Lund’s practice, such as giving him a solo exhibition. “He incentivises his own networked effect in the art world,” Vickers says.

Sarah Friend

An artist and software engineer particularly focused on the development of games, Friend developed Clickmine, a work co-commissioned by Furtherfield and the Neon Digital Arts Festival, last year. A kind of satire, it moves the frenetic absurdity of clicking games on to blockchain, where a “hyperinflationary” ERC-20 token, a form of meta-currency, is minted through the game. Furtherfield described it as a “a hypercapitalist frenzy that makes the generation of useless wealth via clicking more literal than ever before”. B.L.