“I wanted to break the notion that blackness was a reductive condition, that it couldn’t be complex and chromatic,” says the 62-year-old artist Kerry James Marshall of his work Invisible Man (1986), now on display at the Rennie Collection in Vancouver. “This colour here,” he says, pointing to the edge of the work, “is actually a very deep green”.

The enigmatic figure in Invisible Man, mostly made out by the whites of his eyes and his toothy grin, seems either to emerge from or disappear into the background, and is at once skeletal and defiant, frightening and mocking. The work was inspired, Marshall says, by a 1961 horror film called Sardonicus, directed by William Castle, in which a man’s face becomes frozen in a contorted grimace when he robs his father’s grave to get a winning lottery ticket. The painting speaks to Marshall’s familiar themes of absence and presence, visibility and invisibility. “It’s our Mona Lisa,” says Bob Rennie, the Canadian real estate magnate and collector who bought the work for $53,775 at an auction in Los Angeles in 2006, from the estate of the African-American actor Paul Winfield.

It is one 33 objects in the show Kerry James Marshall: Collected Works (2 June-3 November), including sculptures, drawings and paintings spanning 32 years of the artist’s career, from La Venus Negra (1992) to the Garden Party (2004-13), all owned by Rennie, the biggest single collector of Marshall’s work. The retrospective opens just a couple of weeks after Marshall set the auction record for the highest price paid for a work by a living African American artist, when the rapper and producer Sean Combs bought his Past Times (1997) for $21.1m at Sotheby’s in New York.

This is probably the first instance in the history of the art world, where a Black person took part in a capital competition and won.

“The import of that is missed on a lot of people,” Marshall says, of Combs’s acquisition. “This is probably the first instance in the history of the art world, where a Black person took part in a capital competition and won.” Marshall says the community of African American collectors is growing. “It’s becoming the case that people have more disposable resources that they can apply to buying things like art work,” he says, adding: “But if you think about the history of art—where were Black people when [capitalism and markets were forming] 500, 600 years ago? Black people in the Western hemisphere—from 1865 until now, that’s less than 200 years out from being considered chattel property, being bought and sold themselves.”

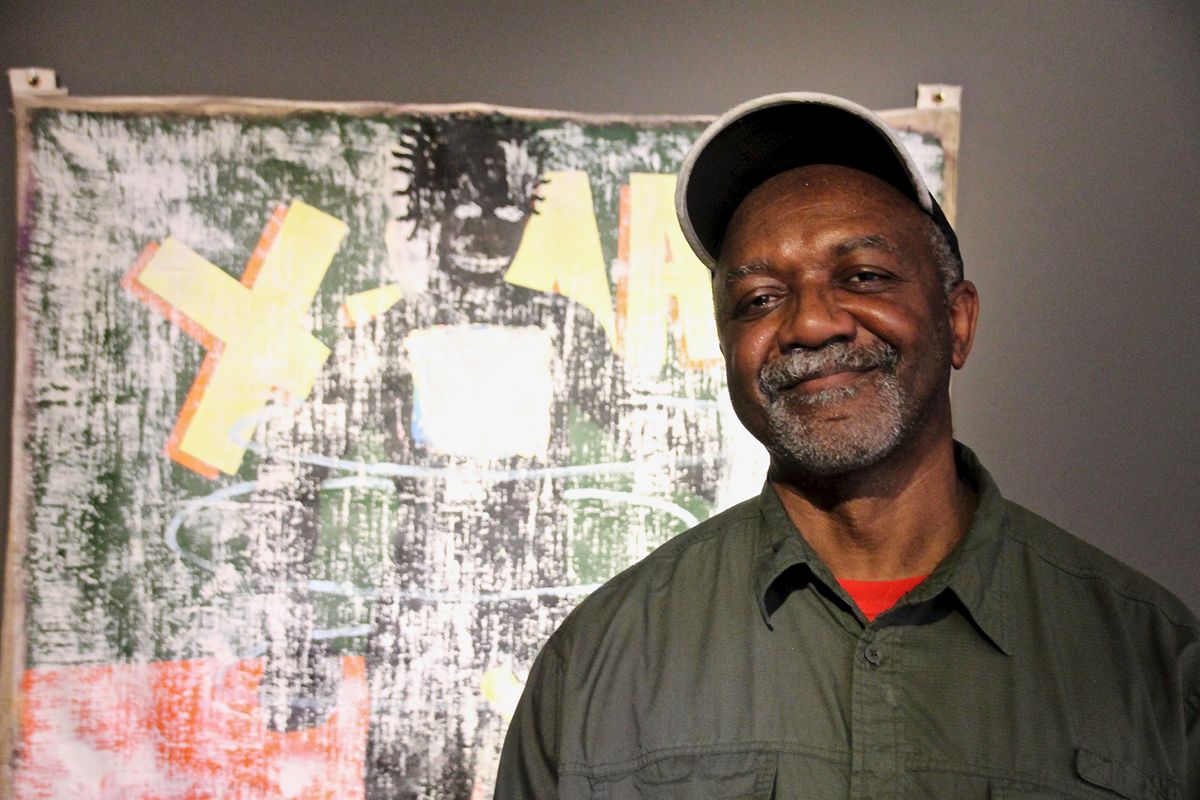

This view of a larger historic context can also be seen in the work X-Man (1989), which Marshall says is not based on the Marvel comic book series but rather inspired by “the way Nation of Islam [leaders] dropped their slave name and adopted the X as an unknown quantity”. His interest in the comic book genre also fuses with his exploration of African mythology and culture in his long-running Rythm Mastr series, with the next segment to be revealed at the Carnegie International in October.

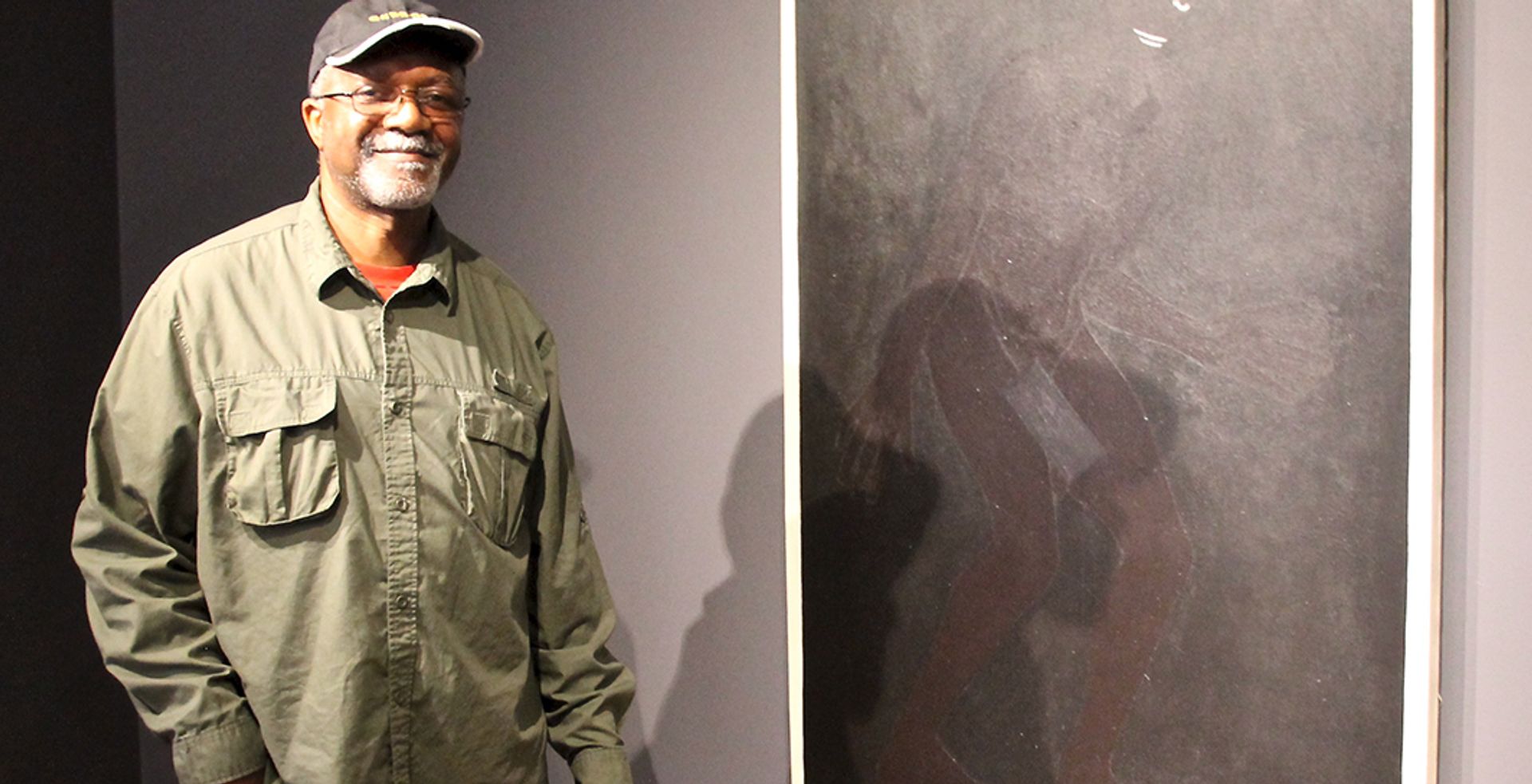

Kerry James Marshall with Invisible Man (1986) Hadani Ditmars

When asked if he feels any particular urgency in his work considering the current political climate, Marshall replies that “Trump is part of a continuum”, and that America and the forces that created it “won’t change in our lifetime”.

And how will Marshall’s work resonate in Vancouver, a city with a tiny Black community? Standing near his sailboat sculpture Wake–at once a shrine to the victims of slavery and a tribute to the ensuing generations—the artist does not mince words. “Canada is part of the settler tradition,” he says, that occupied indigenous land.

Rennie, who also collects the work of Canadian First Nations artists like Brian Jungen as well as the Palestinian artist Mona Hatoum, sees a common thread. Standing next to Marshall’s series of giant stamps featuring Civil Rights Era phrases like “Black is Beautiful” and “We Shall Overcome”, Rennie says: “In Canada we don’t have a defensive mechanism in terms of black and white race issues the way it exists in America. But the artists we collect share a similar fight about race and identity and not being seen.”